- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 24

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 24

My alarm, therefore, was great when I saw that the room into which M. le Vicomte de Chagny and I had dropped was an exact copy of the torture-chamber of the rosy hours of Mazenderan. At our feet, I found the Punjab lasso which I had been dreading all the evening. I was convinced that this rope had already done duty for Joseph Buquet, who, like myself, must have caught Erik one evening working the stone in the third cellar. He probably tried it in his turn, fell into the torture-chamber and only left it hanged. I can well imagine Erik dragging the body, in order to get rid of it, to the scene from the Roi de Lahore, and hanging it there as an example, or to increase the superstitious terror that was to help him in guarding the approaches to his lair! Then, upon reflection, Erik went back to fetch the Punjab lasso, which is very curiously made out of catgut, and which might have set an examining-magistrate thinking. This explains the disappearance of the rope.

And now I discovered the lasso, at our feet, in the torture-chamber ! ... I am no coward, but a cold sweat covered my forehead as I moved the little red disk of my lantern over the walls.

M. de Chagny noticed it and asked:

“What is the matter, sir?”

I made him a violent sign to be silent.

22

IN THE TORTURE CHAMBER

THE PERSIAN’S NARRATIVE CONTINUED

We were in the middle of a little six-cornered room, the sides of which were covered with mirrors from top to bottom. In the corners, we could clearly see the “joins” in the glasses, the segments intended to turn on their gear; yes, I recognized them and I recognized the iron tree in the corner, at the bottom of one of those segments ... the iron tree, with its iron branch, for the hanged men.

I seized my companion’s arm: the Vicomte de Chagny was all a-quiver, eager to shout to his betrothed that he was bringing her help. I feared that he would not be able to contain himself.

Suddenly, we heard a noise on our left. It sounded at first like a door opening and shutting in the next room; and then there was a dull moan. I clutched M. de Chagny’s arm more firmly still; and then we distinctly heard these words:

“You must make your choice! The wedding mass or the requiem mass!”

I recognized the voice of the monster.

There was another moan, followed by a long silence.

I was persuaded by now that the monster was unaware of our presence in his house, for otherwise he would certainly have managed not to let us hear him. He would only have had to close the little invisible window through which the torture-lovers look down into the torture-chamber. Besides, I was certain that, if he had known of our presence, the tortures would have begun at once.

The important thing was not to let him know; and I dreaded nothing so much as the impulsiveness of the Vicomte de Chagny, who wanted to rush through the walls to Christine Daaé, whose moans we continued to hear at intervals.

“The requiem mass is not at all gay,” Erik’s voice resumed, “whereas the wedding mass—you can take my word for it—is magnificent! You must take a resolution and know your own mind! I can’t go on living like this, like a mole in a burrow! Don Juan Triumphant is finished; and now I want to live like everybody else. I want to have a wife like everybody else and to take her out on Sundays.1 I have invented a mask that makes me look like anybody. People will not even turn round in the streets. You will be the happiest of women. And we will sing, all by ourselves, till we swoon away with delight. You are crying! You are afraid of me! And yet I am not really wicked. Love me and you shall see! All I wanted was to be loved for myself. If you loved me I should be as gentle as a lamb; and you could do anything with me that you pleased.”

Soon the moans that accompanied this sort of love’s litany increased and increased. I have never heard anything more despairing ; and M. de Chagny and I recognized that this terrible lamentation came from Erik himself. Christine seemed to be standing dumb with horror, without the strength to cry out, while the monster was on his knees before her.

Three times over, Erik fiercely bewailed his fate:

“You don’t love me! You don’t love me! You don’t love me!”

And then, more gently:

“Why do you cry? You know it gives me pain to see you cry!”

A silence.

Each silence gave us fresh hope. We said to ourselves:

“Perhaps he has left Christine behind the wall.”

And we thought only of the possibility of warning Christine Daaé of our presence, unknown to the monster. We were unable to leave the torture-chamber now, unless Christine opened the door to us; and it was only on this condition that we could hope to help her, for we did not even know where the door might be.

