- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Rouletabille at Krupp's Page 9

Rouletabille at Krupp's Read online

Page 9

Another terrible kick on La Candeur’s shoe brought a dull exclamation from the poor fellow.

“I forbid it, you hear!” Rouletabille hissed again, his eyes flashing. “I forbid you to pronounce that figure!”

“All right, all right,” the other sighed. “Understood. All the more so as I’ll end up with corns on my feet if I go on.”

Nothing could be seen of the building but its superstructure. As Nourry had said, it was oddly positioned between workshops, some of which had been half-demolished to “let it pass.” The whole edifice was surrounded by a high and interminable wall of planks, guarded by a cordon of troops.

“Can you believe that they’re taking such precautions? It’s said that special workers are working there, under special surveillance. It’s also said that their new Zeppelin will soon be ready,” La Candeur added. “We’ll soon see what it is—personally, I’m in no hurry. It’s probably one of those defective dodges with which they’re always trying to bluff the world. But what’s the matter with you, old chap? You look as if something...”

Rouletabille’s ears were ringing furiously then, not only because they had been painfully struck by the remark that “it’s said that their new Zeppelin will soon be ready,” but also because he could hear, all along the wall of planks that the prisoners were following behind their guardians, the innumerable echoes of the work that was going on behind it.

A tumult of motors and hammers gave a terrible sensation of the haste with which a population of workers was rushing joyfully and furiously to finish a gigantic task. Every impact broke the reporter’s heart. Will I still have time? he asked himself, his entire body quivering with emotion.

Chapter XIII

Rouletabille Works Hard

Rouletabille succeeded in mastering himself, however, and resolved not to be excited or astonished by anything else until he had triumphed. He listened more attentively to La Candeur’s explanations. A few minutes later, the giant pointed out more buildings to him. “That’s our factory. Look—everything that you can see there is Richter’s kommando.”

Then suddenly, La Candeur said: “Well, old chap, she’s early today.”

“Who?”

“Can’t you see her? There in the little auto that’s stopping outside Richter’s door. The fräulein on the right, in the driver’s seat—that’s his fiancée.”

“Oh yes, Helena. She’s pretty.”

“I’ll say. But I prefer the friend who’s with her, she’s less flaxen—there’s no accounting for taste, you know. The other’s almost chestnut. She’s more like the girls back home, you might say.”

In a changed voice, in spite of having sworn not to be excited by anything else, Rouletabille said: “You…don’t know who her friend is?”

“Honestly, no! It’s not the first time I’ve seen her with Helena Hans. Helena comes to see Richter almost every day. It’s a friend who must live with her in the factory, or they wouldn’t be seen so often together.”

“And when they come together, is that orderly who’s standing with his arms folded behind the car always with them?”

“Yes, always. He must be the chauffeur—but Helena always drives. Look—they’re both getting out and going into Richter’s.”

“Yes, and the orderly’s going with them. You can see that he’s not a chauffeur.”

“Possibly. Does that interest you?”

“Me? Not in the least.”

Rouletabille’s eyes devoured the feminine silhouette that was disappearing though Richter’s doorway between Helena and the orderly. He had recognized Nicole Fulbert.

Yes, it was definitely Nicole, as he had seen her in photographs lent to him by her mother, and as she had been described to him, with her curvaceous stature, her chestnut-colored hair with coppery gleams, her lovely face, always looking down slightly, her bony and slender profile, her large dark blue eyes. Her entire physiognomy gave a strange impression of hostile melancholy...

“We’ve arrived,” said La Candeur.

Indeed, they were going into a large courtyard surrounded by workshops. The workshops were divided into three sections. In the first the heavier components were manufactured: platforms, pedals, levers, axle-trees, flywheels, cylinders, etc. In the second the more delicate components were made: fabric-grips, bobbins, needles, hand-controls, shuttles and even springs. In the third the machines were assembled and finished off. The whole was disposed around a vast courtyard at the back of which were the storage and packing facilities.

