- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 25

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 25

“Oh, very much!”

“There, that’s better! ... You’re better now, are you not? ... And what a funny house, isn’t it, with landscapes like that in it?”

“Yes, it’s like the Musee Greviny ... But, I say, Erik ... there are no tortures in there! ... What a fright you gave me!”

“Why ... as there is no one there?”

“Did you design that room? It’s very handsome. You’re a great artist, Erik.”

“Yes, a great artist, in my own line.”

“But tell me, Erik, why did you call that room the torture-chamber?”

“Oh, it’s very simple. First of all, what did you see?”

“I saw a forest.”

“And what is in a forest?”

“Trees.”

“And what is in a tree?”

“Birds.”

“Did you see any birds?”

“No, I did not see any birds.”

“Well, what did you see? Think! You saw branches! And what are the branches?” asked the terrible voice. “There’s a gibbet!z That is why I call my wood the torture-chamber! ... You see, it’s all a joke. I never express myself like other people. But I am very tired of it! ... I’m sick and tired of having a forest and a torture-chamber in my house and of living like a mountebank, in a house with a false bottom! ... I’m tired of it! I want to have a nice, quiet flat, with ordinary doors and windows and a wife inside it, like anybody else! A wife whom I could love and take out on Sundays and keep amused on week-days ... Here, shall I show you some card-tricks? That will help us to pass a few minutes, while waiting for eleven o’clock tomorrow evening ... My dear little Christine! ... Are you listening to me? ... Tell me you love me! ... No, you don’t love me ... but no matter, you will! ... Once, you could not look at my mask because you knew what was behind ... And now you don’t mind looking at it and you forget what is behind! ... One can get used to everything ... if one wishes ... Plenty of young people who did not care for each other before marriage have adored each other since! Oh, I don’t know what I am talking about! But you would have lots of fun with me. For instance, I am the greatest ventriloquist that ever lived, I am the first ventriloquistin the world! ... You’re laughing ... Perhaps you don’t believe me? Listen.”

The wretch, who really was the first ventriloquist in the world, was only trying to divert the child’s attention from the torture-chamber; but it was a stupid scheme, for Christine thought of nothing but us! She repeatedly besought him, in the gentlest tones which she could assume:

“Put out the light in the little window! ... Erik, do put out the light in the little window!”

For she saw that this light, which appeared so suddenly and of which the monster had spoken in so threatening a voice, must mean something terrible. One thing must have pacified her for a moment; and that was seeing the two of us, behind the wall, in the midst of that resplendent light, alive and well. But she would certainly have felt much easier if the light had been put out.

Meantime, the other had already begun to play the ventriloquist. He said:

“Here, I raise my mask a little ... Oh, only a little! ... You see my lips, such lips as I have? They’re not moving! ... My mouth is closed—such mouth as I have—and yet you hear my voice ... Where will you have it? In your left ear? In your right ear? In the table? In those little ebony boxes on the mantelpiece? ... Listen, dear, it’s in the little box on the right of the mantelpiece: what does it say? ‘Shall I turn the scorpion?’ ... And now, crack! What does it say in the little box on the left? ‘Shall I turn the grasshopper?’ ... And now, crack! Here it is in the little leather bag ... What does it say? ‘I am the little bag of life and death!’... And now, crack! It is in Carlotta’s throat, in Carlotta’s golden throat, in Carlotta’s crystal throat, as I live! What does it say? It says, ‘It’s, I, Mr. Toad, it’s I singing! I feel without alarm—co-ack... with its melody enwind me—co-ack!’ ... And now, crack! It is on a chair in the ghost’s box and it says, ‘Madame Carlotta is singing tonight to bring the chandelier down!’ ... And now, crack! Aha! Where is Erik’s voice now? Listen, Christine, darling! Listen! It is behind the door of the torture-chamber! Listen! It’s myself in the torture-chamber! And what do I say? I say, ‘Woe to them that have a nose, a real nose, and come to look round the torture-chamber!’ Aha, aha, aha!”

