- Home

- Gaston Leroux

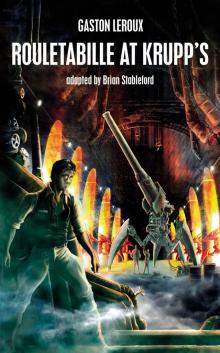

Rouletabille at Krupp's Page 6

Rouletabille at Krupp's Read online

Page 6

“Oh yes? Where is she going?”

“To Rumania! But just between us, she’s going to Turkey.”

“She’s consented to a separation from you?”

“Oh, she’ll come back as soon as possible…and it’s necessary that you know that the end of the war is much closer than is generally believed.”

“Did she tell you that?”

“She did—and, still between the two of us, I can tell you”—Vladimir leaned toward Rouletabille’s ear—“what Enver Pacha told her. Enver Pacha told her himself that the Boche have found an invention so extraordinary that, within a matter of months, nothing—nothing, you hear—will be able to resist them!”

“Bah! And this invention is serious?”

“She was very serious when she told me, my dear chap!”

After that, there was a rather long pause.

“What are you thinking about?” Vladimir asked, eventually.

“I’m thinking about you, Vladimir, and the misapprehension you’re under relative to Rumania’s plans. It will enter the war before long; I can assure you of that—and from the moment that I tell you, you know that it can be taken for granted.”

“Damn!” said Vladimir. “That’s serious!”

“The matter is too serious, where you’re concerned,” Rouletabille replied, “for me to joke about it. Just think that, if you don’t go back to Rumania then, you’ll be considered in France to be a deserter and treated as such. Isn’t that frightful?”

“Which is to say that you’re frightening me. Personally, I don’t see why, having not taken up arms for France or for Russia, I should get myself killed for Rumania!”

“The reasoning seems sound to me,” Rouletabille agreed. “Hold on, though, Vladimir—I’m sure that when you go home, if you examine your identity papers...”

“Of course! That’s what I’m going to do tomorrow. And I’ll find my jurisconsultant again. You can’t imagine how complicated my persona status is!”

“I’m sure,” Rouletabille continued, “that you might well discover that you’re quite simply Turkish—all the more so as you speak Turkish as if it were your mother tongue.”

“Why Turkish? Turkey’s in the war! That would cause many difficulties.”

“There are no difficulties in that direction, when one has money,” Rouletabille replied, “for you know full well that, with money, one doesn’t become a soldier in Turkey.”

“Yes,” said Vladimir, “But I don’t have any money.”

“If that’s all it is, I can lend you some,” said the reporter.

“You like me a little, don’t you, Rouletabille?” said the Slav, hesitantly. “And… and…you’re rich, then?”

“I have, in truth, a great deal of affection for you, Vladimir, and I prove it by continuing to associate with you in spite of your faults, which are enormous. As regards the money question, I can tell you that I’m more at my ease, and that you shall have all the money you need.”

“What for?” asked Vladimir, increasingly astonished.

“To get by in Turkey, of course! Didn’t you tell me that you’re going to become Turkish and go to Turkey with your Princess Botosani, who knows Enver Pacha so well?”

“Oh—yes, I did tell you that...”

The Slav fixed the reporter with eyes shining with intelligence. Suddenly, Rouletabille got to his feet, put his hand on Vladimir’s shoulder and said: “Let’s go smoke a cigarette in the garden.”

There was a large garden behind the house; the light of the moon, which had just risen, showed it to be utterly deserted. The two young men plunged into the hornbeams.

“A Turk and a friend of Enver Pacha!” said Rouletabille, emphatically. “That’s lucky, my friend! Enver is a gallant man who can refuse nothing to women, and since Princess Botosani is so intelligent and so…intriguing, it won’t take long for you to be given some confidential mission—from which, in that country, one invariably comes back padded with gold!”

“I’d like to be padded with gold!” sighed Vladimir. “Tell me what I have to do, Rouletabille, to be padded with gold!”

