- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room Page 5

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room Read online

Page 5

At that moment, my young friend came out of the Chateau followed by Darzac. As incredible as it seemed, I saw, at a glance, that they appeared to have become the best of friends.

“We’re going to see the Yellow Room. Come with us, Sainclair,” Rouletabille said. “And since we’ll be spending the whole day here, we’ll have lunch somewhere in the area…”

“Please, allow me to be your host at the Chateau, gentlemen,” offered Darzac.

“Thank you, but no,” replied Rouletabille. “We’ll eat at the Auberge du Donjon.”

“I’m afraid you’ll fare rather badly there. You won’t find anything—”

“Do you think so? Because I do hope to find something there,” said Rouletabille. “After lunch, we’ll set to work again, then I’ll write my article. Sainclair, would you be kind enough to deliver it to L’Epoque for me?”

“Won’t you come back to Paris with me?”

“No. I plan to stay here.”

I looked at Rouletabille, but he was quite serious, and Darzac did not appear in the least surprised.

We were walking by the old tower when we heard wailing from inside. It was the caretakers.

“Why have those people been arrested?” asked Rouletabille.

“Well, I’m partly responsible for that,” said Darzac. “I happened to tell the Investigating Magistrate yesterday that I thought it was strange that the caretakers had time to hear the gunshots, dress themselves, and run all the way from their lodge to the pavilion in two minutes, which is the time that elapsed between the firing of the shots and when they met Père Jacques.”

“That is suspicious indeed,” said Rouletabille. “And you say that they were fully dressed?”

“That’s what’s so strange. They were—warmly even. There was nothing missing. The woman wore clogs, but Monsieur Bernier had had time to lace his boots. Now, they claim that they went to bed at 9 p.m., like every other day. But, this morning, the Investigating Magistrate brought with him a revolver of the same caliber as the one found in the room. He obviously didn’t want to use the real gun, which is being held in evidence. He asked his clerk to fire two blank shots inside the Yellow Room, with the doors and the windows closed. We stood with him in the caretakers’ lodge, and yet we heard nothing, not a sound. Therefore, the Berniers must have lied, no doubt about it! They must have already been waiting near the pavilion for something! They’re not accused of being the authors of the crime, but they could very well be accomplices. That’s why Monsieur de Marquet had them arrested.”

“Ridiculous! If they’d been involved,” said Rouletabille, “they would have arrived all disheveled—or better yet, not shown up at all. When people throw themselves into the arms of the Law with such obvious proof of wrongdoing, you can be pretty sure they’re innocent. Besides, I don’t believe there are any accomplices in this affair.”

“Then, what were they doing there, fully dressed at midnight? Why won’t they explain themselves?”

“They must have some reason for their silence. We’ve got to found out what it is, because, even if they’re innocent, it might still be relevant to the investigation. Everything that took place on that night is important.”

We had just crossed an old bridge over the moat and entered the section of the grounds called the Oak Grove. The oaks here were centuries-old. Autumn had already shrivelled their golden leaves, and their high branches, dark and twisted, looked like the horrid hair, made up of writhing snakes, that the ancient sculptors gave to the head of the Medusa. This place, which Mademoiselle Stangerson found cheerful during the summer—her stated reason for staying at the pavilion—now seemed to us sad and funereal.

The grounds were dark and muddy from the recent rains and rotting leaves; the trunks of the trees were just as murky, and even the skies above our heads looked as if they were in mourning, filled as they were with great, dark clouds. It was in this somber and desolate place that we first saw the white walls of the pavilion.

It was an odd-looking building, with no visible windows from where we stood. The only opening was a small single door. It looked like a tomb, a vast mausoleum buried in the midst of a thick forest.

As we got nearer, we were able to make out its surroundings. It received all the light it needed from the south, that is to say, from the open woods on the other side of the grounds. Once that small door was closed, Professor Stangerson and his daughter were ideally secluded to complete their work and their dreams.