Suddenly, the silence in the next room was disturbed by the ringing of an electric bell. There was a sound on the other side of the wall and Erik’s voice of thunder:

“Somebody ringing! Walk in, please!”

A sinister chuckle.

“Who has come bothering now? Wait for me here ... I am going to tell the siren to open the door.”

Steps moved away, a door closed. I had no time to think of the fresh horror that was preparing; I forgot that the monster was only going out perhaps to perpetrate a fresh crime; I understood but one thing: Christine was alone behind the wall!

The Vicomte de Chagny was already calling to her:

“Christine! Christine!”

As we could hear what was said in the next room, there was no reason why my companion should not be heard in his turn. Nevertheless, the viscount had to repeat his cry time after time.

At last, a faint voice reached us.

“I am dreaming!” it said.

“Christine, Christine, it is I, Raoul!”

A silence.

“But answer me, Christine! ... In Heaven’s name, if you are alone, answer me!”

Then Christine’s voice whispered Raoul’s name.

“Yes! Yes! It is I! It is not a dream! ... Christine, trust me! ... We are here to save you ... but be prudent! When you hear the monster, warn us!”

Then Christine gave way to fear. She trembled lest Erik should discover where Raoul was hidden; she told us in a few hurried words that Erik had gone quite mad with love and that he had decided to kill everybody and himself with everybody if she did not consent to become his wife. He had given her till eleven o’clock the next evening for reflection. It was the last respite. She must choose, as he said, between the wedding mass and the requiem.

And Erik had then uttered a phrase which Christine did not quite understand:

“Yes or no! If your answer is no, everybody will be dead and buried!”

But I understood the sentence perfectly, for it corresponded in a terrible manner with my own dreadful thought.

“Can you tell us where Erik is?” I asked.

She replied that he must have left the house.

“Could you make sure?”

“No. I am fastened. I can not stir a limb.”

When we heard this, M. de Chagny and I gave a yell of fury. Our safety, the safety of all three of us, depended on the girl’s liberty of movement.

“But where are you?” asked Christine. “There are only two doors in my room, the Louis-Philippe room of which I told you, Raoul; a door through which Erik comes and goes, and another which he has never opened before me, and which he has forbidden me ever to go through, because he says it is the most dangerous of the doors, the door of the torture-chamber!”

“Christine, that is where we are!”

“You are in the torture-chamber?”

“Yes, but we can not see the door.”

“Oh, if I could only drag myself so far! I would knock at the door and that would tell you where it is.”

“Is it a door with a lock to it?” I asked.

“Yes, with a lock.”

“Mademoiselle,” I said, “it is absolutely necessary that you should open that door to us!”

“But how?” asked the poor girl tearfully.

We heard

her straining, trying to free herself from the bonds that held her.

“I know where the key is,” she said, in a voice that seemed exhausted by the effort she had made. “But I am fastened so tight ... Oh, the wretch!”

And she gave a sob.

“Where is the key?” I asked, signing to M. de Chagny not to speak and to leave the business to me, for we had not a moment to lose.

“In the next room, near the organ, with another little bronze key, which he also forbade me to touch. They are both in a little leather bag which he calls the bag of life and death ... Raoul! Raoul! Fly! Everything is mysterious and terrible here, and Erik will soon have gone quite mad, and you are in the torture-chamber! ... Go back by the way you came. There must be a reason why the room is called by that name!”

“Christine,” said the young man, “we will go from here together or die together!”

“We must keep cool,” I whispered. “Why has he fastened you, mademoiselle? You can’t escape from his house; and he knows it!”

“I tried to commit suicide! The monster went out last night, after carrying me here fainting and half chloroformed. He was going to his banker, so he said! ... When he returned he found me with my face covered with blood ... I had tried to kill myself by striking my forehead against the walls.”

“Christine!” groaned Raoul; and he began to sob.

“Then he bound me ... I am not allowed to die until eleven o’clock tomorrow evening.”

“Mademoiselle,” I declared, “the monster bound you ... and he shall unbind you. You have only to play the necessary part! Remember that he loves you!”

“Alas!” we heard. “Am I likely to forget it!”

“Remember it and smile to him ... entreat him ... tell him that your bonds hurt you.”