“Very little, my friend, I assure you. For example: travel the world in luxury trains, allowing oneself to be coddled, pampered and entertained. For in truth, is there any existence more agreeable than that of a gentleman who arrives in a foreign land, charged by his government to negotiate an arms deal, and having the power to increase its magnitude? One does everything to make that man content! One ties oneself in knots as soon as he formulates any desire! And as one is absolutely determined that he will retain an excellent memory of his journey, one does not let him leave without at least giving him what is necessary to put together an entire gold-lined wardrobe if, like you, he has dreamed of one day returning to his beloved fatherland padded with that precious metal.”

“Be quiet, if you’re not talking seriously, Rouletabille, for you’re opening horizons to me—horizons! I can already see myself at Krupp’s, as the representative of young Turkey! With Princess Botosani, Rouletabille, anything is possible.”

“And with you, Vladimir, is everything possible?”

The Slav did not answer immediately. Then, abruptly, he said: “No, not that! No, I can’t! To serve the Turks is to serve the Boche, Rouletabille—and that I’ll never do! Perhaps what I’m going to tell you isn’t very marvelous. Can you imagine that in the early days of September 1914, when the first Uhlan patrols weren’t far from the Eiffel Tower…oh, can you imagine that I wept? Yes, I wept at the thought that the Boche were going to doom Paris! I love your Paris more than you can imagine, you who only know me under a rather ‘devil-may-care’ appearance, and that only certain foreigners can comprehend who have come here once and gone far away, but who always think: I love simply Paris for the pleasure of seeing it, which it gave me! I love Paris because it’s the most chic place in the world…and I’ll never do anything to harm Paris. That’s the way it is!”

Vladimir fell silent. Rouletabille shook his hand in the darkness. “Indeed it is. But what if you were to do something for Paris?”

“Of course—and with what joy, what enthusiasm! Especially…especially, Rouletabille, if I were to be working with you!”

The reporter drew Vladimir deeper into the hornbeams.

Twenty minutes later, when they came back to the threshold of the light poured out by the rooms where people were dancing, Vladimir’s face was particularly grave. The two young men exchanged another firm handshake. Then Vladimir suddenly said: “She’s here!” and went swiftly into the drawing-room.

Rouletabille went back into the ballroom as well, to see the Slav sketching the first moves of a two-step, in company with a heavily made-up and somewhat exotically beautiful young woman.

Rouletabille asked a bystander: “That’s Princess Botosani, isn’t it?”

“Yes, she’s infatuated with Vladimir Féodorovitch. These great ladies, honestly—nothing gets in their way!”

The reporter stayed there for a few moments, studying the princess with great attention, then paid his bill and left the house.

He went back on foot to his small apartment overlooking the Jardins du Luxembourg.

He worked all night, went to bed at five a.m., and was woken up at nine by Vladimir. The two young men remained locked away until noon. At twelve, they re-emerged.

Rouletabille went out in his military uniform, leapt into a cab, and had himself taken to a restaurant in the vicinity of the Avenue de Clichy that was renowned for its tripe, prepared in the Caen style.

Chapter IX

Behind the Lines

Outside the door, a superb general-staff limousine was parked. Rouletabille cast an eye over the magnificent automobile, observing that the chauffeur was neither in his seat nor on the sidewalk, and went into the establishment. He went past the famous steaming boilers, climbed a staircase, went into a large hall, and immediately perceived, sitting at a small table by a window overlooking the Avenue de Clichy, a military man of

imposing stature and corpulence, dressed in immaculate horizon-blues, whose sleeve was ornamented by an armband bearing a large capital A.

That enormous warrior was so busy having the contents of the dishes placed nearby on a warming-plate on to his own plate that he did not even look up when the newcomer came to take possession of the vacant chair at his table. It was not until that unexpected guest sat down directly opposite his plate that he deigned to take notice of the unusual presence.

“Rouletabille!” he exclaimed—and immediately got up, so abruptly that he nearly tipped everything over. He seized the reporter in his arms and hugged him to his mighty bosom.

“Take care, La Candeur!” said Rouletabille. “You’re stifling me!”

“Oh, let me embrace you! It’s been such a long time” My God, you look well! I fear that the trenches…but let’s sit down…let’s not let the tripe get cold! You’ll eat with me? But what miracle brings you here?”