I shall now insert here a plan of the pavilion. It had a ground floor, which was reached by a few steps, and above it was a high-ceilinged attic, with which we don’t need to concern ourselves. It is only the plan of the ground floor that I unclude here.

This plan was drawn by Rouletabille himself, and I have assured myself that there is nothing missing, not a single line, nor any significant detail that might otherwise help to find a solution to the baffling problem that had been laid out before the police.

With this plan, and the accompanying explanations, my readers will know just as much as Rouletabille and I did when we entered the pavilion for the first time.

They may now ask themselves as we did: How did the perpetrator manage to escape from the Yellow Room?

1. The Yellow Room, with its one window and its single door opening into the laboratory.

2. The Laboratory, with its two large, barred windows and its two doors, one leading to the vestibule, the other to the Yellow Room.

3. The Vestibule, with its unbarred window and the door opening onto the grounds.

4. The Lavatory.

5. Stairs leading to the attic.

6. The large and only fireplace in the pavilion, used in the experiments being conducted in the laboratory.

Before climbing the three steps leading up to the door of the pavilion, Rouletabille stopped and asked Darzac point blank:

“What do you think was the motive for the attack?”

“As far as I’m concerned, Monsieur, I have no doubt about that,” the Sorbonne Professor replied, showing great distress. “My fiancée’s attacker was a savage brute, a blood-thirsty lunatic. The deep scratches on her chest and throat show that he intended to ravage and kill her. The doctor who examined them yesterday concluded that they were from the same hand which left its bloody imprint on the wall; a large man’s hand—much too big to fit into my gloves, you will note,” he added with a wan and somewhat bitter smile.

“Couldn’t that bloody handprint have been Mademoiselle Stangerson’s?” I interrupted. “When she fell, she might have leaned against the wall and, sliding down, enlarged the impression?”

“There wasn’t a drop of blood on her hands when they found her,” replied Darzac.

“Then, that tells us for a fact,” I said, “that it was Mademoiselle Stangerson who used Père Jacques’s revolver and hit her attacker in the hand. Therefore, she must have been fearful of something—or somebody.”

“Very likely.”

“Do you suspect anyone?”

“No,” replied Darzac, looking at Rouletabille.

Rouletabille then said to me:

“I have to tell you, my dear Sainclair, that the investigation is a little more advanced than our cagey Magistrate, Monsieur de Marquet, chose to tell us. He not only knew that Mademoiselle Stangerson had defended herself with Père Jacques’ gun, but he also knew the nature of the weapon that was used against her. Monsieur Darzac told me that it was a sheep-bone. Why is Monsieur de Marquet being so secretive about it? Perhaps to facilitate the Sûreté’s inquiries? Or he perhaps believes that the owner of the ‘murder weapon,’ as it were, will be found among the wretches of the Paris underground, because they often use that crude and brutal tool? Who can tell what goes on inside an Investigative Magistrate’s mind?” concluded Rouletabille with contemptuous irony.

“So they found the sheep-bone inside the Yellow Room?” I asked.

“Yes, Monsieur,” replied Darzac. “At the foot of the bed. But I beg of you to not say

anything about it to anyone. Monsieur de Marquet insisted that it should remain totally confidential.” (I made a gesture of assent.) “It was a large sheep-bone, the top of which, or rather the joint, was still red with the blood of my fiancée. It was an old bone, which may have been used for other crimes. At least, that’s what Monsieur de Marquet believes. He thinks he saw not only Mathilde’s blood on it, but older stains of dried blood, which might be the evidence of earlier crimes. He’s sent to the crime laboratory in Paris to be analyzed.”

“A sheep-bone in the hand of a skilled assassin is a deadly weapon indeed,” said Rouletabille, “more versatile and dangerous than a hammer.”