But Christine Daaé said:

“Hush! ... I hear something in the wall on the lake! ... It is he! ... Go away! Go away! Go away!”

“We could not go away even if we wanted to,” I said, as impressively as I could. “We can not leave this! And we are in the torture-chamber!”

“Hush!” whispered Christine again.

Heavy steps sounded slowly behind the wall, then stopped and made the floor creak once more. Next came a tremendous sigh, followed by a cry of horror from Christine, and we heard Erik’s voice:

“I beg your pardon for letting you see a face like this! What a state I am in, am I not? It’s the other one’s fault! Why did he ring? Do I ask people who pass to tell me the time? He will never ask anybody the time again! It is the siren’s fault.”

Another sigh, deeper, more tremendous still, came from the abysmal depths of a soul.

“Why did you cry out, Christine?”

“Because I am in pain, Erik.”

“I thought I had frightened you.”

“Erik, unloose my bonds ... Am I not your prisoner?”

“You will try to kill yourself again.”

“You have given me till eleven o’clock tomorrow evening, Erik.”

The footsteps dragged along the floor again.

“After all, as we are to die together ... and I am just as eager as you ... yes, I have had enough of this life, you know ... Wait, don’t move, I will release you ... You have only one word to say: ‘No!’ And it will at once be over with everybody! ... You are right, you are right; why wait till eleven o’clock tomorrow evening? True, it would have been grander, finer ... But that is childish nonsense ... We should only think of ourselves in this life, of our own death ... the rest doesn’t matter ... You’re looking at me because I am all wet? ... Oh, my dear, it’s raining cats and dogs outside! ... Apart from that, Christine, I think I am subject to hallucinations ... You know, the man who rang at the siren’s door just now—go and look if he’s ringing at the bottom of the lake-well, he was rather like ... There, turn round ... are you glad? You’re free now ... Oh, my poor Christine, look at your wrists: tell me, have I hurt them? ... That alone deserves death ... Talking of death, I must sing his requiem!”

Hearing these terrible remarks, I received an awful presentiment ... I too had once rung at the monster’s door ... and without knowing it, must have set some warning current in motion ... And I remembered the two arms that had emerged from the inky waters ... What poor wretch had strayed to that shore this time? Who was “the other one,” the one whose requiem we now heard sung?

Erik sang like the god of thunder, sang a Dies Iræ that enveloped us as in a storm. The elements seemed to rage around us. Suddenly, the organ and the voice ceased so suddenly that M. de Chagny sprang back, on the other side of the wall, with emotion. And the voice, changed and transformed, distinctly grated out these metallic syllables:

“What have you done with my bag?”

23

THE TORTURES BEGIN

THE PERSIAN’S NARRATIVE CONTINUED

The voice repeated angrily: “What have you done with my bag? So it was to take my bag that you asked me to release you!”

We heard hurried steps, Christine running back to the Louis-Philippe room, as though to seek shelter on the other side of our wall.

“What are you running away for?” asked the furious voice, which had followed her. “Give me back my bag, will you? Don’t you know that it is the bag of life and death?”

“Listen to me, Erik,” sighed the girl. “As it is settled that we are to live together ... what difference can it make to you?”

“You know there are only two keys in it,” said the monster. “What do you want to do?”

“I want to look at this room which I have never seen and which you have always kept from me ... It’s woman’s curiosity!” she said, in a tone which she tried to render playful.

But the trick was too childish for Erik to be taken in by it.

“I don’t like curious women,” he retorted, “and you had better remember the story of Blue-Beard1 and be careful ... Come, give me back my bag! ... Give me back my bag! ... Leave the key alone, will you, you inquisitive little thing?”

And he chuckled, while Christine gave a cry of pain. Erik had evidently recovered the bag from her.

At that moment, the viscount could not help uttering an exclamation of impotent rage.

“Why, what’s that?” said the monster. “Did you hear, Christine?”

“No, no,” replied the poor girl. “I heard nothing.”

“I thought I heard a cry.”

“A cry! Are you going mad, Erik? Whom do you expect to give a cry, in this house? ... I cried out, because you hurt me! I heard nothing.”

