- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Page 51

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

Page 51

Turning to me, he continued:

“M. Sainclair, you ought to know that I never suspect any person or anything without previously having satisfied myself upon the ‘ground of pure reason.’ That is a solid staff which has never yet failed me on the road and on which I invite you all to lean with me. Larsan is here among us, and the power of pure reason is going to show him to you; so be seated again, if you please, and do not take your eyes from me, for I am going to begin on this paper the corporeal demonstration of the possibility of ‘the body too many’!”

First of all, he investigated to make sure that the bolts of the door behind him were closely drawn; then, returning to the table, he took up a compass.

“I have the intention of making my demonstration,” he said, “along the same lines on which the ‘body too many’ has produced itself. It will be, thereby, only the more irrefutable.”

And, with his compass, he took, upon M. Darzac’s drawing, the measure of the radius of the circle which represented the space occupied by the Tower of the Bold, so that he was immediately afterward able to trace the same circle upon an immaculate piece of white paper which he had fastened with copper-headed nails to another drawing board.

When the circle was traced, Rouletabille, putting down his compass, picked up the tiny dish of red paint and asked M. Darzac whether he recognized it as the coloring matter he had used. M. Darzac, who, from all appearances, understood the significance of the young man’s words and actions no better than the rest of us, replied that, to the best of his belief, it was the same paint which he had mixed for his wash drawing.

A good half of the paint had dried up in the bottom of the dish, but, according to the opinion expressed by M. Darzac, the part which remained would, upon paper, give nearly the same tint with which he had “washed” the drawing of the peninsula of Hercules.

“No one has touched it,” said Rouletabille very gravely, “and nothing has been added to it, save a single tear. Besides, you will see that a tear more or less in the paint cup would detract nothing from the value of my demonstration.”

Thus saying, he dipped the brush in the paint and began carefully to “wash” all the space occupied by the circle which he had previously traced. He did this with the care and exactitude which had already astonished me in the Tower of the Bold when I had been nearly stupefied in seeing him absorbed in a drawing when we knew that someone had been assassinated.

When he had finished he looked at his immense silver watch and said:

“You may see, ladies and gentlemen, that the coating of paint which covers my circle is neither more nor less thick than that which covers the circle of M. Darzac. It is almost the same thing — the same tint.”

“Undoubtedly,” rejoined M. Darzac. “But what does all this signify?”

“Wait!” replied the reporter. “It is understood, then, that it is you who have made this plan and this painting?”

“I was certainly in enough of an ill humor when I found the state it was in that time I went with you into Old Bob’s cabinet when we came out of the Square Tower. Old Bob had ruined my drawing by letting his skull roll over it.”

“We are there!” spoke up Rouletabille, quick as a flash. And he lifted from the bureau the “oldest skull of the human race.” He turned it over and showed the crimsoned jaws to M. Darzac. Then he inquired:

“Is it your opinion that the red which we see upon that under jaw is no different from the red which would be taken off by any object coming in contact with your plan?”

“I don’t see how there could be any doubt of it! The skull was upside down on my drawing when we entered the workshop.”

“Let us continue then to remain of the same opinion!” said the reporter.

Then he arose, holding the skull in the crook of his arm, and went into the alcove in the wall, lighted by a large window and crossed by bars, which had been a loophole for cannon in the ancient times, and which M. Darzac had used as a dressing room. There he struck a match and lighted a lamp filled with spirits of wine which stood upon a little table. Upon this lamp he set a little pot which he had previously filled with water. The skull still lay in the crook of his arm.

During this weird cookery, we never took our eyes off him. Never had Rouletabille’s behavior appeared to us so incomprehensible nor so mysterious nor so disturbing. The more he explained matters to us and the more he did, the less we understood. And we were afraid because we felt that someone — someone among us — one of ourselves — had reason for fear. Who was this one? Perhaps the most calm of us all!

But the calmest of all was Rouletabille between his skull and his casserole.

