- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Read online

Rouletabille at Krupp’s

by

Gaston Leroux

translated, annotated and introduced by

Brian Stableford

A Black Coat Press Book

Introduction

Rouletabille chez Krupp, here translated as Rouletabille at Krupp’s, was originally published as a seven-part serial in the monthly magazine Je Sais Tout between September 1917 and March 1918, and was reprinted in book form by Pierre Lafitte in 1920. It was the fifth novel featuring Rouletabille that Gaston Leroux had penned, although it became the sixth in volume form because one of the earlier ones was split into two for book publication. It differed from its predecessors, however, in three significant respects, all of which give it a particular historical interest. Firstly, it is the only novel in the series to embody a significant science-fictional component, in its depiction and description of a kind of “ultimate weapon” allegedly so powerful as to potentially capable of putting an end to war. Secondly, it is the only one in which Rouletabille features as a secret agent commissioned by the French government to carry out a covert mission in enemy territory, and it thus became one of the significant pioneering examples of that kind of spy fiction. Thirdly, it is the only novel in the series calculated to serve as morale-building propaganda, and was at least encouraged in its production and publication, if not formally commissioned, by the French Ministry of War.

Publication of fiction in France had, inevitably, been severely impeded by the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, not merely because of the general economic disruption and paper shortages, but because reading fiction—especially fanciful fiction—came to be seen, by the authorities and the public alike, as something essentially frivolous and unbecoming. The kind of reading often described as “escapism,” can seem, at first glance, to be inappropriate in wartime, almost as a kind of “mental desertion” from more serious and purposive concerns. Such fiction as continued to be published in France in 1915 tended to be deadly earnest in its form and concerns, and determinedly naturalistic. The relatively small number of magazines that continued to publish fiction mostly confined their efforts to stories of life in the trenches, blatantly calculated to raise morale by celebrating the everyday heroism of conscripts in the face of routine tribulations. It was not the case that all fiction published in that year was lightly-disguised propaganda, but most of the fiction intended for mass consumption was.

In 1916, however, this situation eased somewhat, and in 1917 it appears to have undergone a definite shift, not with respect to the fundamental propagandistic purposes of the fiction published, but with respect to its narrative strategies. In part, this represented a belated realization that “escapism” is not such a bad thing in wartime, because readers might benefit, even more in peacetime, from a temporary release from the pressures of grim reality, and also a realization that the narrative force of “gripping” fiction can be recruited to the purpose of morale-building in a quasi-inspirational fashion. Kinds of fiction that had become scarce in France in 1915, including action/adventure fiction, historical fiction, crime fiction and science fiction, began to appear in greater quantities again in 1916, usually with a naked propagandistic slant, but also with a much higher priority on entertainment value, and with a much greater imaginative range. After relatively tentative beginnings in that year, there was a noticeable surge in the publication of such works in 1917, although many had obviously been written earlier or separately, and had been hastily adapted to the new regime.

Among the more imaginatively-adventurous novels published in 1917, Félicien Champsaur’s Les Ailes de l’Homme 1had obviously been written as an item of futuristic fiction prior to August 1914 and had had to be awkwardly adapted and augmented; while J. H. Rosny’s L’Enigme de Givreuse 2 simply has an entirely gratuitous chapter in which the protagonist attacks a German submarine dropped into an item of philosophical speculative fiction typical of the author’s work in that vein. Rouletabille chez Krupp, by contrast, was clearly conceived and executed entirely within the new program, with its purposes in mind. It was published in the leading Parisian popular magazine of the day, and warrants consideration as one of the central texts of the morale-boosting project.

