- Home

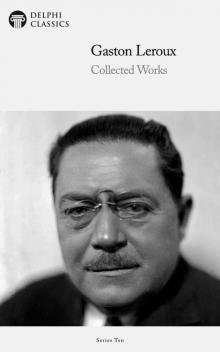

- Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Page 49

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

Page 49

Rouletabille was examining the iron bars and heavy lid which closed the shaft, but his manner was distrait and discouraged. After he had finished what seemed to be a very careless inspection he stretched himself out on the ground as if it were a couch in which he was trying to get some rest. Turning once more to his hostess, he said in the same low voice:

“And what will you tell the police when they get here?”

“Everything!”

Mrs. Rance fairly snapped out the word between her teeth, her eyes flashing fire. Rouletabille shook his head sorrowfully and closed his eyes. He seemed utterly exhausted and vanquished. Robert Darzac touched him on his shoulder. M. Darzac wanted to search through the Square Tower, the Tower of the Bold, the New Castle — all the dependencies of the fort from which no one could have made his escape, and where, therefore, the assassin must still be concealed. The reporter shook his head drearily, and said that it would be of no use. Rouletabille and I knew only too well that any search would be in vain. Had we not made a search at the Glandier after the phenomenon of the dissolution of matter, for the man who had disappeared in the inexplicable gallery? No, no! I had learned that there was no use in looking for Larsan with one’s eyes.

A man had been murdered just behind our backs. We had heard him cry out when the blow struck him down. We had turned around and had seen nothing except the daylight. To see clearly, it was better to close the eyes as Rouletabille was doing at this moment.

And when he opened them, he was another man! A new energy animated his features. He stood erect as though he had thrown off a weight. He clenched his fist and raised it toward the heavens.

“That is not possible!” he cried. “Or there is no more good in reasoning.”

And he threw himself on the ground, creeping on his hands and knees, his nose to the earth, like a hound following the scent, going round the body of poor Bernier and around Mere Bernier, who had blankly refused to leave her husband — around the shaft — around each of us. He moved about like a pig, nosing its nourishment out of the mire, and we all stood still, looking at him curiously and half in alarm. Suddenly he started to his feet, almost white with dust and uttered a shout of triumph as though he had found Larsan himself in the gravel. What new victory did the boy feel that he had achieved over the mystery? What had given this new firmness to his step and steadiness to his glance? What had given back to him the strength of his voice? For when he addressed M. Robert Darzac his tones were full of vigor and resolution.

“It’s all right, Monsieur! Nothing is changed!”

And, turning to Mme. Edith —

“There is nothing more to do, Madame, except to wait for the police. I hope that they will not be long.”

The unhappy woman shuddered. I knew that she was again struck with mortal fear.

“Yes, let them come!” she cried, taking my arm. “And let them attend to everything! Let them think for us! Whatever may happen, let it come as soon as it will.”

Attracted by the sound of voices we looked around and saw Pere Jacques approaching, followed by two gendarmes. It was the brigadier of la Mortola, who, summoned by Prince Galitch, had hurried to the scene of the crime.

“The gendarmes! the gendarmes! They say that murder has been done!” exclaimed Pere Jacques, who as yet knew nothing of what had happened.

“Be calm, Pere Jacques!” exhorted Rouletabille, and when the old man, panting and breathless, drew near to the reporter, the latter said to him in low tones:

“Nothing is changed, Pere Jacques!”

But Pere Jacques was gazing at Bernier’s body.

“Only one more dead man!” he sighed. “This is Larsan’s work again!”

“It is the work of destiny!” answered Rouletabille.

Larsan and destiny — both were as one. But what did Rouletabille mean by his “Nothing is changed,” if not that, despite the incidental murder of Bernier, everything which we dreaded, which made us shudder and which we had no understanding of, continued just as before?

The gendarmes were busy examining the body and chattering over it in their uncomprehensible jargon. The brigadier informed us that they had telephoned to the Garibaldi Tavern, a few steps away, where at this moment the delegato, or special commissioner, stationed at Vintimille, was even now breakfasting. The delegato would have power to begin the investigation, which would be continued when the examining magistrate had been notified.