Freed from the benevolent giant’s grip, Rouletabille replied that he was as hungry as a wolf, and that they could chat over dessert.

“Eat, old chap, eat! I’m on my third portion, you know, and my third bottle of cider. Oh, Rouletabille, you don’t know what an appetite the work I’m doing gives me!”

“Yes, yes, I know that one’s very busy in the general staff’s automobiles.”

“Oh, you have no idea! One’s on the go all the time, my dear boy! And it’s necessary to be very sober, you know! And always running errands—for in this job, one has to do everything, even doing the colonel’s shopping in the big stores. You have no idea, I tell you!”

And the giant sighed, causing the rest of his plateful to disappear—and ordering two more.

“I can see that you’re very unhappy, deep down, my poor La Candeur. And in truth, I grieve for you. But isn’t it your own fault, to some extent? Why didn’t you come with us to the trenches? One has leisure time in the trenches! Not to mention that one isn’t poorly nourished, by any means! And one has time to play cards—your passion!”

“Yes, I’m told that there are some good games there.” Visibly embarrassed by the direction in which Rouletabille was taking the conversation, La Candeur went on: “Speaking of cards, do you have any news of that animal Vladimir?”

“None! It’s ages since I’ve seen him; I’ve had no more news of him than of you! And you pretend that you love me!”

La Candeur’s face went crimson. He raised an enormous fist above the table. “Me! I don’t love you?”

Rouletabille stopped the fist, which would have smashed everything. “Calm down, La Candeur, and answer me.”

“I’ll answer you right away,” said La Candeur, who was stammering and seemed to be about to choke. “When war was declared, things happened so fast that we didn’t even have time to see one another. We were separated immediately…me, I was in the transport service…I swear to you, Rouletabille, that I did everything I could to join you! Finally, I resigned myself to it. It was only when I had been convinced that it was impossible for me, by any means, to go and fight by your side, having had a few difficulties with my superiors because of two horses that had been killed under me...”

“What!” Rouletabille exclaimed. “You’ve had two horses killed beneath you, and you don’t have the croix de guerre?”

“My God, they were very small horses, which had no resistance…you understand? I only had to sit on them, and that was that!”

“Yes, yes, they were flattened and died.”

“Something like that. Anyway, they didn’t have any reason to give me the croix de guerre. That was when I had the idea that, since I couldn’t ride a horse without some misfortune overtaking it, it would be preferable all round if I manned an automobile! I had a few connections…I used them…and that’s the whole story. Now, I’ll tell you, just between the two of us, that I’m not a mighty warrior…far from it…and you know that full well, and I couldn’t go with you…so I’ll admit to you that I’m not too upset that things worked out the way they did, since I couldn’t go with you...”

Rouletabille looked La Candeur in the face. The latter’s disturbance only increased. And suddenly, the Époque reporter decided to speak.

“La Candeur, I’ve come to tell you that your troubles are over—you can come with me now!”

The giant took the blow bravely. He did not faint, although, all in all, he loved Rouletabille so much that might have been overcome with joy. He could not speak for some time, though and he began going red and pale by turns, an obvious sign of great emotion.

Finally, he was able to say: “You’re not joking?”

“Do I look as if I’m joking?”

In fact, Rouletabille had never seemed so serous. He was now looking at La Candeur as seriously as possible.

“It’s not necessary,” Rouletabille said, “for that to stop you eating.”

“No thanks—I’ve finished. You’ve…cut off my appetite. I’ll wait a little. I’m so surprised…and glad...”

“You’re sure that you’re glad?”

“I’d put my hand in the fire! Obviously, I’m all of a dither…but that must be gladness. I love you so much, Rouletabille...”

The latter did not smile. He knew perfectly well what was going through the worthy giant’s mind. He did not doubt the immense amity that the giant had for him, but he also knew that his incredible timidity had made La Candeur an individual who was not very combative, in spite of his redoubtable appearance. Certainly, at critical moments, La Candeur was brave, and had often proved it—but outside of those critical moments, he did not believe in his own bravery! So, the battle that was going on in the heart of his vast friend, whose ups and downs Rouletabille could follow very well, made him feel genuinely tender. He knew that friendship would emerge victorious from the struggle; he would appreciate La Candeur’s devotion all the more in consequence.

