- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room Page 8

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room Read online

Page 8

“He went along the wall there, then jumped over that hedge and ditch. See, just in front of that little path leading to the pond. That’s the quickest way out.”

“How do you know he went toward the pond?”

“Because Frederic Larsan spent all morning there. There must be some important clues there.”

A few minutes later, we reached the pond.

It was a pool of marshy water, surrounded by reeds, on which floated several dead water lilies. Frederic the Great must have seen us approaching, but we probably didn’t interest him enough, since he took little notice of us and continued to be stirring something which we couldn’t see with his cane.

“Look!” said Rouletabille, “here are the footprints of our fugitive! They skirt the pond and finally disappear just before this path, which leads to the main road going to Epinay. From there, the man probably traveled to Paris.”

“What makes you say that?” I asked, “since there are no footprints on that path?”

“What makes me say that, you ask? Why, this other set of footprints, which I expected to find!” he cried, pointing to the clearly defined footmarks left by an expensive pair of boots.

“See!” he said. Then, he called to Larsan: “Monsieur Larsan, were these expensive bootprints already here when the crime was discovered?”

“Yes, young man,” replied the detective, without raising his head. “And we’ve taken careful impressions of them. As you can see, there are two sets of footprints: those coming and those going.”

“And I see that our man had a bicycle!” cried the reporter.

After looking at the tire tracks, which, both coming and going, paralleled the set of expensive bootprints, I thought I was ready to express an opinion.

“The bicycle tracks might explain the disappearance of the perpetrator’s footprints,” I said. “He, in his cheap boots, just rode away on the bicycle. His accomplice, who wears expensive boots, had come to wait for him at the edge of the pond, bringing the bike with him. One might suppose that the perpetrator was working for the man with the expensive boots.”

“No, not at all!” said Rouletabille, with an indulgent smile. “I fully expected to discover these bootprints from the start. They’re my find; I’m not going to let you misinterpret it. They’re the footprints of Mademoiselle Stangerson’s attacker!”

“What about the cheap boots then?”

“They belong to the perpetrator as well.”

“So there were two perpetrators?”

“No, only one man, working alone.”

“Very good! Very good!” said Frederic Larsan from where he stood.

“Look!” continued the young reporter, showing us a section of the ground which had been disturbed by big and heavy heels. “Our man sat here and took off his big, cheap boots, which he had worn only for the purpose of misleading the police. Then, he stood up on his usual boots. After that, taking his cheap boots with him, he quietly made his way to the main road, holding his bicycle in his hand, because he couldn’t ride it on this rough path. What proves it is the lightness of the impression made by the wheels despite the softness of the ground. If a man had been riding the bicycle, the wheels would have sunk more deeply into the soil. So, you see, Sainclair, there was only one man here, the perpetrator, on foot.”

“Bravo! Bravo!” cried Larsan again.

Then, he came suddenly toward us and, planting himself before Monsieur Darzac, said to him:

“If we had a bicycle here, we could demonstrate the correctness of this young man’s reasoning, Monsieur Darzac, would you know if there is one at the Chateau?”

“No!” replied Darzac. “There isn’t. I took mine back to Paris four days ago, the last time I came to Glandier before the crime.”

“That’s a pity!” replied Larsan, rather coldly. Then, turning toward Rouletabille, he added: “If we continue at this rate, we’ll both arrive at the same conclusion soon. Have you any idea as to how the murderer got away from the Yellow Room?”

“Yes,” said my young friend. “I do have an idea.”

“So have I,” said Larsan, “and I’d bet it’s the same as yours. There are no two ways of looking at this case. I’m waiting for the arrival of my superior officer before presenting my report to the Investigating Magistrate.”

“Ah! Is the Chief of the Sûreté coming here?”

“Yes, this afternoon. He’s coming for the reconstruction in the laboratory before the Magistrate. All those who have played any part, big or small, in this tragedy have been summoned to attend. It will be very interesting. It’s a pity you won’t be there.”

“Oh, but I will,” said Rouletabille confidently.