Oh, the ventriloquist’s terrible voice! It was everywhere, everywhere. It passed through the little invisible window, through the walls. It ran around us, between us. Erik was there, speaking to us! We made a movement as though to fling ourselves upon him. But, already, swifter, more fleeting than the voice of the echo, Erik’s voice had leaped back behind the wall!

Soon we heard nothing more at all, for this is what happened:

“Erik! Erik!” said Christine’s voice. “You tire me with your voice. Don’t go on, Erik! Isn’t it very hot here?”

“Oh, yes,” replied Erik’s voice, “the heat is unendurable!” “But what does this mean? ... The wall is really getting quite hot! ... The wall is burning! ...”

“I’ll tell you, Christine, dear: it is because of the forest next door.”

“Well, what has that to do with it? The forest?”

“Why, didn’t you see that it was an African forest?”

And the monster laughed so loudly and hideously that we could no longer distinguish Christine’s supplicating cries! The Vicomte de Chagny shouted and banged against the walls like a madman. I could not restrain him. But we heard nothing except the monster’s laughter, and the monster himself can have heard nothing else. And then there was the sound of a body falling on the floor and being dragged along and a door slammed and then nothing, nothing more around us save the scorching silence of the south in the heart of a tropical forest!

24

“BARRELS! ... BARRELS! ... ANY BARRELS TO SELL?”

THE PERSIAN’S NARRATIVE CONTINUED

I have said that the room in which M. le Vicomte de Chagny and I were imprisoned was a regular hexagon, lined entirely with mirrors. Plenty of these rooms have been seen since, mainly at exhibitions: they are called “palaces of illusion,” or some such name. But the invention belongs entirely to Erik, who built the first room of this kind under my eyes, at the time of the rosy hours of Mazenderan. A decorative object, such as a column, for instance, was placed in one of the corners and immediately produced a hall of a thousand columns; for, thanks to the mirrors, the real room was multiplied by six hexagonal rooms, each of which, in its turn, was multiplied indefinitely. But the little sultana soon tired of this infantile illusion, whereupon Erik altered his invention into a “torture-chamber.” For the architectural motive placed in one corner, he substituted an iron tree. This tree, with its painted leaves, was absolutely true to life and was made of iron so as to resist all the attacks of the “patient” who was locked into the torture-chamber. We shall see how the scene thus obtained was twice altered instantaneously into two successive other scenes, by means of the automatic rotation of the drums or rollers in the corners. These were divided into three sections, fitting into the angles of the mirrors and each supporting a decorative scheme that came into sight as the roller revolved upon its axis.

The walls of this strange room gave the patient nothing to lay hold of, because, apart from the solid decorative object, they were simply furnished with mirrors, thick enough to withstand any onslaught of the victim, who was flung into the chamber empty-handed and barefoot.

There was no furniture. The ceiling was capable of being lit up. An ingenious system of electric heating, which has since been imitated, allowed the temperature of the walls and room to be increased at will.

I am giving all these details of a perfectly natural invention, producing, with a few painted branches, the supernatural illusion of an equatorial forest blazing under the tropical sun, so that no one may doubt the present balance of my brain or feel entitled to say that I am mad or lying or that I take him for a fool.aa

I now return to

the facts where I left them. When the ceiling lit up and the forest became visible around us, the viscount’s stupefaction was immense. That impenetrable forest, with its innumerable trunks and branches, threw him into a terrible state of consternation. He passed his hands over his forehead, as though to drive away a dream; his eyes blinked; and, for a moment, he forgot to listen.

I have already said that the sight of the forest did not surprise me at all; and therefore I listened for the two of us to what was happening next door. Lastly, my attention was especially attracted, not so much to the scene, as to the mirrors that produced it. These mirrors were broken in parts. Yes, they were marked and scratched; they had been “starred,” in spite of their solidity; and this proved to me that the torture-chamber in which we now were had already served a purpose.