The delegato arrived. It was easily to be seen that he was enchanted, even though he had not had the time to finish his repast. A crime! actually a crime! And in the Château of Hercules. He was fairly radiant; his eyes shone. He was full of business, full of importance. He ordered the brigadier to station one of his men at the gate of the château with directions to permit no person to pass in or out. Then he knelt down beside the body while a gendarme, despite her protestations and tears, led Mere Bernier away to the Square Tower, where her groans sounded louder than ever. The delegato examined the wound and said in very good French:

“That was a magnificent stroke!”

The man was enchanted. If he had had the assassin under arrest, he would assuredly have paid him his compliments. He looked at us. Then he looked at us again. Perhaps he was seeking among us for the criminal to tell him of his admiration. At last he rose from his knees.

“And now how did all this happen?” he asked encouragingly, smacking his lips as though in the anticipation of hearing a story of thrilling interest. “It is terrible!” he added— “terrible! In the five years that I have been delegato, we have never had a murder. Monsieur the examining magistrate — .” Here he checked himself but we knew well what he had been on the point of saying: “Monsieur the examining magistrate will be very much pleased.” He brushed away the white dust which covered his knees, wiped the perspiration from his forehead and repeated “It is terrible!” his Southern accent seeming to grow stronger. And at that moment, he noticed in a new arrival who entered the court, a doctor from Mentone who had come to continue his treatment of Old Bob.

“Ah, doctor, I am glad that you are here! Just look at this wound and tell me what you think of such a knife stroke. But be as careful as possible about changing the position of the corpse before the arrival of the examining magistrate.”

The doctor sounded the depth of the wound and gave us all the technical details which we could desire. There was no doubt about it at all. It was a truly magnificent stroke of the knife which had penetrated from high to low in the cardiac region and the point of the knife had certainly opened a ventricle. During the colloquy between the delegato and the doctor, Rouletabille never took his eyes off Mme. Edith, who was still clinging to my arm as though she knew that I was her only refuge. Her eyes fell before the eyes of Rouletabille which seemed to hypnotize her and to command her to be silent. But I knew that she was trembling with the desire to speak.

At the request of the delegato, we all entered the Square Tower. We took our places in Old Bob’s sitting room, where the inquest was to be held and where each of us in turn recounted what we had seen and heard. Mere Bernier was first questioned, but little or nothing could be gained from her testimony. She declared that she knew nothing about anything. She had been in Old Bob’s bedroom, attending to the needs of the injured man, when we had rushed madly into the room. She had been with Old Bob for an hour, having left her husband in the lodge of the Square Tower, ready to work at making a rope.

It was a curious fact, but I was less interested at that moment in what was going on under my eyes than in what I could not see and yet knew that I expected.

Would Edith speak? She was looking out of the open window, her lips compressed, her brows drawn. A gendarme was standing near the corpse over the face of which a handkerchief had been laid. Edith, like myself, was paying very little heed to what was going on inside the room. Her eyes were fixed upon Bernier’s body.

An exclamation from the delegato struck upon our ears. The further the evidence of the witnesses progressed, the

greater became the amazement of the Commissioner, and the more and more inexplicable he found the crime. He was on the point of finding it impossible that it should have been committed at all, when it came Mme. Edith’s turn to be interrogated.

They questioned her. Her lips were already opened to answer the first question when Rouletabille’s quiet voice was heard:

“Look at the end of the shadow of the eucalyptus.”

“What is there at the end of the shadow of the eucalyptus?” demanded the delegato.

“The weapon with which the crime was committed,” replied the reporter.

He jumped out of the window to the court and picked up from the bloody stones a sharp, shining piece of flint. He brandished it in our eyes. We all recognized it. It was “the oldest dagger of the human race.”