“I don’t like the way you said that! ... You’re trembling ... You’re quite excited ... You’re lying! ... That was a cry, there was a cry! ... There is some one in the torture-chamber! ... Ah, I understand now!”

“There is no one there, Erik!”

“I understand!”

“No one!”

“The man you want to marry, perhaps!”

“I don’t want to marry anybody, you know I don’t.”

Another nasty chuckle.

“Well, it won’t take long to find out. Christine, my love, we need not open the door to see what is happening in the torture-chamber. Would you like to see? Would you like to see? Look here! If there is some one, if there is really some one there, you will see the invisible window light up at the top, near the ceiling. We need only draw the black curtain and put out the light in here. There, that’s it ... Let’s put out the light! You’re not afraid of the dark, when you’re with your little husband!”

Then we heard Christine’s voice of anguish:

“No! ... I’m frightened! ... I tell you, I’m afraid of the dark! ... I don’t care about that room now ... You’re always frightening me, like a child, with your torture-chamber! ... And so I became inquisitive ... But I don’t care about it now ... not a bit ... not a bit!”

And that which I feared above all things began, automatically. We were suddenly flooded with light! Yes, on our side of the wall, everything seemed aglow. The V

icomte de Chagny was so much taken aback that he staggered. And the angry voice roared:

“I told you there was some one! Do you see the window now? The lighted window, right up there? The man behind the wall can’t see it! But you shall go up the folding steps: that is what they are there for! ... You have often asked me to tell you; and now you know! ... They are there to give a peep into the torture-chamber ... you inquisitive little thing!”

“What tortures? ... Who is being tortured? ... Erik, Erik, say you are only trying to frighten me! ... Say it, if you love me, Erik! ... There are no tortures, are there?”

“Go and look at the little window, dear!”

I do not know if the viscount heard the girl’s swooning voice, for he was too much occupied by the astounding spectacle that now appeared before his distracted gaze. As for me, I had seen that sight too often, through the little window, at the time of the rosy hours of Mazenderan; and I cared only for what was being said next door, seeking for a hint how to act, what resolution to take.

“Go and peep through the little window! Tell me what he looks like!”

We heard the steps being dragged against the wall.

“Up with you! ... No! ... No, I will go up myself, dear!”

“Oh, very well, I will go up. Let me go!”

“Oh, my darling, my darling! ... How sweet of you! ... How nice of you to save me the exertion at my age! ... Tell me what he looks like!”

At that moment, we distinctly heard these words above our heads:

“There is no one there, dear!”

“No one? ... Are you sure there is no one?”

“Why, of course not ... no one!”

“Well, that’s all right! ... What’s the matter, Christine? You’re not going to faint, are you ... as there is no one there? ... Here ... come down ... there! ... Pull yourself together ... as there is no one there! ... But how do you like the landscape?”

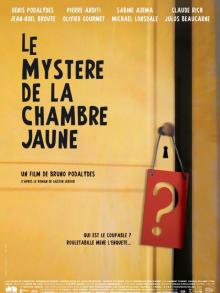

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

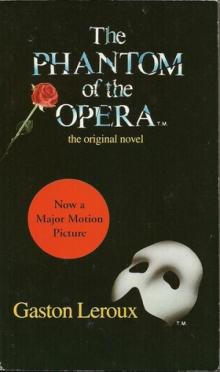

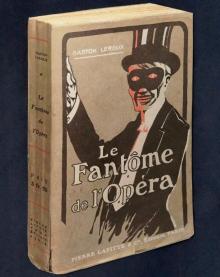

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

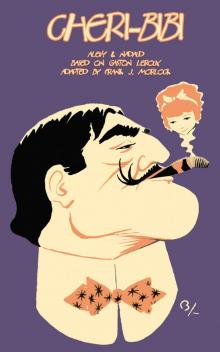

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

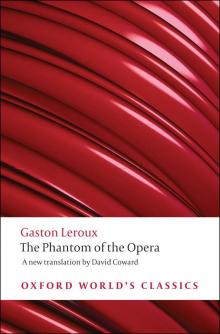

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)