The end of the meal was calm—all the calmer because La Candeur was no longer eating or drinking. From time to time, in a grave tone, he asked for details of the life led by the troopers in the trenches, the dangers they ran, the intensity of the bombardment, and the science of the cooks.

Rouletabille answered him calmly and untiringly. When the time came to get up from the table, however, he said to his friend: “Are you so very interested, then, in the life one leads in the trenches, La Candeur?”

“What? Of course it interests me—isn’t it understood that from now on. I’ll be leading that life with you?”

“With me? But I’m not going back to the trenches!”

“Where are you going, then?”

“My dear La Candeur, we’re both going to a sewing-machine factory!”

“A sewing-machine factory?”

They had arrived on the sidewalk beside the magnificent general-staff automobile. Planted in front of Rouletabille, La Candeur stood there open-mouthed, utterly bewildered.

“Well, what, La Candeur? Don’t you want to go to a sewing-machine factory?”

“Yes, yes…damn it! But obviously, I’m wondering why?”

Rouletabille leaned closer to the giant’s ear. “It seems that the State has, at present, a great need for sewing-machines.”

“Really?”

“Just as I say.”

“But I’ve never manufactured sewing-machines myself.”

“Well, you’ll learn.”

La Candeur let out an enormous laugh, and clapped Rouletabille on the shoulder so hard that the latter had to hold on to the automobile in order not to end up in the gutter.

“Sewing-machines! Sewing-machines! We’re in sewing-machines now? Oh, how novel, old man! Well, it’ll need a long trip in the Bois to get me over so much excitement. Let’s go take our constitutional, Rouletabille!” And he invited the reporter to take the seat next to him. He drew off at speed immediately, repeating like a joyful litany: Sewing-machines! Sewing-machines!”

At the corner of the Avenue du Bois they nearly crashed into a beautiful car whose chauffeur

was copiously cursed by La Candeur—but all of a sudden, the latter exclaimed; “Rouletabille! Look into that car!”

Rouletabille had already seen and recognized Princess Botosani and, by her side, relaxing on the cushions, the handsome Vladimir...

La Candeur sat up in his seat and shouted at his former companion in adventure: “It’s all right for some, behind the lines!”

Chapter X

Essen

Essen! Essen! Rouletabille finally caught sight of Essen.

For more than an hour, already, the train that was carrying him had been going through a landscape that he knew well, but which he no longer recognized. He recalled his previous astonishment at the prodigious activity of that human inferno. What could be said about it today?

Where there had once been a city, he found a world. The feldwebel, behind him, who was watching him and permitted him to put his nose out of the window, gave him he details.

Before the war, Essen had had less than 30,000 inhabitants. Now it had more than a million, and 120,000 of those citizens worked in the factories night and day. The latter now employed at least 300,000 workers, 60,000 of whom were women, working n shifts night and day.

The feldwebel told him all that with pride, and certainly under orders, undoubtedly to lower the morale of the prisoners he was guarding…but Rouletabille’s morale was solid.

The reporter had not lost any time since the day when, in Paris, he had been given the word to “go!” He had overcome difficulties of every sort.

To begin with, Nourry’s murder had been a veritable disaster for Rouletabille. Nourry would have been able to furnish him with a hundred precious details regarding the life of the prisoners at Essen and the conditions of their work in the factories. Rouletabille would have been able to extract from his still-recent memories all kinds of things useful to his enterprise; he might have found a departure-point therein for one of those flights of the imagination with which the reporter was accustomed to confront material obstacles that would have been insurmountable for anyone else.

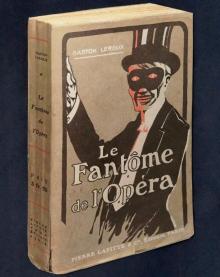

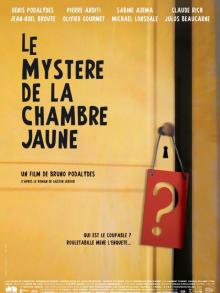

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)