- Home

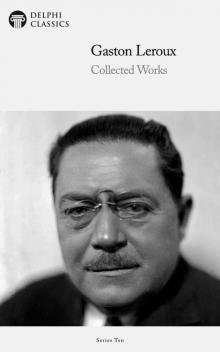

- Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

The Collected Works of

GASTON LEROUX

(1868-1927)

Contents

The Adventures of Rouletabille

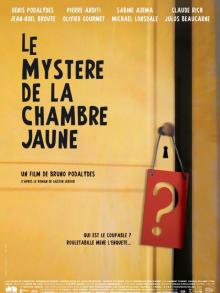

The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907)

The Perfume of the Woman in Black (1908)

Secret of the Night (1913)

The Slave Bangle (1921)

The Sleuth Hound (1922)

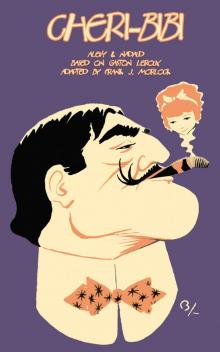

Chéri Bibi Series

The Wolves of the Sea (1913)

Chéri-Bibi and Cecily (1916)

The Dark Road (1921)

The New Idol (1926)

Other Novels

The Man with the Black Feather (1903)

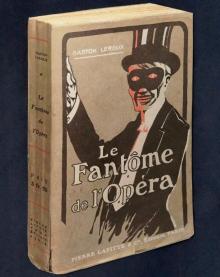

The Phantom of the Opera (1909)

Balaoo (1911)

The Bride of the Sun (1912)

The Amazing Adventures of Carolus Herbert (1917)

The Veiled Prisoner (1917)

The Kiss That Killed (1923)

The Son of Three Fathers (1924)

The Adventures of a Coquette (1924)

The Man of a Hundred Faces (1927)

Lady Helena by Louis Latzarus (1929)

The Short Fiction

Miscellaneous Short Stories

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2020

Version 2

Browse our Main Series

Browse our Ancient Classics

Browse our Poets

Browse our Art eBooks

Browse our Classical Music series

The Collected Works of

GASTON LEROUX

By Delphi Classics, 2020

COPYRIGHT

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

First published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2020.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 91348 706 5

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

From gruesome ghost stories to psychological chillers, the classics are always the greatest stories…

Explore Classic Horror at Delphi Classics…

The Adventures of Rouletabille

Paris — Leroux’s birthplace

Paris in 1868, the year of Leroux’s birth

The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907)

Anonymous 1907 translation

Original French Title: ‘Le mystère de la chambre jaune’

The novel Le Mystère de la Chambre Jaune first appeared as a serial in the periodical L’Illustration from September 1907 to November 1907, before its book publication in 1908. In early twentieth-century terms, Leroux had started his writing career in middle age – his first novel (La Double Vie de Théophraste Longuet — The Double Life), was completed and published in 1904 when he was 36 years old. However, he had been writing short fiction since 1887. Prior to embarking on a career as a novelist, he had been working as a journalist, an experience Leroux put to good use in developing the character of Joseph Rouletabille, the investigator in this story, who is also a reporter. Leroux chose the character’s name with care – Rouletabille (literally roule ta bille or “Roll your marble”) is French slang for “Globetrotter”, one who has been around the world and seen it all; it is also implied in the narrative that the young man received his nickname from his fellow journalists, who likened the shape of his head to a perfectly round billiard ball. The meaning was later expanded to that of a cool-headed, unshockable or nonchalant person. Rouletabille is presented as someone who can think through a mystery in a way that the police cannot do, thus outwitting them in the process. This is a common literary trope in detective stories, but what is unusual about Rouletabille is his youth – he is revealed in the story to be a mere eighteen years old and his real name is Joseph Josephin, a convent educated boy. Leroux’s choice of nickname for the character therefore does have a strong irony to it, implying that the boy has a gift for detection not acquired through life experience. Leroux’s use of a detecting ‘enfant terrible’ is at odds with his own experience — as a young man, Leroux inherited great wealth and then squandered it, only choosing a career out of financial necessity. This is why he turned to journalism and became an international correspondent for Le Matin, most significantly covering the 1905 Russian Revolution.