CHAPTER XIX

IN WHICH ROULETABILLE ORDERS THE IRON DOORS TO BE CLOSED

THE WEAPON BELONGED to Prince Galitch, but there was no doubt in the mind of any one of us that it had been stolen by Old Bob, and we could not forget that with his latest breath Bernier had accused Larsan of being his assassin. Never had the image of Old Bob and that of Larsan been so inextricably confounded in our restless spirits as since Rouletabille had found “the oldest dagger known to the human race” dripping with the blood of Bernier. Mme. Edith had at once realized that henceforth the fate of Old Bob lay in the hands of Rouletabille. The latter had only to say a few words to the delegato relative to the singular incidents which had accompanied the fall of Old Bob into the cave in the Grotto of Rorneo and Juliet, enumerating the reasons which had given occasion for fear that Old Bob and Larsan were one and the same, and, finally, repeating the accusation made by the last victim of Larsan, in order to fix the suspicions of the delegato firmly upon the wigged head of the professor of geology. And, therefore, Mme. Edith, who in her filial affection had not ceased to believe that the man who lay on his bed in the Square Tower was really her uncle, had begun to imagine, thanks to the bloody weapon, that the invisible Larsan had woven so strong a web of circumstantial evidence around Old Bob that it could scarcely be broken, with the design, doubtless, of making the old man suffer the punishment for the wretch’s own crimes and also the dangerous weight of his personality. Mme. Edith trembled for Old Bob and for herself. She trembled with fear, like an insect in the center of the web in which it has lost itself — this mysterious web woven by Larsan, attached by invisible threads to the old walls of the Château of Hercules. She felt as though if she were to make a sudden movement — to say anything even — both she and her uncle would be lost, and that some horrible beast of prey awaited only this signal to spring upon and devour her. So she who had been so anxious to speak out stood silent and when Rouletabille was called upon, it was her turn to fear. She told me afterward of her state of mind at this time and she acknowledged to me that her terror of Larsan had reached such a pitch as even we, who had known so much of his evil power already, had never experienced. This were wolf whose name she had so often heard spoken in accents of horror which had made her smile, had begun to interest her, when she learned of the events of the Yellow Room, because of the impossibility of the police discovering the manner of his exit. Her interest had increased when she had heard the story of the attack of the Square Tower because of the impossibility of anyone’s explaining how Larsan could have entered; but, now — now, in the full glare of the noonday sun, Larsan had killed a man almost under her own eyes, and within a radius in which there was at the time only herself, Robert Darzac, Rouletabille, myself, Old Bob and Mere Bernier, each and every one of them far enough away from the body so that not one could have struck Bernier down. And Bernier had accused Larsan! Where was Larsan? In whose body? — according to the reasoning which I had set forth to her myself in telling her the story of the “inexplicable gallery”? She had been under the arch with Darzac and myself, standing between us, with Rouletabille in front of us, when the death cry had resounded at the end of the shadow of the eucalyptus tree — that is to say, at least, seven meters away. As to Old Bob and Mere Bernier, they had not been separated; the one had watched over the other. If she placed them outside the realms of possibility, there was no one left to kill Bernier. Not alone this time was everyone ignorant how he had departed but also of how he had been present. Ah, she understood now that when one thought of Larsan there were moments in which one shivered to the marrow of one’s bones!

Nothing! Nothing anywhere around the corpse but the stone knife which Old Bob had stolen! It was frightful — it was reason enough for us to think of everything — to imagine everything!

She read the certainty of this conviction in the eyes and in the manner of Rouletabille and of Robert Darzac. But she understood as soon as the young man began speaking that he seemed to have no other end in view than to save Old Bob from the suspicions of the authorities.

Rouletabille was given a seat between the delegato and the examining magistrate who had arrived while Mme. Edith had been testifying, and he gave his evidence (or rather, reasoned the matter out) holding the “oldest knife known to the human race” in his hand. It seemed definitely established that the guilty person could have been no other than one of the living men and women who were near the dead man and whom I have enumerated above, when Rouletabille proved with a logical accuracy that overwhelmed the examining magistrate and plunged the delegato into despair that the deed could only have been committed by the dead man himself. The four persons at the postern gate and the two persons in Old Bob’s room had each been looking at the others and had not lost sight of each other while someone was killing Bernier a few steps away, so it was impossible to believe that the killing could have been done by any other than the victim.

