- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 27

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 27

Were we to die here, drowned in the torture-chamber? I had never seen that. Erik, at the time of the rosy hours of Mazenderan, had never shown me that, through the little invisible window.

“Erik! Erik!” I cried. “I saved your life! Remember! ... You were sentenced to death! But for me, you would be dead now! ... Erik!”

We whirled around in the water like so much wreckage. But, suddenly, my straying hands seized the trunk of the iron tree! I called M. de Chagny, and we both hung to the branch of the iron tree.

And the water rose still higher.

“Oh! Oh! Can you remember? How much space is there between the branch of the tree and the dome-shaped ceiling? Do try to remember! ... After all, the water may stop, it must find its level! ... There, I think it is stopping! ... No, no, oh, horrible! ... Swim! Swim for your life!”

Our arms became entangled in the effort of swimming; we choked; we fought in the dark water; already we could hardly breathe the dark air above the dark water, the air which escaped, which we could hear escaping through some vent-hole or other.

“Oh, let us turn and turn and turn until we find the air hole and then glue our mouths to it!”

But I lost my strength; I tried to lay hold of the walls! Oh, how those glass walls slipped from under my groping fingers! ... We whirled round again! ... We began to sink! ... One last effort! ... A last cry:

“Erik! ... Christine! ...”

“Guggle, guggle, guggle!” in our ears. “Guggle! Guggle!” At the bottom of the dark water, our ears went, “Guggle! Guggle!”

And, before losing consciousness entirely, I seemed to hear, between two guggles:

“Barrels! Barrels! Any barrels to sell?”

26

THE END OF THE GHOST’S LOVE STORY

The previous chapter marks the conclusion of the written narrative which the Persian left behind him. Notwithstanding the horrors of a situation which seemed definitely to abandon them to their deaths, M. de Chagny and his companion were saved by the sublime devotion of Christine Daaé. And I had the rest of the story from the lips of the daroga himself.

When I went to see him, he was still living in his little flat in the Rue de Rivoli, opposite the Tuileries. He was very ill, and it required all my ardour as an historian pledged to the truth to persuade him to live the incredible tragedy over again for my benefit. His faithful old servant Darius showed me in to him. The daroga received me at a window overlooking the garden of the Tuileries. He still had his magnificent eyes, but his poor face looked very worn. He had shaved the whole of his head, which was usually covered with an astrakhan cap; he was dressed in a long, plain coat and amused himself by unconsciously twisting his thumbs inside the sleeves; but his mind was quite clear, and he told me his story with perfect lucidity.

It seems that, when he opened his eyes, the daroga found himself lying on a bed. M. de Chagny was on a sofa, beside the wardrobe. An angel and a devil were watching over them.

After the deceptions and illusions of the torture-chamber, the precision of the details of that quiet little middle-class room seemed to have been invented for the express purpose of puzzling the mind of the mortal rash enough to stray into that abode of living nightmare. The wooden bedstead, the waxed mahogany chairs, the chest of drawers, those brasses, the little square antimacassars carefully placed on the backs of the chairs, the clock on the mantelpiece and the harmless-looking ebony caskets at either end, lastly, the whatnot filled with shells, with red pincushions, with mother-of-pearl boats and an enormous ostrich-egg, the whole discreetly lighted by a shaded lamp standing on a small round table: this collection of ugly, peaceable, reasonable furniture, at the bottom of the Opera cellars, bewildered the imagination more than all the late fantastic happenings.

And the figure of the masked man seemed all the more formidable in this old-fashioned, neat and trim little frame. It bent down over the Persian and said, in his ear:

“Are you better, daroga? ... You are looking at my furniture ? ... It is all that I have left of my poor unhappy mother.”

Christine Daaé did not say a word: she moved about noiselessly, like a sister of charity, who had taken a vow of silence. She brought a cup of cordial, or of hot tea, he did not remember which. The man in the mask took it from her hands and gave it to the Persian. M. de Chagny was still sleeping.

Erik poured a drop of rum into the daroga’s cup and, pointing to the viscount, said:

“He came to himself long before we knew if you were still alive, daroga. He is quite well. He is asleep. We must not wake him.”