The novelist Agatha Christie was reportedly a great admirer of the Rouletabille novels and in her teenage years she told a friend that she would like to emulate Leroux by creating her own brilliant detective character. This was some years before the ‘birth’ of Hercule Poirot, her Belgian detective, but commentators have made a direct attribution to the influence of Leroux in the crafting of Poirot.

The Mystery of the Yellow Room is narrated in the first person, by Sainclair, a lawyer that witnessed the events he relates. The mystery of the yellow room and the subsequent trial, happened fifteen years before in October 1892, but Sainclair reveals that the detective who solved the case, Joseph Rouletabille, never did reveal the whole truth of it to either the court or the public: ‘He only allowed so much of it to appear as sufficed to ensure the acquittal of an innocent man.’

Young Rouletabille is sent to investigate a perplexing mystery at the Château du Glandier, situated on the Ile de France, accompanied by his friend Sainclair. Mlle Mathilde Stangerson, the beautiful daughter of the castle’s owner, Professor Joseph Stangerson, has been found badly injured in ‘the Yellow Room’ adjacent to his laboratory on the castle grounds, with the door still locked from the inside. This is a matter of national interest, as Stangerson is what today might be regarded as a ‘celebrity scientist’, the man whose ground breaking research paved the way for the M and Mme Curie to work on their radiography research. The newspapers report the crime as a ‘locked room mystery’. At first the authorities fear for Mathilde’s life; thankfully, she recovers slowly, but she can offer no evidence that would help catch her assailant. Early clues come from Stangerson and the family’s reliable old retainer, Daddy Jaques as he is affectionately known, who heard a struggle and gunshots at around midnight after Mathilde had retired to the Yellow Room. The window is securely locked and the protective bars intact, so they must break down the door to obtain entry to the room which Mathilde had locked from the inside.

The room is in a terrible state, with Mathilde lying close to death from head wounds and evidence of a male attacker having been present. But how did he get in or out with the room so securely locked up, from the inside? Worse still, she was shot with Jacque’s own pistol, which places the old man under suspicion.

Enter Rouletabille, the teenage prodigy who from the age of sixteen has been a gifted investigative journalist. His friend and investigating ‘accomplice’ is Sainclair, a criminal lawyer, who in spite of the age difference between them, liked the young boy immediately upon meeting him and also admired him: ‘His intelligence was so keen and so original! — and he had a quality of thought such as I have never found in any other person.’ For his part, Sainclair was able to advise Rouletabille on points of law and pass on news from his own profession. The two investigators plan to test Rouletabille’s theory that Mathilde had acted from fear in locking herself in the room and had taken the pistol in with her (without telling Jacques, who would have prevented her from doing so) in order to defend herself from an attacker who did indeed come to her.

At the chateau they encounter Robert Darzac, who is also a friend of the Stangersons and is in love with Mathilde. The cast is completed by the arrival of Monsieur Marquet, the examining magistrate, another friend of the two investigators.

Rouletabille sets to work, meticulously studying the layout of the premises. He notes that the Yellow Room is in a pavilion which is separate to the main building of the chateau and he takes careful note of the access points to the pavilion, its doors, windows and aspects. He finds he has a respected rival in the mystery, for Frederic Larsan, France’s most gifted police detective, is assigned to the case – they are to disagree about the possible identity of the attacker. Suspicion falls on members of staff at the chateau and Mathilde’s fiancé, but the case is slow to gather pace. All the while, danger hovers over the chateau and its environs, with the ever present threat of further violence. Before Rouletabille can solve the case, will there be more deaths?

This classic ‘locked room mystery’ is a strong and entertaining opening story for the young detective character of Rouletabille — indeed, it is regarded as one of the pioneers of the genre. Of course, much of the appeal of any mystery such as this is that the reader can play along as an extra detective, but one also needs to keep a firm grip on the numerous male investigators that are involved in the case — Rouletabille and his friend are seemingly working side by side with magistrates, policemen and others close to the Stangerson family. Eventually, however, Rouletabille shines through and his appealing personality and typically gifted detection skills will encourage the reader to follow his other adventures.