Access to this sewing-machine section was obtained via a vast double door, through which all the merchandise went in and came out. At the back of the courtyard there was a small door connecting directly with the buildings of the commando directed by engineer Richter. That was where the latter had his offices, in the middle of a veritable factory devoted almost exclusively to external commerce and foreign exchange.

As soon as they were inside the enclosure, Rouletabille and the other newly-arrived prisoners were subjected to a regulation interrogation by a military foreman, after which the reporter and two of his companions were taken into the engineer’s offices.

They waited there for about ten minutes, and then the reporter was able to take account of the reason for the delay. Through the windows of the room to which they had been taken, he saw Helena appear on the steps of the building, then her companion, then the man who was surely charged with watching Nicole, and finally a man who might have been about forty, rather fat but handsome nevertheless because he was tall. He had to be a solid trencherman and a keen beer-drinker. He had a full blond beard, carefully groomed, and an expansive, highly intelligent face illuminated by two small and piercing gray eyes, which were presently smiling at Helena, whom he accompanied to the automobile. He shook hands with the two young women.

Rouletabille had only darted a glance at the man he assumed to be Richter, all his attention being focused on Nicole. There was no longer any room for doubt; it was definitely Fulbert’s daughter. The unfortunate young woman seemed to have suffered a great deal, and seemed indifferent to everything.

The auto drew away gently, and the man came back into the offices. Two minutes later, he began interrogating the prisoners. It was indeed Richter. Rouletabille’s two companions were rapidly dispatched and headed for the workshops. When the reporter’s turn came, the engineer instructed a secretary to pass him the Blin & Co. file. The employee unlocked a vast filing-cabinet and search through the files arranged there in alphabetical order.

When Richter had the file he opened a door and invited Rouletabille to go through it ahead of him. They went along a corridor and into a large empty room occupied by three large trestle-tables. The tables were strewn with blueprints, machine diagrams and so on. Richter at down on one of the high stools that were distributed around the tables, riffled through the Blin & Co. file momentarily, lingered over the reading of some kind of report, and then turned back to Rouletabille.

“Michel Talmar, you graduated from the École des Arts et Métiers. You were employed by Blin & Co. for five years. You’re a hard worker of remarkable intelligence. In the different workshops through which you passed, you found the opportunity and means to introduce improvements, not only with respect to the work but from the mechanical viewpoint. When the war broke out, you were working at Blin’s, in the greatest secrecy, in drawing up plans for a new sewing-machine, for which you got the idea during a trip you undertook to America in 1907. Blin’s had high hopes for that machine, which would have deployed fifty needles...”

“Seventy-five,” Rouletabille put in.

“Possibly. The secret was well-guarded—to the extent, at least, that it could be. Do you have a contract with Blin’s?”

“No, Monsieur, not yet. It was after examining the plans that I was in the process of drawing up when the war broke out that Blin & Co. were going to make me a firm offer.”

“Can you tell me something about your new machine? You understand that I’m interested. After all

, you’re not bound in any fashion to Blin’s, and it’s a Swiss engineer who’s speaking to you.”

“Who works for Germany.”

“And who corresponds with all the world’s the leading sewing-machine manufacturers. While staying here I can set you up magnificently somewhere else. Except that it’s necessary for me to have some idea, not of the secret of your invention, but of the return one might hope for, the result that you propose to achieve. Anyway, I repeat, can you tell me something about it?”

Rouletabille maintained a meditative silence.

In order to stimulate him, the other said: “The mechanisms of machines are quite variable, when one moves from one model to another, but the principle remains the same, and I don’t think, in any case, that you can bring a veritable revolution to that mechanism, already so refined...”

“Yes I can!” replied Rouletabille, dryly.