But what? Why did we all suddenly recoil with a single movement? Why were the eyes of M. Darzac wide with a new terror — why did the Lady in Black — Arthur Rance — I, myself — utter the same syllable — a name which expired on our lips: “Larsan!”?

Where had we seen him? Where had we discovered him this time, we who were gazing at Rouletabille? Ah, that profile, in the red shadow of the approaching twilight, that brow in the background of the alcove upon which the sunset rays stream as did the dawn on the morning of the crime! Oh, that stern jaw, bespeaking an iron will, which appeared before us, not, as in the light of day, gentle though a little bitter, but evil and threatening. How like Rouletabille was to Larsan! How in that moment the son resembled his father! It was Larsan’s very self!

Another transformation. At a moan from his mother Rouletabille came out of his funereal frame and appeared before us as a bandit, and as he hurried toward us, he was Rouletabille once more. Mme. Edith, who had never seen Larsan, could not understand. She whispered to me, “What is going on?”

Rouletabille was there before us with his hot water in the casserole, a napkin and his skull. And he washed the skull.

It was soon done. The paint disappeared. He made us bear witness to the fact. Then, placing himself in front of the bureau, he stood in mute contemplation before his own drawing. This lasted for ten minutes, during which he had, by a sign, ordered us to keep silence — ten minutes which seemed as long as the same number of hours. What was he waiting for? What did he expect? Suddenly, he seized the skull in his right hand, and with the gesture familiar to those who play at bowling, he tossed it about so that it rolled hither and yon over the drawing; then he showed us the skull and bade us notice that it bore no trace of red paint. Rouletabille drew out his watch again.

“The paint has dried upon the plan,” he said. “It has taken a quarter of an hour to dry. Upon the 11th of April we saw at five o’clock in the afternoon, M. Darzac entering the Square Tower and coming from out of doors. But M. Darzac, after having entered the Square Tower, and after having fastened behind him the bolts of his door, as he tells us, has not gone out again until we came to fetch him after six o’clock. As to Old Bob, we had seen him enter the Square Tower at six o’clock and there was no paint on this skull then!

“How was this paint which has taken only a quarter of an hour to dry upon this plan, fresh enough still — more than an hour after M. Darzac had left it — to stain Old Bob’s skull when the savant, with a movement of anger, threw it down on the plan as he entered the Round Tower? There is only one explanation of this, and I defy you to find another — and that is that the Robert Darzac who entered the Square Tower at five o’clock and whom no one has seen going out again, was not the same as the one who came to paint in the Round Tower before the arrival of Old Bob at six o’clock and whom we found in the room in the Square Tower without having seen him enter there and with whom we went out. In one word — he was not the same man as the M. Darzac here present before us. The testimony of pure reason shows that there are two personalities appearing in the guise of Robert Darzac!”

And Rouletabille turned his eyes full upon the man whose name he had uttered.

Darzac, like all the rest of us, was under the spell of the luminous demonstration of the young reporter. We were all divided between a new horror and a boundless ad

miration. How clear was every word that Rouletabille had uttered! How clear — and how terrible! Here again we found the mark of his prodigious and logical mathematical intelligence!

M. Darzac cried out:

“It was thus, then, that he was able to enter the Square Tower under a disguise which made him, without doubt, my very image! It was thus that he was able to hide behind the panel in such a way that I did not see him myself when I came here to write my letters after quitting the Tower of the Bold, where I left my drawing. But how could Pere Bernier have opened to him?”

“Doubtless,” replied Rouletabille, who had taken the hand of the Lady in Black in both his own as though he wished to give her courage, “he must have believed that it was yourself.”

“That then explains the fact that when I reached my door I had only to push it open. Pere Bernier believed that I was within.”