If any such fiction was directly commissioned by the Ministry of War, Gaston Leroux would have been at or very near the top of the list of potential conscripts for such war work, as one of the most successful feuilletonistes of the period. Although, like all the other professional writers in France, he had had a very lean time in 1915, when he published no fiction at all, he had resumed duty as a feuilletoniste for the daily Le Matin in 1916, when he had published the 31-part Confitou in January and February and the 135-part La Colonne infernale [The Infernal Column] between April and September. The latter might have been one of the texts prompting the change of official policy, and Le Matin published another 134-part serial, Le Sous-marin “Le Vengeur” [The Submarine Le Vengeur] between September 1917 and February 1918. The early episodes of the latter work were published in parallel with Rouletabille chez Krupp, but the latter must be reckoned the earlier work, even if the production of the serials overlapped, because of the longer publication-lag to which Je Sais Tout was subject.3 Leroux had also published an eight-part serial in Je Sais Tout between June 1916 and January 1917, L’Homme qui revient de loin [The Man Who Came Back from Afar].

Rouletabille chez Krupp was by no means the first French roman scientifique to feature a weapon so dreadful as to be allegedly capable of putting an end to war. Indeed, that notion had been a standard feature of French futuristic speculation since 1840, although standards of dreadfulness had been considerably inflated in the interim, and more pessimistically-inclined writers had began to suspect, if not to take it for granted, that no matter how destructive a weapon might be, military men would be only too keen to use it, even at the cost of the annihilation of civilization, or the entire human species. Given the circumstances of its production, however, Leroux’s novel could not actually depict the deployment of the weapon in question, but had to employ it as an apocalyptic threat whose use against France had to be prevented—a necessity that compelled him to invent, or at least to sophisticate, a formula that was bound to become one of the standard tropes of 20th century spy fiction, which is replete with apocalyptic threats in urgent need of being thwarted by ingenious heroism.

Rouletabille had begun his fictional career as a detective in the tradition of Sherlock Holmes, using the power of logic to solve seemingly-intractable problems—his first adventure, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune (1907)4 remains famous as the first significant “locked room mystery”—but the fundamental narrative purpose of Rouletabille chez Krupp forced the hero into a new mold, as the ultimate prototype of James Bond. Although he still retained his commitment to careful observation and ratiocination, he became a much more proactive protagonist, not merely a solver of mysteries thrown at him by happenstance but an agent provocateur, making things happen and employing his ingenuity to carry out subversive activities under the protection of an assumed identity.

Leroux did not invent spy fiction as such, but in terms of the modern embryology of the genre, he was certainly acquainted with the man who did, who had, like him, worked as a foreign correspondent for a major newspaper in the decade prior to the Great War: the French-born English journalist William le Queux.

Because the Great War had been anticipated for such a long time, and fear of the German war machine had been rife in both England and France ever since its spectacular triumph in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, newspapers in both countries had become very anxious about the possibility that German secret agents might be busy collecting intelligence that might be useful when the war eventually broke

out. Le Queux had played a central role in creating the paranoiac mythology of a German “hidden hand” or “fifth column” devoted to such work, and, in his secondary career as a novelist, had begun to embody the notion in such fictional works as England’s Peril (1899) and The German Spy (1914), as well as such supposedly non-fictional tracts as Spies of the Kaiser (1909). Like Leroux, Le Queux continued producing propagandistic fiction during the war, including fiction about powerful new weapons, such as The Zeppelin Destroyer (1916). His pre-war anxieties had undoubtedly been contagious, although Leroux does not seem to have been infected to any considerable degree until circumstances warranted it, and never wrote the kind of alarmist future war fiction that was Le Queux’s chief stock-in-trade.

Le Queux did not have any conspicuous gift for story-telling, and never acquired the kind of popularity as a fiction-writer that Leroux had in France. His spy stories, moreover—like the vast majority of those produced prior to August 1914—usually featured heroic Englishmen accidentally happening upon and subsequently thwarting the dastardly schemes of German secret agents on an ad hoc basis. The idea that the English or French governments would or should adopt underhanded intelligence-gathering tactics themselves went largely unvoiced in popular fiction until the ethics of necessity came into play.