“Really? You’re truly an extraordinary fellow—for your age, I mean!” replied the detective in a somewhat ironic tone. “You’d make a wonderful detective, if only you had a little more method, if you didn’t follow your instincts and those bumps on your forehead. As I’ve noted several times in the past, Monsieur Rouletabille, you reason too much. You don’t allow yourself to be guided by only your observations. What did you think about the blood-stained handkerchief and the bloody handprint on the wall of the Yellow Room? You have seen the handprint and I, only the handkerchief. What conclusions did you draw?”

“Easy!” said Rouletabille, somewhat surprised. “The perpetrator was wounded in the hand by Mademoiselle Stangerson’s revolver!”

“Ah! A purely instinctual observation! Take care, Monsieur Rouletabille, you’re much too logical. Logic will end up playing tricks on you if you follow it blindly. There are times when you must challenge it, almost transcend it… You’re right when you say that Mademoiselle Stangerson fired her revolver, but you’re just as wrong when you say that she wounded the murderer in the hand.”

“I am sure of it,” cried Rouletabille.

Larsan, imperturbable, interrupted him:

“That’s the result of a faulty or incomplete observation! The examination of the handkerchief, the numerous small drops of blood on the floor, drops which I determined were under the footprints of the perpetrator when he walked, prove to me that the perpetrator wasn’t wounded at all, Monsieur Rouletabille. He bled from his nose!”

Larsan spoke very seriously. I couldn’t refrain from uttering an exclamation.

Rouletabille looked gravely at the detective, who did the same. Then, Larsan concluded:

“The man first bled into his hand and handkerchief, then he swiped that hand against the wall. The fact is very important,” he added, “because there is no need for him to be wounded in the hand in order to be guilty.”

Rouletabille seemed to be thinking deeply.

“There is something else, Monsieur Larsan,” he finally said, “that is much more dangerous than following logic blindly. It is the predisposition of some detectives to twist logic to make it serve their own, preconceived notions. I know that you already have your own theory about the murderer’s identity. Don’t bother denying it. But it requires that the perpetrator shouldn’t have been wounded in the hand, otherwise it collapses. So you’ve looked and found another possibility. It’s dangerous, very dangerous, to start from a preconceived idea and then to find the evidence you need to back it up. That method might lead you astray. Watch out, Monsieur Larsan, you’re on a path that’s taking you right into the field of judicial error!”

With his hands in his pockets, an ironic smile and a malicious look in his eyes, Rouletabille was challenging Frederic the Great.

Larsan silently contemplated that young reporter who claimed to be better than he. Then, shrugging, he bowed to us and strode away, hitting the stones in his path with his long cane.

Rouletabille watched him walk away, and then turned toward us, his face joyous and triumphant.

“I shall beat him!” he cried. “I shall beat Larsan at his own game, clever as he is! I shall beat them all, because I, Rouletabille, am smarter than all of them! And as for Larsan, the famous, the illustrious, the wonderful Frederic the Great,

excuse me, but he’s got a turnip for a brain, yes, a turnip!”

And he began a small triumphant gig, but suddenly stopped right in the middle of a step. My eyes followed his gaze; they were fixed on Darzac, who was looking fearfully at the impression left on the path by his feet next to the expensive bootmarks. They were exactly the same!

We thought the Sorbonne Professor was about to faint. His eyes, bulging with terror, avoided ours, while his right hand, with a nervous gesture, twitched at the beard that covered his honest, gentle, and now despairing face. Finally, he regained some of his composure, bowed to us, and said, in a changed voice, that he was obliged to return to the Chateau.

“The Devil!” exclaimed Rouletabille, after Darzac had left.

My friend seemed to be deeply concerned. He tore a sheet of paper from his notebook and, as he had done earlier, cut out the shape of the perpetrator’s expensive bootmarks with his scissors. Then, he fitted this new pattern over Darzac’s footprints. The two were indeed exactly alike.

Rising, Rouletabille exclaimed again: “The Devil!”

I didn’t dare say a word because I realized the grave turmoil that must have been brewing under “those bumps” on my friend’s forehead.