“No more so than in this case,” said Darzac, glumly. “That bone was used to hit Mathilde on the forehead, and the joint exactly fit the wound inflicted. I think that the blow would have killed her, if she hadn’t shot at the murderer. Wounded in the hand, he dropped the sheep-bone and fled. Unfortunately, the blow had already been struck, and Mademoiselle Stangerson was well stunned, after having been almost strangled. If she had succeeded in wounding her attacker with her first shot, she might have escaped that blow, but she used her gun too late. Her first shot went astray and hit the ceiling instead. It was only the second shot that hit her assailant.”

Having said this, Darzac knocked at the door of the pavilion. I must confess that I was quite excited at the idea of being able to inspect the room where the crime had been committed. I was trembling with impatience and, despite the interest I felt for the story of the sheep-bone, I couldn’t wait for the door to open.

Finally, it did. A man, whom I assumed was Père Jacques, stood on the threshold.

He appeared to be well over 60. He had a long white beard and white hair; he wore a béret, a well-used, brown corduroy jacket, and clogs on his feet. He looked grumpy at first, but his face lit up as soon as he saw Darzac.

“These are friends of mine, Père Jacques,” said our guide. “Is anyone else here?”

“I’m not supposed to let anyone in,” said the old man, “but, of course, that doesn’t apply to you, Monsieur Robert. Besides, the police have already seen everything there is to see here. God knows they made enough drawings and took enough statements!”

“Excuse me, Père Jacques, but might I ask you a question before we proceed,” said Rouletabille.

“What is it, young man? If I can answer it, I shall”

“Did your mistress wear her hair in plaits, that night? You know what I mean, wrapped over her forehead?”

“No, Monsieur. My mistress never wore her hair in that fashion, not on that day or any other. She had her hair pulled up, as usual, so that her beautiful forehead could be seen—pure as that of an unborn child!”

Rouletabille grunted an acknowledgment and began to examine the door, finding that it shut automatically. He determined that it couldn’t remain ajar, and that one had to have a key to open it. Then, we entered the vestibule, a small, well-lit room with a red-tiled floor.

“Ah! This is the window through which the murderer is supposed to have escaped!” said Rouletabille.

“That’s what they keep saying, Monsieur,” said Père Jacques, “but if he had gone that way, we would have certainly seen him. We’re not blind, the Professor and I, and neither are the Berniers, who’ve been arrested. Why haven’t they arrested me, too, on account of my revolver?”

Rouletabille had already opened the window and was now examining the shutters.

“Were these closed at the time of the crime?”

“Yes! Fastened with the iron catch, from the inside,” said Père Jacques. “And yet, I’m sure the villain just walked through them like a ghost!”

“Were there any blood stains?”

“Yes, on the stones outside… But who did they belong to? That’s the question!”

“Ah!” said Rouletabille, “I see some footprints on the path—the ground was very damp and preserved them. I’ll look into this later.”

“Nonsense!” interrupted Père Jacques. “The murderer can’t have gone that way.”

“Which way did he go, then?”

“How would I know?”

Rouletabille looked at everything, smelled everything. He went down on his knees and rapidly examined every one of the vestibule tiles. Père Jacques went on:

“Ah! You won’t find anything there, Monsieur. No one has found anything so far. And now, it’s all dirty! Too many folks have been trampling all over the place. They won’t let me wash the floor now, but on the day of the crime, I’d washed it thoroughly, I, Père Jacques, and if the murderer had crossed my clean floor with his big, dirty boots, I’d certainly have noticed it! After all, he left plenty footprints in Mademoiselle’s room.”

Rouletabille rose.

“When was the last time you said you washed these tiles?” he asked, and he looked at Père Jacques carefully.