Erik left the room for a moment, and the Persian raised himself on his elbow, looking around him and saw Christine Daaé sitting by the fireside. He spoke to her, called her, but he was still very weak and fell back on his pillow. Christine came to him, laid her hand on his forehead and went away again. And the Persian remembered that, as she went, she did not give a glance at M. de Chagny, who, it is true, was sleeping peacefully; and she sat down again in her chair by the chimney-corner, silent as a sister of charity who had taken a vow of silence.

Erik returned with some little bottles which he placed on the mantelpiece. And, again in a whisper, so as not to wake M. de Chagny, he said to the Persian, after sitting down and feeling his pulse:

“You are now saved, both of you. And soon I shall take you up to the surface of the earth, to please my wife.”

Thereupon he rose, without any further explanation, and disappeared once more.

The Persian now looked at Christine’s quiet profile under the lamp. She was reading a tiny book, with gilt edges, like a religious book. There are editions of The Imitation1 that look like that. The Persian still had in his ears the natural tone in which the other had said, “to please my wife.” Very gently, he called her again; but Christine was wrapped up in her book and did not hear him.

Erik returned, mixed the daroga a draft and advised him not to speak to “his wife” again nor to any one, because it might be very dangerous to everybody’s health.

Eventually, the Persian fell asleep, like M. de Chagny, and did not wake until he was in his own room, nursed by his faithful Darius, who told him that, on the night before, he was found propped against the door of his flat, where he had been brought by a stranger, who rang the bell before going away.

As soon as the daroga recovered his strength and his wits, he sent to Count Philippe’s house to inquire after the viscount’s health. The answer was that the young man had not been seen and that Count Philippe was dead. His body was found on the bank of the Opera lake, on the Rue-Scribe side. The Persian remembered the requiem mass which he had heard from behind the wall of the torture-chamber, and had no doubt concerning the crime and the criminal. Knowing Erik as he did, he easily reconstructed the tragedy. Thinking that his brother had run away with Christine Daaé, Philippe had dashed in pursuit of him along the Brussels Road, where he knew that everything was prepared for the elopement. Failing to find the pair, he hurried back to the Opera, remembered Raoul’s strange confidence about his fantastic rival and learned that the viscount had made every effort to enter the cellars of the theatre and that he had disappeared, leaving his hat in the prima donna’s dressing-room beside an empty pistol-case. And the count, who no longer entertained any doubt of his brother’s madness, in his turn darted into that infernal underground maze. This was enough, in the Persian’s eyes, to explain the discovery of the Comte de Chagny’s corpse on the shore of the lake, where the siren, Erik’s siren, kept watch.

The Persian did not hesitate. He determined to inform the police. Now the case was in the hands of an examining-magistrate called Faure, an incredulous, commonplace, superficial sort of person, (I wrote as I think), with a mind utterly unprepared to receive a confidence of this kind. M. Faure took down the daroga’s depositions and proceeded to treat him as a madman.

Despairing of ever obtaining a hearing, the Persian sat down to write. As the police did not want his evidence, perhaps the press would be glad of it; a

nd he had just written the last line of the narrative I have quoted in the preceding chapters, when Darius announced the visit of a stranger who refused his name, who would not show his face and declared simply that he did not intend to leave the place until he had spoken to the daroga.

The Persian at once felt who his singular visitor was and ordered him to be shown in. The daroga was right. It was the ghost, it was Erik!

He looked extremely weak and leaned against the wall, as though he were afraid of falling. Taking off his hat, he revealed a forehead white as wax. The rest of the horrible face was hidden by the mask.

The Persian rose to his feet as Erik entered.

“Murderer of Count Philippe, what have you done with his brother and Christine Daaé?”

Erik staggered under this direct attack, kept silent for a moment, dragged himself to a chair and heaved a deep sigh. Then, speaking in short phrases and gasping for breath between the words:

“Daroga, don’t talk to me ... about Count Philippe ... He was dead ... by the time ... I left my house ... he was dead ... when ... the siren sang ... It was an ... accident ... a sad ... a very sad ... accident. He fell very awkwardly ... but simply and naturally ... into the lake! ...”

“You lie!” shouted the Persian.

Erik bowed his head and said:

“I have not come here ... to talk about Count Philippe ... but to tell you that ... I am going ... to die ...”

“Where are Raoul de Chagny and Christine Daaé?”

“I am going to die ...”

“Raoul de Chagny and Christine Daaé?”