“And yet, I believe Monsieur Darzac to be an honest man,” said Rouletabille with finality.

He then led me on the road to the Auberge du Donjon, which we could see on the highway, by the side of a small clump of trees.

Chapter Ten

“I’d Like Some Blood Pudding”

The Auberge du Donjon didn’t look very impressive, but I like old buildings with their wooden beams blackened with age and the smoke of their fireplaces. I like inns dating back to the days of the stagecoaches, half-crumbling structures that will soon exist only in our memories. They belong to the past, they’re part and parcel of History, they remind us of the folktales of those bygone days when highwaymen roamed our countryside and wild adventures could be had just outside our city walls.

I saw at once that the Auberge du Donjon was at least two centuries old, perhaps even older. Bits of stones and mortar had come loose from the building’s sturdy wood frame, the X- and V-shaped beams of which still firmly supported the aging roof, which had nevertheless slipped forward a little, like a cap on a drunkard’s head. Over the front door, a signboard was swinging creakily as a result of the Autumnal wind. A local artist had decorated it with the picture of a tower with a pointed roof and a lantern, just like that of Glandier. Under it, on the threshold, stood a man with a crabby face, seemingly lost in dark thoughts, at least judging from the wrinkles on his forehead and the knitting of his furry brow.

When we approached, he deigned to take notice of us and asked, in a gruff tone, whether we wanted anything. He was obviously the unfriendly landlord of this otherwise charming inn. As we expressed the desire to have lunch, he told us that he had no food, all the while looking at us suspiciously.

“You don’t have to worry about us,” Rouletabille said. “We’re not with the police.”

“I’m not afraid of the police!” replied the man. “I’m not afraid of anyone!”

With a discreet gesture, I tried to make Rouletabille understand that maybe we should try our luck elsewhere, but my friend was determined to go into that inn, and managed to slip by the man.

“Come on,” he said from the common room. “It’s very nice in here.”

A hearty fire was blazing in the fireplace. We held out our hands to warm them up, as one could already feel winter approaching. The room was quite large, furnished with two heavy tables, some stools, and a counter decorated with rows of bottles of wines and liqueurs. Three windows looked out onto the road. A brightly-colored poster on the wall displayed a pretty young Parisienne naughtily tipping her glass to promote the aperitive virtues of a new brand of vermouth. On the mantelpiece of the fireplace, the innkeeper had displayed an impressive collection of earthenware pots, stone jugs and ceramic dishes.

“That’s a fine fire for roasting a chicken,” said Rouletabille.

“I haven’t got any chicken,” said the innkeeper. “Not even a wretched rabbit.”

“I know,” said my friend in an ironic tone which surprised me. “Then I’d like some blood pudding.”

I confess I didn’t understand what Rouletabille meant by what he had just said, nor why the innkeeper, as soon as he heard it, uttered an oath, quickly stifled it, and began to obey my friend as diligently as Monsieur Darzac had done, when he had heard the words: “The presbytery has lost none of its charm, nor the garden its glow.” Obviously, Rouletabille knew how to make people understand him by using utterly incomprehensible phrases. I said as much to him, but he merely smiled. I would have preferred some kind of explanation, but he put a finger to his lips, which meant not only that he had decided to remain silent, but that he was asking me to do the same.

Meanwhile, the innkeeper had pushed open a small side door and called to somebody to bring half a dozen eggs and a steak. The order was quickly delivered by a pretty young woman with beautiful blonde hair and large, soft eyes, who looked at us with curiosity.

“Get out!” said the innkeeper roughly. “And if the Green Man comes, don’t let me see you!”

She disappeared. Rouletabille took the eggs, which had been brought in a bowl, and the steak, which was on a dish, placed them carefully beside him in the fireplace, unhooked a frying pan and a gridiron, and began to beat up our omelette before proceeding to grill our steak. He then ordered two bottles of cider, and seemed to take as little notice of our host as the latter had done of us earlier. But now, the man was looking at Rouletabille in wonder and at me with undisguised anxiety. He let us do our own cooking and set our table near one of the windows.