Leroux in 1907, the year he wrote ‘Le Mystère de la Chambre Jaune’

The first edition

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. In Which We Begin Not to Understand

CHAPTER II. In Which Joseph Rouletabille Appears for the First Time

CHAPTER III. “A Man Has Passed Like a Shadow Through the Blinds”

CHAPTER IV. “In the Bosom of Wild Nature”

CHAPTER V. In Which Joseph Rouletabille Makes a Remark to Monsieur Robert Darzac Which Produces Its Little Effect

CHAPTER VI. In the Heart of the Oak Grove

CHAPTER VII. In Which Rouletabille Sets Out on an Expedition Under the Bed

CHAPTER VIII. The Examining Magistrate Questions Mademoiselle Stangerson

CHAPTER IX. Reporter and Detective

CHAPTER X. “We Shall Have to Eat Red Meat — Now”

CHAPTER XI. In Which Frederic Larsan Explains How the Murderer Was Able to Get Out of “The Yellow Room”

CHAPTER XII. Frederic Larsan’s Cane

CHAPTER XIII. “The Presbytery Has Lost Nothing of Its Charm, Nor the Garden Its Brightness”

CHAPTER XIV. “I Expect the Assassin This Evening”

CHAPTER XV. The Trap

CHAPTER XVI. Strange Phenomenon of the Dissociation of Matter

CHAPTER XVII. The Inexplicable Gallery

CHAPTER XVIII. Rouletabille Has Drawn a Circle Between the Two Bumps on His Forehead

CHAPTER XIX. Rouletabille Invites Me to Breakfast at the Donjon Inn

CHAPTER XX. An Act of Mademoiselle Stangerson

CHAPTER XXI. On the Watch

CHAPTER XXII. The Incredible Body

CHAPTER XXIII. The Double Scent

CHAPTER XXIV. Rouletabille Knows the Two Halves of the Murderer

CHAPTER XXV. Rouletabille Goes on a Journey

CHAPTER XXVI. In Which Joseph Rouletabille Is Awaited with Impatience

CHAPTER XXVII. In Which Joseph Rouletabille Appears in All His Glory

CHAPTER XXVIII. In Which It Is Proved That One Does Not Always Think of Everything

CHAPTER XXIX. The Mystery of Mademoiselle Stangerson

The first page of the manuscript

Plan of the first floor of the chateau

Plan of the pavilion

CHAPTER I. In Which We Begin Not to Understand

IT IS NOT without a certain emotion that I begin to recount here the extraordinary adventures of Joseph Rouletabille. Down to the present time he had so firmly opposed my doing it that I had come to despair of ever publishing the most curious of police stories of the past fifteen years. I had even imagined that the public would never know the whole truth of the prodigious case known as that of “The Yellow Room”, out of which grew so many mysterious, cruel, and sensational dramas, with which my friend was so closely mixed up, if, propos of a recent nomination of the illustrious Stangerson to the grade of grandcross of the Legion of Honour, an evening journal — in an article, miserable for its ignorance, or audacious for its perfidy — had not resuscitated a terrible adventure of which Joseph Rouletabille had told me he wished to be for ever forgotten.

“The Yellow Room”! Who now remembers this affair which caused so much ink to flow fifteen years ago? Events are so quickly forgotten in Paris. Has not the very name of the Nayves trial and the tragic history of the death of little Menaldo passed out of mind? And yet the public attention was so deeply interested in the details of the trial that the occurrence of a ministerial crisis was completely unnoticed at the time. Now The Yellow Room trial, which, preceded that of the Nayves by some years, made far more noise. The entire world hung for months over this obscure problem — the most obscure, it seems to me, that has ever challenged the perspicacity of our police or taxed the conscience of our judges. The solution of the problem baffled everybody who tried to find it. It was like a dramatic rebus with which old Europe and new America alike became fascinated. That is, in truth — I am permitted to say, because there cannot be any author’s vanity in all this, since I do nothing more than transcribe facts on which an exceptional documentation enables me to throw a new light — that is because, in truth, I do not know that, in the domain of reality or imagination, one can discover or recall to mind anything comparable, in its mystery, with the natural mystery of “The Yellow Room”.