“Why—as I’ve just told you—on the day of the crime, around 5:30 p.m., when Mademoiselle and the Professor were taking a walk before they had dinner here, in the laboratory. The next day, when the Investigating Magistrate came, he could see all the footprints on the floor, clear as ink on paper. Well, he didn’t find any traces of a stranger, either in the laboratory, or in the vestibule. Both were clean as a whistle. But since they did find some footprints outside this window, Mademoiselle’s attacker could have gone through the ceiling of the Yellow Room into the attic, then cut his way through the roof and then dropped to the ground outside the vestibule window. Except that there’s no hole in the ceiling of the Yellow Room or in the roof—that’s for certain! So, you see, we’ve got nothing—absolutely nothing! My guess is that we won’t ever find out the truth! This mystery is of the Devil’s own making.”

Rouletabille got down on his knees again in front of the door leading to a small lavatory located at the back of the vestibule. He remained in that position for a minute or so.

“Well?” I asked him when he got up.

“Oh! Nothing very important… A small drop of blood,” he replied.

Then, he turned towards Père Jacques again.

“When you were washing the laboratory and the vestibule floors, was the vestibule window open?” he inquired.

“I had just opened it because I had lit some charcoal for the Professor in the laboratory furnace, and, as I had used some old newspapers to start the fire, there was a bit of smoke, so I opened both the windows in the laboratory and this one, to create a draft. After the smoke cleared, I shut the windows in the laboratory, but I left this one open when I went out to get some rags at the Chateau.

“When I returned, it was about 5:30 p.m. as I told you. I then washed the floors. After I finished, I went back to the castle again, leaving the window open. When I returned to the pavilion for the last time, it had been closed and the Professor and Mademoiselle were already busy at work in the laboratory.”

“So the Professor or Mademoiselle Stangerson had probably shut the window?”

“Probably, yes.”

“Did you ask them?”

“No.”

After a close examination of the little lavatory and the staircase leading up to the attic, Rouletabille—to whom we seemed to no longer exist—entered the laboratory. I followed him, in a state of growing excitement. Meanwhile, Darzac had closely watched all of my friend’s movements.

My eyes were drawn at once to the door of the Yellow Room. It was, in fact, leaning against the door frame, having been broken off its hinges. The efforts of the two men who had crashed through it on the night of the crime had severely damaged it.

Rouletabille, who went about his business methodically, studied the laboratory in silence. It was a big and well-lit room with two very large windows—almost bays—protected by strong iron bars, looking out upon the neighboring woods. Through an opening in the trees, one had a wonderful view of the entire valley, all the way to the town of Epinay, which must have been visible on a clear day. On that day, however, there was only mud on the ground, soo

ty skies—and blood waiting for us in the Yellow Room!

One side of the laboratory was entirely taken up by a large fireplace, crucibles, ovens, and other implements required for chemical experiments. Next to it was a long table loaded haphazardly with beakers, test tubes, notebooks, filing boxes, measuring instruments, batteries and some kind of an electrical apparatus, which Darzac told us, was used by the Professor “to demonstrate the dissociation of matter under the action of electrical power.”

Along the other wall were cabinets, plain or with glass-doors, through which one could see microscopes, special photographic equipment, and a large quantity of crystals.

Rouletabille was now ferreting inside the fireplace. He searched the crucibles and, suddenly, drew himself up. He held up a piece of half-charred paper in his hand. He walked toward the window where we stood, chatting.

“Will you please keep this paper for me, Monsieur Darzac?” he said.

I loked at the scorched piece of paper which Darzac had just taken from Rouletabille, and read the only words that remained legible on it:

Presbytery … lost none … charm, nor … gard… its glow.

And beneath that was a date: October 23.

This was the second time that I had seen, or heard, those apparently meaningless words, and I saw that they produced the same frightful effect on Darzac. His first reaction was to look at Père Jacques, but the old man was busy at the other window and hadn’t noticed anything. Then, the Sorbonne Professor opened his wallet and, his hand shaking, put the piece of paper inside, sighing: “My God!”

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

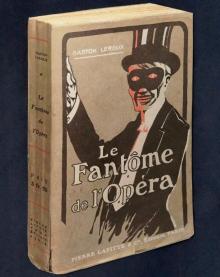

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)