Yes, some wretch, whose feet were not bare like those of the victims of the rosy hours of Mazenderan, had certainly fallen into this “mortal illusion” and, mad with rage, had kicked against those mirrors which, nevertheless, continued to reflect his agony. And the branch of the tree on which he had put an end to his own sufferings was arranged in such a way that, beforedying, he had seen, for his last consolation, a thousand men writhing in his company.

Yes, Joseph Buquet had undoubtedly been through all this! Were we to die as he had done? I did not think so, for I knew that we had a few hours before us and that I could employ them to better purpose than Joseph Buquet was able to do. After all, I was thoroughly acquainted with most of Erik’s “tricks,” and now or never was the time to turn my knowledge to account.

To begin with, I gave up every idea of returning to the passage that had brought us to that accursed chamber. I did not trouble about the possibility of working the inside stone that closed the passage; and this for the simple reason that to do so was out of the question. We had dropped from too great a height into the torture-chamber; there was no furniture to help us reach that passage; not even the branch of the iron tree, not even each other’s shoulders were of any avail.

There was only one possible outlet, that opening into the Louis-Philippe room in which Erik and Christine Daaé were. But, though this outlet looked like an ordinary door on Christine’s side, it was absolutely invisible to us. We must therefore try to open it without even knowing where it was.

When I was quite sure that there was no hope for us from Christine Daaé’s side, when I had heard the monster dragging the poor girl from the Louis-Philippe room lest she should interfere with our tortures, I resolved to set to work without delay.

But I had first to calm M. de Chagny, who was already walking about like a madman, uttering incoherent cries. The snatches of conversation which he had caught between Christine and the monster had contributed not a little to drive him beside himself: add to that the shock of the magic forest and the scorching heat which was beginning to make the perspiration stream down his temples and you will have no difficulty in understanding his state of mind. He shouted Christine’s name, brandished his pistol, knocked his forehead against the glass in his endeavours to run down the glades of the illusive forest. In short, the torture was beginning to work its spell upon a brain unprepared for it.

I did my best to induce the poor viscount to listen to reason. I made him touch the mirrors and the iron tree and the branches and explained to him, by optical laws, all the luminous imagery by which we were surrounded and of which we need not allow ourselves to be the victims, like ordinary, ignorant people.

“We are in a room, a little room; that is what you must keep saying to yourself. And we shall leave the room as soon as we have found the door.”

And I promised him that, if he let me act, without disturbing me by shouting and walking up and down, I would discover the trick of the door in less than an hour’s time.

Then he lay flat on the floor, as one does in a wood, and declared that he would wait until I found the door of the forest, as there was nothing better to do! And he added that, from where he was, “the view was splendid!” The torture was working, in spite of all that I had said.

Myself, forgetting the forest, I tackled a glass panel and began to finger it in every direction, hunting for the weak point on which to press in order to turn the door in accordance with Erik’s system of pivots. This weak point might be a mere speck on the glass, no larger than a pea, under which the spring lay hidden. I hunted and hunted. I felt as high as my hands could reach. Erik was about the same height as myself and I thought that he would not have placed the spring higher than suited his stature.

While groping over the successive panels with the greatest care, I endeavoured not to lose a minute, for I was feeling more and more overcome with the heat and we were literally roasting in that blazing forest.

I had been working like this for half an hour and had finished three panels, when, as ill-luck would have it, I turned round on hearing a muttered exclamation from the viscount.

“I am stifling,” he said. “All those mirrors are sending out an infernal heat! Do you think you will find that spring soon? If you are much longer about it, we shall be roasted alive!”

I was not sorry to hear him talk like this. He had not said a word of the forest and I hoped that my companion’s reason would hold out some time longer against the torture. But he added:

“What consoles me is that the monster has given Christine until eleven tomorrow evening. If we can’t get out of here and go to her assistance, at least we shall be dead before her! Then Erik’s mass can serve for all of us!”

And he gulped down a breath of hot air that nearly made him faint.