“You astonish me!” Richter said, swaying on his stool, with his hands clasped on his knee. “Let’s see: the general functions of a sewing-machine can be divided into three movements. The first is the movement by which the needle plunges into the fabric, drawing the thread in order to seal the loop through which the shuttle will pass. The second is the movement that passes the shuttle or a circular hook through the loop formed by the thread on the needle. The third is the movement displacing the fabric after each stitch, which, in consequence, varies with the length of the stitch. The last movement is called the traction. These three movements are indispensable. They exist in all machines, varying according to the taste and ingenuity of the inventors, and when they’re produced appropriately, all machines sew well if the tensions of the thread, the needle and the shuttle are well-regulated. You can still tell me which of these three movements, in addition to the extraordinary establishment of your seventy-five needles, carries your…improvement.”

“I don’t see any inconvenience, Monsieur, in telling you that my machine takes over those three movements, and that the improvement, as you put it, of the three movements is such that it transforms them completely. You have, of course, seen twenty-five-needle machines; mine, which has seventy-five, and can sew fabrics, hats, leather goods etc., has nothing in common, I can sure you, with those twenty-fives. Its work is unprecedented, and the parallelism between garments is perfect.”

“Yes, but is it always good? In twenty-five-needle machines, for instance, when a thread breaks, the operation continues, and repairs have then to be made on a ordinary machine. With seventy-five needles, I imagine that thread-breakages...”

“With my machine,” Rouletabille put in, curtly, seemingly becoming increasingly excited, “broken threads are of no importance. In your machines, you have a component that forms a knot every eight stitches, in such a way that when the thread breaks, the work is only faulty over the length of those eight stitches. My machine makes a knot at every stitch—and every needle works more rapidly than a needle on one of your machines.”

“Damn!” Richter exclaimed, getting down from his stool and lighting a cigarette. “That is indeed a revolution. Do you smoke, Monsieur?”

“A pipe,” said Rouletabille. “If you’ll permit...”

“Please do. And would it be indiscreet to ask you what the Blins have offered you for...”

“Not at all! Fifty thousand francs on adoption of my plans, and twenty per cent of the profits.”

“Would you like a light?”

“Thanks, but I have my lighter.”

“Monsieur Talmar, I’m delighted to have made your acquaintance.”

“Me too, Monsieur.”

“Monsieur Talmar, you’re not familiar with the Krupp factory?”

“No—regrettably.”

“Well, permit me to give you a little tour of the factory you’d like to know about. It happens that I need to go to the generalkommando this morning.”

The two men looked at one another momentarily, in silence. They had reached an understanding.

“You’ll permit me to give a few orders? I understand from your file that you speak German.”

“Yes, Monsieur...”

“I’m going to telephone for a guard to be put at your disposal. It’s the regulation. You can’t go out without a guard. Excuse me...”

Five minutes later, they were both traversing the factory, with the guard behind them. The engineer gave Rouletabille details of everything they passed en route is a very amiable fashion. He spoke about the factory with great enthusiasm.

“As regards the generalkommando,” he told him, “it’s an unparalleled managerial organization specially dedicated, in the first place, to the foundry, comprising officers from the general staff or the artillery, commanded by a general, all expert in matters of the manufacture of shells and canon. They’re the one who carry out all the experiments and field-trials, and also work tirelessly in the improvement of the materiel, on new discoveries that might be useful to national defense. The services rendered to the war industry by that small nucleus of men are simply staggering. Everything is their work: new cannon, new shells, new kinds of steel, new trench-digging equipment, everything! Now, they’re going to annex to the service inventions of every sort that, outside the foundry, might modify the work of the factory for purely industrial and commercial production.”

“What’s that enormous tower?” asked Rouletabille, without seeming to attach any particular importance to the last sentence that Richter had pronounced, with an evident purpose and while looking at him from the corner of his eye.