That which nobody could find out, Joseph Rouletabille, aged eighteen, then a reporter engaged on a leading journal, succeeded in discovering. But when, at the Assize Court, he brought in the key to the whole case, he did not tell the whole truth. He only allowed so much of it to appear as sufficed to ensure the acquittal of an innocent man. The reasons which he had for his reticence no longer exist. Better still, the time has come for my friend to speak out fully. You are going to know all; and, without further preamble, I am going to place before your eyes the problem of The Yellow Room as it was placed before the eyes of the entire world on the day following the enactment of the drama at the Chateau du Glandier.

On the 25th of October, 1892, the following note appeared in the latest edition of the “Temps”:

“A frightful crime has been committed at the Glandier, on the border of the forest of Sainte-Genevieve, above Epinay-sur-Orge, at the house of Professor Stangerson. On that night, while the master was working in his laboratory, an attempt was made to assassinate Mademoiselle Stangerson, who was sleeping in a chamber adjoining this laboratory. The doctors do not answer for the life of Mdlle. Stangerson.”

The impression made on Paris by this news may be easily imagined. Already, at that time, the learned world was deeply interested in the labours of Professor Stangerson and his daughter. These labours — the first that were attempted in radiography — served to open the way for Monsieur and Madame Curie to the discovery of radium. It was expected the Professor would shortly read to the Academy of Sciences a sensational paper on his new theory, — the Dissociation of Matter, — a theory destined to overthrow from its base the whole of official science, which based itself on the principle of the Conservation of Energy. On the following day, the newspapers were full of the tragedy. The “Matin,” among others, published the following article, entitled: “A Supernatural Crime”:

“These are the only details,” wrote the anonymous writer in the “Matin”— “we have been able to obtain concerning the crime of the Chateau du Glandier. The state of despair in which Professor Stangerson is plunged, and the im

possibility of getting any information from the lips of the victim, have rendered our investigations and those of justice so difficult that, at present, we cannot form the least idea of what has passed in The Yellow Room in which Mdlle. Stangerson, in her night-dress, was found lying on the floor in the agonies of death. We have, at least, been able to interview Daddy Jacques — as he is called in the country — a old servant in the Stangerson family. Daddy Jacques entered “The Yellow Room” at the same time as the Professor. This chamber adjoins the laboratory. Laboratory and Yellow Room are in a pavilion at the end of the park, about three hundred metres (a thousand feet) from the chateau.

“‘It was half-past twelve at night,’ this honest old man told us, ‘and I was in the laboratory, where Monsieur Stangerson was still working, when the thing happened. I had been cleaning and putting instruments in order all the evening and was waiting for Monsieur Stangerson to go to bed. Mademoiselle Stangerson had worked with her father up to midnight; when the twelve strokes of midnight had sounded by the cuckoo-clock in the laboratory, she rose, kissed Monsieur Stangerson and bade him good-night. To me she said “bon soir, Daddy Jacques” as she passed into The Yellow Room. We heard her lock the door and shoot the bolt, so that I could not help laughing, and said to Monsieur: “There’s Mademoiselle double-locking herself in, — she must be afraid of the ‘Bete du bon Dieu!’” Monsieur did not even hear me, he was so deeply absorbed in what he was doing. Just then we heard the distant miawing of a cat. “Is that going to keep us awake all night?” I said to myself; for I must tell you, Monsieur, that, to the end of October, I live in an attic of the pavilion over The Yellow Room, so that Mademoiselle should not be left alone through the night in the lonely park. It was the fancy of Mademoiselle to spend the fine weather in the pavilion; no doubt, she found it more cheerful than the chateau and, for the four years it had been built, she had never failed to take up her lodging there in the spring. With the return of winter, Mademoiselle returns to the chateau, for there is no fireplace in The Yellow Room.

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)