As I had not the same desperate reasons as M. le Vicomte for accepting death, I returned, after giving him a word of encouragement, to my panel, but I had made the mistake of taking a few steps while speaking and, in the tangle of the illusive forest, I was no longer able to find my panel for certain! I had to begin all over again, at random, feeling, fumbling, groping.

Now the fever laid hold of me in my turn ... for I found nothing, absolutely nothing. In the next room, all was silence. We were quite lost in the forest, without an outlet, a compass, a guide or anything. Oh, I knew what awaited us if nobody came to our aid ... or if I did not find the spring! But, look as I might, I found nothing but branches, beautiful branches that stood straight up before me, or spread gracefully over my head. But they gave no shade. And this was natural enough, as we were in an equatorial forest, with the sun right above our heads, an African forest.

M. de Chagny and I had repeatedly taken off our coats and put them on again, finding at one time that they made us feel still hotter and at another that they protected us against the heat. I was still making a moral resistance, but M. de Chagny seemed to me quite “gone.” He pretended that he had been walking in that forest for three days and nights, without stopping, looking for Christine Daaé! From time to time, he thought he saw her behind the trunk of a tree, or gliding between the branches; and he called to her with words of supplication that brought the tears to my eyes. And then, at last:

“Oh, how thirsty I am!” he cried, in delirious accents.

I too was thirsty. My throat was on fire. And, yet, squatting on the floor, I went on hunting, hunting, hunting for the spring of the invisible door ... especially as it was dangerous to remain in the forest as evening drew nigh. Already the shades of night were beginning to surround us. It had happened very quickly: night falls quickly in tropical countries ... suddenly, with hardly any twilight.

Now night, in the forests of the equator, is always dangerous, particularly when, like ourselves, one has not the materials for a fire to keep off the beasts of prey. I did indeed try for a moment to break off the branches, which I would have lit with my dark lantern, but I knocked myself also against the mirrors and remembered, in time, that we had only images of branches to do with.

The heat did not go with the daylight; on the contrary, it was now still hotter under the blue rays of the moon. I urged the viscount to hold our weapons ready to fire and not to

stray from camp, while I went on looking for my spring.

Suddenly, we heard a lion roaring a few yards away.

“Oh,” whispered the viscount, “he is quite close! ... Don’t you see him? ... There ... through the trees ... in that thicket! ... If he roars again, I will fire! ...”

And the roaring began again, louder than before. And the viscount fired, but I do not think he hit the lion; only, he smashed a mirror, as I perceived the next morning, at day-break. We must have covered a good distance during the night, for we suddenly found ourselves on the edge of the desert, an immense desert of sand, stones and rocks. It was really not worth while leaving the forest to come upon the desert. Tired out, I flung myself down beside the viscount, for I had had enough of looking for springs which I could not find.

I was quite surprised—and I said so to the viscount—that we had encountered no other dangerous animals during the night. Usually, after the lion came the leopard and sometimes the buzz of the tsetse fly. These were easily obtained effects; and I explained to M. de Chagny that Erik imitated the roar of a lion on a long tabour or timbrel, with an ass’s skin at one end. Over this skin he tied a string of catgut, which was fastened at the middle to another similar string passing through the whole length of the tabour. Erik had only to rub this string with a glove smeared with resin and, according to the manner in which he rubbed it, he imitated to perfection the voice of the lion or the leopard, or even the buzzing of the tsetse fly.

The idea that Erik was probably in the room beside us, working his trick, made me suddenly resolve to enter into a parley with him, for we must obviously give up all thought of taking him by surprise. And by this time he must be quite aware who were the occupants of his torture-chamber. I called him: “Erik! Erik!”

I shouted as loudly as I could across the desert, but there was no answer to my voice. All around us lay the silence and the bare immensity of that stony desert. What was to become of us in the midst of that awful solitude?

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

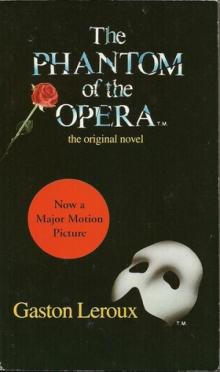

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)