If Le Queux is unlikely to have had any influence on the French government’s change of policy regarding propaganda fiction, however, one English writer who might well have done so is John Buchan, who wrote one of the war’s surprise best-sellers, The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), while impatiently waiting to be sent on active duty. Although that book follows the already-standardized formula in which an English layman, Richard Hannay, is required by unkind circumstance to thwart insidious German spies, Hannay was rapidly conscripted for a much more ambitious project in the much-superior novel Greenmantle (1916),5 in which he became part of a team carrying out an officially-sanctioned dangerous mission in enemy territory.

It was Greenmantle that became the key model for the entire subgenre of secret agent fiction, and Leroux was probably aware of its existence before penning Rouletabille chez Krupp, although Leroux’s novel is very different in style and attitude, shunning the dogged “stiff upper lip” that Buchan displayed and celebrated more than any other British writer in favor of an archetypally French verve and panache. Leroux had, however, already anticipated some of the features of the shift toward clever teamwork in the previous Rouletabille novel, Rouletabille à la guerre [Rouletabille at War], which began serialization in Le Matin in March 1914, although the serialization was interrupted by the outbreak of the war just as it was reaching its climax, and the last half-dozen of its 135 episodes did not appear until October.6

The text of Rouletabille chez Krupp refers back to the earlier collective adventure several times, usually citing its most significant setting. Rouletabille à la guerre was by no means the first action/adventure novel to cash in on the useful formula of a tightly-knit group of heroes working under the supervision of a charismatic leader to accomplish a seemingly-impossible mission, but it was a significant deployment of the narrative move, which provided a robust foundation for Rouletabille chez Krupp.

Leroux had not intended Rouletabille to be a series character when he first invented him, and had to introduce significant modifications to his back-story when he decided to write a sequel to Le Mystère de la chambre jaune in Le Parfum de la dame en noir (1908-09); tr. as The Perfume of the Woman in Black). The first novel had been set in 1892 but the second has a near-contemporary setting and refers back to the events of the earlier novel as having been set three years earlier. Chronological confusions continued as Rouletabille became a significant early example of a hero who never got any older, although the world around him aged considerably. He was still a “young reporter” in Rouletabille chez le tsar [Rouletabille at the Tsar’s] in 1913, and in Rouletabille chez Krupp in 1917, reflecting the fact that he was a rather nostalgic as well as heavily idealized projection of the author’s own self. In fact, Leroux, who was born in 1868 but only became a professional journalist after the turn of the century, had never been a “young reporter,” having spent his youth squandering the fortune he had inherited in riotous living—although that dubious apprenticeship undoubtedly served him well when he did buckle down to serious journalism, in terms of the contacts he had made and the knowledge of life in the fast lane that he had acquired.

Whatever his origins might have been, however—and in fictional terms, they became fearfully complicated in the process of solving the mystery of the yellow room—by 1917, Rouletabille had become one of those larger-than-life characters who acquire a quasi-archetypal status, and he was, in more ways than one, the ideal character to take on the sort of narrative task that the Ministry of War required of propagandistic fiction. It is significant that Rouletabille chez Krupp, perhaps more than any other novel produced in the same spirit, sets out to demonize the enemy in a remarkably flamboyant fashion, in the key chapters entitled “Le Maître de feu” (tr. as “The Master of Fire”) and “Le Plus Grand Chantage du Monde” (tr. as “The Greater Blackmail of the World”), in which the Krupp armaments factory becomes a transfiguration of Dante’s Inferno, and Kaiser Wilhelm II appears in person to guide the readers around it, in the person of a metaphorical Satan.

The symbolism of these chapters, in which Rouletabille, quietly masquerading as a fireman in the background of the tour, is juxtaposed with both the Kaiser and the gigantic superweapon, the Titania, is decidedly crude, but is perhaps all the more striking because of it. If the story falters thereafter—as it does, to some extent—it is only because the nightmarish quality and bizarre melodrama of the tour and its subsidiary scenes are unsurpassable, and although the bulk of the plot’s ingenuity is devoted to the construction and development of their aftermath, its unraveling could hardly help seeming somewhat trivial by comparison. In the same way, the superweapon itself, having made its awesome symbolic appearance in this sequence, is compelled fade away into a curious oblivion, having done its real job—a narrative inevitability regarding which I shall reserve further comment until an afterword, in order not to give too much away in advance about the story.