Suddenly, I heard him mutter:

“Ah! Here he comes!”

His face changed, now expressing fierce hatred. He went and glued himself to one of the windows, watching the road. I didn’t need to draw Rouletabille’s attention; he had already left our omelette and joined the innkeeper at the window. I went with him.

A man dressed entirely in green corduroy, his head covered with a huntsman’s cap of the same color, smoking a pipe, was walking leisurely on the road. He carried a rifle over his shoulder. His movements displayed an almost aristocratic ease. He looked to be about 45, because his hair and his moustache were peppered with grey. He was remarkably handsome and wore glasses. As he passed near the inn, he seemed to hesitate, as if he was considering whether or not to enter. He gave a glance towards us, took a few puffs of his pipe, and then resumed his walk at the same nonchalant pace.

Rouletabille and I looked at our host. His flashing eyes, his clenched fists, his trembling mouth, advertised his tumultuous feelings all too well.

“He did well to not come in here today!” hissed the innkeeper.

“Who is he?” asked Rouletabille, returning to his omelette.

“The Green Man,” growled the innkeeper. “Don’t you know him? If so, all the better for you! He isn’t a good acquaintance to make. He’s Monsieur Stangerson’s gamekeeper.”

“You don’t appear to like him very much,” said the reporter, pouring his omelette into the frying pan.

“Nobody here likes him, Monsieur. He’s a conceited man who must have been rich himself once, but lost it all, and now he blames everyone for the fact that he’s been forced to become a servant to make a living. Because a gamekeeper is just another servant, right? Upon my word, one would say that he is the master of Glandier, and that all its lands and woods belong to him. He won’t let a poor creature eat a morsel of bread on the grass—his grass!”

“How often does he come here?”

“Too often! But I’m going to make it clear to him that he isn’t welcome here. Until about a month ago, he wasn’t bothering me. It was as if my inn didn’t exist! He had no time for it! He preferred paying court to the pretty landlady at the Auberge des Trois Lys in Saint-Michel. But when the bloom was off that rose, he had to find himse

lf another watering hole. He’s a bad fellow, a rake, a skirt chaser, a scoundrel! There isn’t an honest man around who like him. Why, the caretakers at the Chateau can’t stand the very sight of him!”

“The caretakers are decent people, then, Monsieur?”

“Call me Père Mathieu, Monsieur; everyone else does. And yes, they are, as true as my name’s Mathieu. I believe them to be honest.”

“And yet, they’ve been arrested?”

“What does that prove? But I don’t want to get mixed up in other people’s business...”

“What do you think of the attempt on Mademoiselle Stangerson’s life?”

“She’s a good girl that one, kind, much loved by everyone… What do I think of the attempt on her life?”

“Yes.”

“Nothing… And many things besides… But that’s nobody’s business.”

“Not even mine?” insisted Rouletabille.

The innkeeper looked at him sideways and said gruffly:

“Not even yours.”

The omelette was ready. We sat down at table and were silently eating when the door was pushed open and an old woman, dressed in rags, leaning on a stick, her head doddering, her white hair hanging loosely over her wrinkled forehead, appeared on the threshold.

“Ah! Mère Angenoux! It’s been a long since I’ve seen you,” said our host.

“I’ve been very ill, very nearly dying,” said the old woman. “Would you have any scraps for my Holy Beast, Père Mathieu?”

And she came in, followed by a cat larger than I ever thought could exist. The beast looked at us and gave such a heart-wrenching meow that I shuddered. I had never heard such a lugubrious cry.

As if he’d been drawn by the cat’s meow, a man entered right behind the old woman. It was the Green Man. He saluted by tipping his cap and seated himself at the table next to ours.

“A glass of cider, Père Mathieu,” he said.

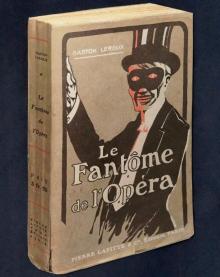

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)