“Of love ... daroga ... I am dying ... of love ... That is how it is ... I loved her so! ... And I love her still ... daroga ... and I am dying of love for her, I ... I tell you! ... If you knew how beautiful she was ... when she let me kiss her ... alive ... It was the first ... time, daroga, the first ... time I ever kissed a woman ... Yes, alive ... I kissed her alive ... and she looked as beautiful as if she had been dead! ...”

The Persian shook Erik by the arm:

“Will you tell me if she is alive or dead?”

“Why do you shake me like that?” asked Erik, making an effort to speak more connectedly. “I tell you that I am going to die ... Yes, I kissed her alive ...”

“And now she is dead?”

“I tell you I kissed her just like that, on her forehead ... and she did not draw back her forehead from my lips! ... Oh, she is a good girl! ... As to her being dead, I don’t think so; but it has nothing to do with me ... No, no, she is not dead! And no one shall touch a hair of her head! She is a good, honest girl, and she saved your life, daroga, at a moment when I would not have given twopence for your Persian skin. As a matter of fact, nobody bothered about you. Why were you there with that little chap? You would have died as well as he! My word, how she entreated me for her little chap! But I told her that, as she had turned the scorpion, she had, through that very fact, and of her own free will, become engaged to me and that she did not need to have two men engaged to her, which was true enough.

“As for you, you did not exist, you had ceased to exist, I tell you, and you were going to die with the other! ... Only, mark me, daroga, when you were yelling like the devil, because of the water, Christine came to me with her beautiful blue eyes wide open, and swore to me, as she hoped to be saved, that she consented to be my living wife! ... Until then, in the depths of her eyes, daroga, I had always seen my dead wife; it was the first time I saw my living wife there. She was sincere, as she hoped to be saved. She would not kill herself. It was a bargain ... Half a minute later, all the water was back in the lake; and I had a hard job with you, daroga, for, upon my honour, I thought you were done for! ... However! ... There you were! ... It was understood that I was to take you both up to the surface of the earth. When, at last, I cleared the Louis-Philippe room of you, I came back alone ...”

“What have you done with the Vicomte de Chagny?” asked the Persian, interrupting him.

“Ah, you see, daroga, I couldn’t carry him up like that, at once ... He was a hostage ... But I could not keep him in the house on the lake either, because of Christine; so I locked him up comfortably, I chained him up nicely—a whiff of the Mazenderan scent had left him as limp as a rag—in the Communists’ dungeon, which is in the most deserted and remote part of the Opera, below the fifth cellar, where no one ever comes, and where no one ever hears you. Then I came back to Christine. She was waiting for me ...”

Erik here rose solemnly. Then he continued, but, as he spoke, he was overcome by all his former emotion and began to tremble like a leaf:

“Yes, she was waiting for me ... waiting for me erect and alive, a real, living bride ... as she hoped to be saved ... And, when I ... came forward, more timid than ... a little child, she did not run away ... no, no ... she stayed ... she waited for me ... I even believe ... daroga ... that she put out her forehead ... a little ... oh, not much ... just a little ... like a living bride ... And ... and ... I ... kissed her! ... I! ... I! ... I! ... And she did not die! ... Oh, how good it is, daroga, to kiss somebody on the forehead! ... You can’t tell! ... But I! I! ... My mother, daroga, my poor, unhappy mother would never ... let me kiss her ... She used to run away ... and throw me my mask! ... Nor any other woman ... ever, ever! ... Ah, you can understand, my happiness was so great, I cried. And I fell at her feet, crying ... and I kissed her feet ... her little feet ... crying. You’re crying, too, daroga ... and she cried also ... the angel cried! ...”

Erik sobbed aloud and the Persian himself could not retain his tears in the presence of that masked man, who, with his shoulders shaking and his hands clutched at his chest, was moaning with pain and love by turns.

“Yes, daroga ... I felt her tears flow on my forehead ... on mine, mine! ... They were soft ... they were sweet! ... They trickled under my mask ... they mingled with my tears in my eyes ... they flowed between my lips ... Listen, daroga, listen to what I did ... I tore off my mask so as not to lose one of her tears ... and she did not run away! ... And she did not die! ... She remained alive, weeping over me, with me. We cried together! I have tasted all the happiness the world can offer!”