“Exactly: that is good reasoning!” declared Rouletabille. “And Pere Bernier, who had opened to Darzac No. 1, had not troubled himself about No. 2, since he did not see him any more than yourself. You certainly reached the Square Tower at the moment that Sainclair and myself called Bernier to the parapet to see whether he could help us in understanding the strange gesticulations of Old Bob, talking at the threshold of the Barma Grande to Mrs. Rance and Prince Galitch.”

“But Mere Bernier!” cried M. Darzac. “She had gone into her lodge. Was she not astonished to see M. Darzac come in a second time when she had not seen him go out?”

“Let us suppose,” replied the young reporter with a sad smile; “let us suppose, M. Darzac, that Mere Bernier at that moment — the moment when you passed into your apartments — that is to say, when the second apparition of Darzac passed in — was occupied in picking up the potatoes and putting them back into the sack which I had emptied upon her floor — and we shall suppose the truth.”

“Well, then, I can congratulate myself on the fact that I am still upon earth!”

“Congratulate yourself, M. Darzac? congratulate yourself!”

“When I remember that as soon as I entered my room, I drew the bolts as I have told you that I did, that I began to work and that this wretch was hidden behind my back. Why, he might have killed me without hindrance!”

Rouletabille stepped close to M. Darzac and fixed his eyes upon him with a look that seemed to read his soul.

“Why did he not kill you then?” he asked.

“You know very well that he was waiting for someone else,” replied M. Darzac, turning his face sorrowfully toward the Lady in Black.

Rouletabille was now so close to M. Darzac that their shadows on the floor looked like that of one strangely formed being. The lad put his two hands on the older man’s shoulders.

“M. Darzac,” he said, his voice again clear and strong, “I have a confession to make to you. When I began to understand how the ‘body too many’ had effected an entrance and when I had discovered that you did nothing to undeceive us in regard to the hour of five o’clock at which we had believed — at which everyone, rather, except myself, believed — that you had entered the Square Tower, I felt that I had the right to suspect that the murderer was not the man who at five o’clock entered the Square Tower under the form of Darzac. I thought, on the contrary, that that Darzac might be the true Darzac and you might be the false one. Ah, my dear M. Darzac, how I have suspected you!”

“That was madness!” cried M. Darzac. “If I did not tell you the exact hour at which I entered the Square Tower it was because the time was somewhat vague in my own mind and I did not attach any importance to it.”

“In such a manner, M. Darzac,” continued Rouletabille, without paying any attention to the interruptions of his interlocutor, the emotion of the Lady in Black and our attitude, more than ever filled with terror. “In such a manner as that you could have stolen away the true Darzac when he came from outside and, by your own carefulness and the too faithful help of the Lady in Black, could have taken his place and have been perfectly able to defy detection of your audacious enterprise. This was my imagination — only my imagination, M. Darzac; don’t let it disturb you. But in such a manner as this, I had thought that, you being Larsan, the man who was put in the sack was Darzac. Ah! the fancies that I have had! and the useless suspicions!”

“Bah!” responded Mathilde’s husband, gloomily. “We are all suspicious here!”

Rouletabille turned his back upon M. Darzac, put his hands in his pocket and said, addressing himself to Mathilde, who seemed ready to swoon before the horror of Rouletabille’s imaginings:

“Courage for a little while longer, Madame!”

And he began speaking again, in his “teacher’s” voice which I knew so well, and with the air of a professor of mathematics propounding or resolving a theorem:

“You see, M. Darzac, there are two manifestations of Robert Darzac. To know which was the true one and which was the one which formed a disguise for Larsan — my duty, M. Darzac — that which the power of pure reason showed me — was to examine, without fear or reproach, both of these manifestations — in all impartiality. Thus, I begin with you — M. Darzac.”

M. Darzac replied:

“It does not matter since you suspect me no longer. But you must tell me immediately who is Larsan. I insist upon it — I demand it!”

“We all demand it — and at once!” we all cried, turning upon both of them. Mathilde rushed up to her child and placed herself in front of him, as if to protect him. We felt the pathos of her attitude but the scene had endured too long and we were beyond the limits of patience.