“That’s our water-tower. Do you know that, before the war, the annual consumption of water for the Essen steelworks alone surpassed that of the city of Dresden by 225,000 cubic meters. The total figure was fourteen and a half million cubic meters a year. The network of water-pipes comprises 222 kilometers of underground distribution and 143 kilometers interior distribution. Since the war began, the length of the piping has more than tripled. That tells you how important the role played by our water-tower is.”

“I’ve never seen one as high.”

“It’s sixty meters from the base to the lantern! Would you like to go up? From there you can see the entire factory, with its new annexes, and a considerable part of the city of Essen. The view is unique, and the weather is superb today!”

Rouletabille darted a glanced at his watch, which had been taken off him at Rastatt and returned to him when he left for Essen.

“I’d certainly like that,” he said, “but let’s go to your meeting first, because I don’t want to put you out. We can undertake he ascension in question on the way back from the generalkommando.”

“As you wish.”

Almost immediately, Rouletabille saw Richter bow profoundly before a superior officer, who was chatting at a window with a young woman, who raised her head precipitately and sent the engineer her most gracious smile. The reporter recognized Helena—and, half-hidden behind her, the silhouette of Nicole.

It’s true that they’re never apart, he thought. They must live together...

“Before the war,” Richter said, “this was the home of the director of our Energy Laboratory, and the commandant who just saluted us is none other than the director himself, the famous engineer Hans. And look, over there, the building with the three characteristic chimneys—that’s the Energy Laboratory itself. At this moment, there’s some very interesting work on radium going on there...”

In the meantime, Richter and Helena had not stopped smiling at one another in the most amiable fashion.

My opinion, Rouletabille thought, thanking Providence for having caused him to fall upon a Swiss engineer in love, is that the excellent Monsieur Richter took us on a little detour via the water tower in order to have an opportunity to see his beauty again! I don’t have any complaint!

Whatever happened at the generalkommando was quite rapid. Rouletabille was left in a small waiting-room with his guard, who had never ceased to follow him. Ten minutes went by; then Richter came to find our hero and took him into an offic

e where he found himself confronted by two highly-placed individuals whom he subsequently discovered to be General von Berg and the chief engineer to inventions for internal and external commerce and industry. He was asked to repeat what he had already said about his machine, rather brutally, or at least in terms that were intended to disturb him and make him understand that he would not be permitted to keep his secret to himself for very long.

He thought it as well to march in the same direction as the gentlemen in question, and started blushing and stammering in a natural manner that would have delighted La Candeur.

He repeated everything they wanted to hear.

Finally, the chief engineer said to him: “Herr Richter, who is a Swiss subject, has asked us to make you the following offer: two hundred thousand francs on the admission of your plans and thirty per cent of the profits. Think about it! Blin are robbing you! We’ve known Herr Richter for fifteen years. He’s an honest man. Go!”

Richter and Rouletabille went out of the generalkommando, still followed by the soldier.

Richter seemed to have completely forgotten the conversation they had just had at the kommando, but he did not forget to go past the Energy Laboratory again, and the house where Hans and his daughter lived. This time, however, they did not have the pleasure of seeing Helena.

When they reached the water-tower, Rouletabille looked at his watch again. “Shall we go up?” he asked.

“At your disposal,” said Richter.

They went up. The tower was octagonal in shape, and Richter explained as they climbed that its summit enclosed a reservoir of 150 tons. The water, which was brought to the foot of the tower by six-kilometer channels, came from the great artificial lake formed by the exhaustion of the coal mines in the Ruhr basin. Steam-pumps raised the water within the tower and, once in the reservoir, it was propelled by its own weight in all directions within the factory.

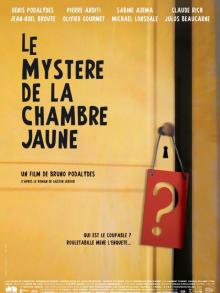

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

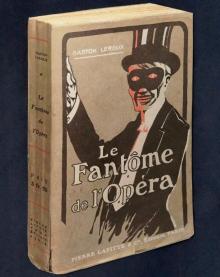

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)