And Erik fell into a chair, choking for breath:

“Ah, I am not going to die yet ... presently I shall ... but let me cry! ... Listen, daroga ... listen to this ... While I was at her feet ... I heard her say, ‘Poor, unhappy Erik!’ ... And she took my hand! ... I had become no more, you know, than a poor dog ready to die for her ... I mean it, daroga! ... I held in my hand a ring, a plain gold ring which I had given her ... which she had lost ... and which I had found again ... a wedding-ring, you know ... I slipped it into her little hand and said, ‘There! ... Take it! ... Take it for you ... and him! ... It shall be my wedding-present ... a present from your poor, unhappy Erik ... I know you love the boy ... don’t cry any more!’ ... She asked me, in a very soft voice, what I meant ... Then I made her understand that, where she was concerned, I was only a poor dog, ready to die for her ... but that she could marry the young man when she pleased, because she had cried with me and mingled her tears with mine! ...”

Erik’s emotion was so great that he had to tell the Persian not to look at him, for he was choking and must take off his mask. The daroga went to the window and opened it. His heart was full of pity, but he took care to keep his eyes fixed on the trees in the Tuileries gardens, lest he should see the monster’s face.

“I went and released the young man,” Erik continued, “and told him to come with me to Christine ... They kissed before me in the Louis-Philippe room ... Christine had my ring ... I made Christine swear to come back, one night, when I was dead, crossing the lake from the Rue-Scribe side, and bury me in the greatest secrecy with the gold ring, which she was to wear until that moment ... I told her where she would find my body and what to do with it ... Then Christine kissed me, for the first time, herself, here, on the forehead—don’t look, daroga!—here, on the forehead ... on my forehead, mine—don’t look, da

roga!—and they went off together ... Christine had stopped crying ... I alone cried ... Daroga, daroga, if Christine keeps her promise, she will come back soon! ...”

The Persian asked him no questions. He was quite reassured as to the fate of Raoul Chagny and Christine Daaé; no one could have doubted the word of the weeping Erik that night.

The monster resumed his mask and collected his strength to leave the daroga. He told him that, when he felt his end to be very near at hand, he would send him, in gratitude for the kindness which the Persian had once shown him, that which he held dearest in the world: all Christine Daaé’s papers, which she had written for Raoul’s benefit and left with Erik, together with a few objects belonging to her, such as a pair of gloves, a shoe-buckle and two pocket-handkerchiefs. In reply to the Persian’s questions, Erik told him that the two young people, as soon as they found themselves free, had resolved to go and look for a priest in some lonely spot where they could hide their happiness and that, with this object in view, they had started from “the north railway station of the world.” Lastly, Erik relied on the Persian, as soon as he received the promised relics and papers, to inform the young couple of his death and to advertise it in the Epoque.

That was all. The Persian saw Erik to the door of his flat, and Darius helped him down to the street. A cab was waiting for him. Erik stepped in; and the Persian, who had gone back to the window, heard him say to the driver:

“Go to the Opera.”

And the cab drove off into the night.

The Persian had seen the poor, unfortunate Erik for the last time. Three weeks later, the Epoque published this advertisement :

“Erik is dead.”

EPILOGUE

I have now told the singular, but veracious story of the Opera ghost. As I declared on the first page of this work, it is no longer possible to deny that Erik really lived. There are today so many proofs of his existence within the reach of everybody that we can follow Erik’s actions logically through the whole tragedy of the Chagnys.

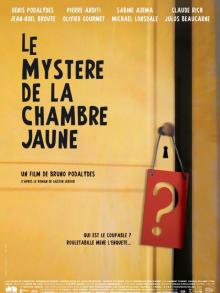

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

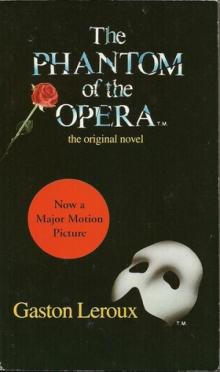

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

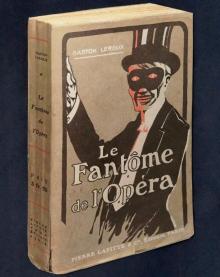

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

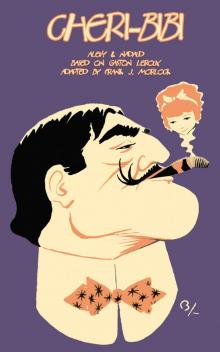

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)