To this the examining magistrate, greatly interested, replied by inquiring whether any of us had reason to suspect any motive for suicide on the part of Bernier, to which Rouletabille answered that the supposition of suicide might easily be laid aside and that of accident substituted for it. “The weapon of the crime,” as he called ironically the “oldest knife known to the human race,” testified to the truth of this theory by its presence. Rouletabille declared that there would be no chance of an assassin meditating the commission of a murder with an old piece of stone as an instrument. And still less could one believe that Bernier, if he had resolved upon suicide, would not have found another means toward his end than the one which had been used. But if, on the contrary, that stone, which might have attracted his attention by its strange form, had been picked up by Pere Bernier, and if he had happened to slip and fall while holding it in his hand, everything would be explained and very simply. Pere Bernier, undoubtedly, must have thus unfortunately fallen upon this triangular flint which had pierced his heart.

After Rouletabille had stated this hypothesis, the physician was recalled, the wound examined once more and confronted with the fatal object from which the scientific conclusion was reached that the wound was made by the object. From this to the theory of accident, as stated by Rouletabille, there was only a step. The judges spent six hours in clearing up the matter — six hours during which they questioned us without weariness but without result.

As to Mme. Edith and your humble servant, after some futile and useless questions, asked while the doctors were at the bedside of Old Bob, we were allowed to leave the room and we went to sit in the little parlor just outside the bedroom and were there when the magistrates were ready to depart. The door of this parlor which opened upon the corridor of the Square Tower had not been closed. We could hear the sobs and groans of Mere Bernier, who was watching beside the body of her husband which had been carried into the lodge. Between this body and the wounded man, the injury to one as inexplicable as the death of the other, the situation of both Mrs. Rance and myself had become extremely painful, in spite of Rouletabille’s efforts, and all the terrors which we had experienced before grew pale and simple before the thought of what might be yet to come. Edith suddenly seized me by the hand and cried out:

“Do not leave me! I beg of you, don’t leave me! I have only you left. I do not know where Prince Galitch is — I do not know anything about my husband. That is what makes this so horrible. Arthur sent me a message, saying that he was going in search of Tullio. He does not know even yet that Bernier has been murdered. Has he found the ‘hangman of the sea’? It is from this man — from Tullio now that I expect the truth! And not a word has come! It is horrible!”

As she took my hand so confidingly and held it for a moment in her own, I felt that I was for Mme. Edith with all my heart and soul and I assured her that she might rely upon my devotion. We murmured a few words of trust and eternal fidelity to each other in low voices while there in the corridor we could see, passing back and forth, the dark forms of the emissaries of justice, now preceded, now followed by Rouletabille and M. Darzac. Rouletabille never failed to cast a glance in our direction every time he had the opportunity. The window remained open.

“Ah, he is watching us!” exclaimed Mme. Edith. “Why is that, I wonder? Probably we are in his way and M. Darzac’s when we remain here. But, whatever may happen, we shall not stir, shall we, M. Sainclair?”

“You ought to be grateful to Rouletabille,” I ventured to remind her; “for his intervention and his silence relative to the ‘oldest knife known to the human race.’ If the officers had learned that this stone dagger belonged to your uncle, Bob, what could have hindered them from placing him under arrest? Or if they knew that Bernier in dying had accused Larsan of his murder, the story of the accident would have found very little credence.”

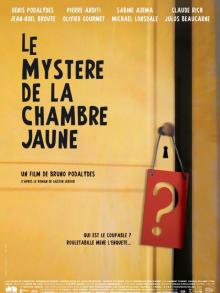

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

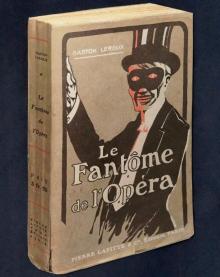

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)