Seen in retrospect, Rouletabille chez Krupp is not the best of the Rouletabille novels—although the later ones, Le Crime de Rouletabille [Rouletabille’s Crime] (1921) and Rouletabille chez les Bohémiens [Rouletabille Among the Gypsies] (1922), continued the decline, and would have completed it had not Rouletabille become one of those characters who outlived his author and featured in numerous adventures by other hands in various formats. It is, however, a particularly interesting inclusion in the canon, making more use of Leroux’s fascination with and talent for the bizarre than the other series novels.

It was a novel very much of its moment, and was arguably obsolete before it appeared in book form in 1920, but as a reflection of the imaginative concerns of the French people in 1917 and the revised policy of wartime propaganda that took full effect in that year, it has a stark specificity and punctiliousness that are unmatched.

It requires reading with that historical context in mind, but still makes interesting reading from that perspective.

This translation has been made from the London Library’s copy of the Lafitte edition of 1920.

Brian Stableford

ROULETABILLE AT KRUPP’S

Chapter I

Corporal Rouletabille

When Corporal Rouletabille disembarked on the stroke of five p.m. at the Gare de l’Est, he still had the mud of the trenches on his boots, and he strove more vainly than ever, not to rid himself of a glorious clay that scarcely bothered him, but to guess by what magic spell he had been snatched away from his multiple duties as a platoon-leader in a front-line position at Verdun.

He had received an order to go to Paris as quickly as possible and, as soon as he reached the capital, to go to the offices of his paper, L’Époque. The whole business seemed to him not merely very mysterious but so “anti

-military” that he did not understand it at all.

Even so, in haste as he was to discover the reason for his singular journey, the reporter was glad to walk for a while after long hours spent on the train.

It was the first time he had seen Paris since the outbreak of the war. It was mid-September. The day had been fine. In the oblique rays of sunlight the foliage of the Boulevard de Strasbourg and the Boulevard Magenta was gilded and enflamed, extending its double russet stream toward the heart of Paris. The movement of the city below was full of light and tranquility—just like old times! The young reporter obtained an infinite joy from the sight.

Others before him had come back and had experienced an egotistical pain on seeing the city in its serene pre-war splendor, a few kilometers from the tranches. They had wanted to find a face of suffering in rapport with their own anxieties, anguishes and sacrifices. Rouletabille, however, took a singular pride in it. It’s because I’m out there, he said to himself, that it’s like this here. Well, that, at least, gives me pleasure. People are confident!

And he straightened up in his dishevelment, in his muddy garments.

No one even looked at him. Nor did they pay any more attention to the other poilus who were coming down the Boulevard de Strasbourg, coming back from the front, trailing around them a whole paraphernalia of the noisy war, any more than they paid attention to those who were going back up to the Gare de l’Est, their leave having ended, ready to go forth and resume their mortal sentry-duty, behind which the city had resumed its respiration, the powerful and calm rhythm of its life as the queen of the world.

At the corner of the great boulevards, Rouletabille stopped momentarily, remembering the frightful tumult of the riotous scenes that had desolated this entire quarter of Paris in the early days of mobilization, when a nervous population thought it saw spies everywhere, and a few hooligans had set forth on looting expeditions.

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

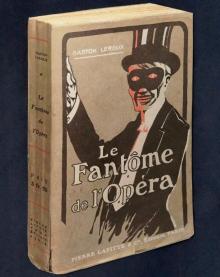

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

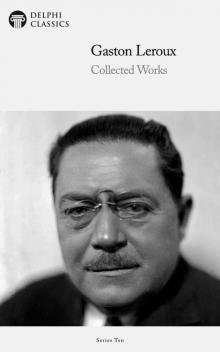

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

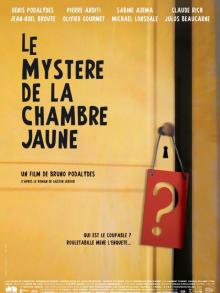

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)