“If he knows who is Larsan let him speak out and make an end of this!” exclaimed Arthur Rance.

And suddenly, just as the thought crossed my mind that I had heard the same cries of anger and impatience two years before at the Court of Assizes, another pistol shot sounded outside the door of the Square Tower, and we were all so seized with consternation that our anger fell away in a moment and we found ourselves not threatening Rouletabille but entreating him to put an end as soon as possible to this intolerable situation. At this moment, it actually seemed as though we were each imploring him to speak out, as though we calculated that by doing so, we would prove, not only to the others but to ourselves, that we were not Larsan.

As soon as the second shot was heard, the countenance of Rouletabille changed completely. His face seemed transformed and his whole being appeared to vibrate with a savage energy. Laying aside the half bantering manner which he had used toward M. Darzac and which we had all found extremely disagreeable, he gently released himself from the clasp of the Lady in Black, who still clung to him, walked toward the door, folded his arms and said:

“You see, my friends, in an affair like this, it does not do to neglect any point. There were two manifestations of Robert Darzac which entered the Square Tower. There were two manifestations which came out — and one of these was in the sack! That is where one loses oneself. And even now, I do not wish to make any mistakes! Will M. Darzac, here present, permit me to say that I had a hundred excuses for suspecting him?”

Then I thought to myself: “How unlucky that he did not mention his suspicions to me! I would have told him about the map of Australia!”

M. Darzac strode across the room and planted himself in front of the young reporter and said in a tone nearly inaudible from anger:

“What excuses? I ask you, what excuses?”

“You will soon understand, my friend,” said the reporter with the utmost calmness. “The first thing that I said to myself while I was examining the conditions surrounding your manifestation of Larsan, was this: ‘Nonsense! if he were Larsan, would not Professor Stangerson’s daughter have perceived it?’ That is self evident — the common sense of that thought — is it not? But when I tried to look into the mind of the lady who has become Mme. Darzac, I discovered beyond a doubt, Monsieur, that all the while she could not free herself from just this fear — the fear that you might be Larsan!”

Mathilde, who had f

allen half fainting into a chair, gathered strength enough to start up and to protest against the words with a frightened, despairing gesture.

As for M. Darzac, his face was a picture of hopeless anguish. He sank upon a couch and said in a voice so low that it was scarcely audible and so full of wretchedness that it pierced our hearts:

“And could you have thought that, Mathilde?”

His wife dropped her eyes and spoke not a word.

Rouletabille, still merciless, continued:

“When I recall all the acts of Mme. Darzac after your return from San Remo, I can see now in each one of them an expression of the terror which she experienced from her fear that she should allow the secret of her suspicion and her constant agony to escape her. Ah, let me speak, M. Darzac! Everything must be said — everything must be explained here and now if there is to be peace in the future! We are about to clear up the situation. To go on then, there was nothing natural or happy in Mlle. Stangerson’s behavior. The very eagerness with which she assented to your desire to hasten the marriage ceremony proved the longing which she felt to definitely banish the torment of her soul. Her eyes — I remember it now! — used to say at that time — how often and how clearly! ‘Is it possible that I continue to see Larsan everywhere, even in the face of the man who is at my side, who is going to lead me to the altar and to take me away with him?’

“From the moment of your return from the South until the apparition at the railroad station, monsieur, she lived in the most utter misery. She was already crying for help — for help against herself — against her thoughts — and, perhaps, even against you! But she dared not reveal her thought to any person because she dreaded that any confidant might say to her—”

And Rouletabille leaned over and said in M. Darzac’s ear, not so low that I could not hear, but so softly that the words did not reach Mathilde: “Are you going mad again?”

Then, lifting his head again, he continued:

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

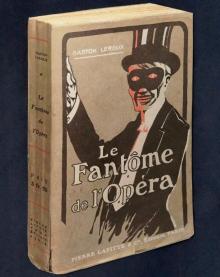

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)