- Home

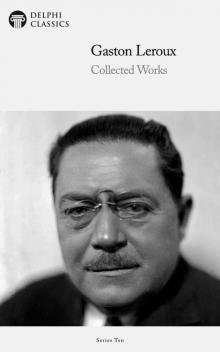

- Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Page 40

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

Page 40

I desire here, by way of parenthesis, to ask the pardon of the reader for the mathematical precision with which for the last few pages, I have enumerated our every act and movement, but I will assure him, once and for all, that even the smallest circumstances have in reality a considerable importance, for everything which we did at this time was done, though alas, we did not guess it, on the brink of a precipice.

As Old Bob seemed to be in a churlish humor, we left him — that is, Rouletabille and myself did. M. Darzac remained gazing at his spoiled drawing, but thinking, doubtless, of altogether different things.

As we went out of the Round Tower, Rouletabille and I raised our eyes to the sky which was rapidly becoming covered with great, black clouds. The tempest was near at hand. In the meantime, the air seemed to grow more and more stifling.

“I am going to lie down in my room,” I said. “I can’t stand any more of this. Perhaps it may be cooler there with all the windows open.”

Rouletabille followed me into the New Castle. Suddenly, as we reached the first landing of our winding staircase, he stopped me:

“Ah,” he said in a low voice; “she is there!”

“Who?”

“The Lady in Black. Can’t you smell the perfume?”

And he hid himself behind a door, motioning me to continue without waiting for him. I obeyed.

What was my amazement in opening the door of my room to find myself face to face with Mathilde!

She uttered a low cry and disappeared in the shadow, gliding away like a surprised bird. I rushed to the staircase and leaned over the balustrade. She swept down the steps like a ghost. She soon gained the ground floor and I saw below me the face of Rouletabille, who, leaning over the rail of the first landing, looked at her, too.

He mounted the steps to my side.

“Oh, my God!” he cried. “What did I tell you! Poor, poor soul!”

He seemed to be in the greatest agitation.

“I asked M. Darzac for eight days!” he went on. “But this thing must be ended in twenty-four hours or I shall no longer have strength to act.”

He entered my room and threw himself into a chair as if exhausted. “I am smothering!” he moaned. “I can’t breathe!” He tore his collar away from his throat. “Water!” he entreated. “Water!”

I started to fetch some, but he stopped me.

“No — I want the water from the heavens! I must have it!” and he waved his hands toward the dark skies from which huge drops were slowly beginning to fall.

For ten minutes he remained stretched out in the chair, thinking. What surprised me was that he asked no question or uttered no conjecture as to what the Lady in Black had been seeking in my room. I would not have known how to answer, if he had done so. At length, he rose.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“To take the guard at the postern.”

He would not even come in to dinner and sent word to have some soup brought out to him as though he were a soldier. The dinner was served in la Louve at half past eight. Darzac, who came to the table from Old Bob’s workroom, said that the latter refused to dine also. Mme. Edith, fearing that her uncle might be ill, went immediately to the Round Tower. She would not even allow her husband to accompany her — indeed, she seemed to be much out of humor with him.

The Lady in Black came in on the arm of her father. She cast on me a look of sorrowful reproach which disturbed me greatly. Her eyes seemed never to wander from me.

It was a gloomy meal enough. No one ate much. Arthur Rance looked every moment in the direction of the Lady in Black. All the windows were open. The atmosphere was suffocating. A flash of lightning and a heavy clap of thunder came in rapid succession — and then, the deluge! A sigh of relief issued from our overcharged breasts. Mme. Edith reappeared just in time to escape being drenched by the furious rain which beat down like cannon balls upon the peninsula.

The young woman told us in excited tones and with her hands clasped, how she had found Old Bob bending over his desk with his head buried in his hands. He had refused to have anything to say to her. She had spoken to him affectionately and he had treated her like a bear. Then, as he had obstinately held his hands to his ears, she had pricked one of his fingers with a little pin set with rubies which she used to fasten the lace scarf which she wore in the evening over her shoulders. Her uncle, she said, had turned upon her like a madman, had snatched the little pin from her and thrown it upon the desk. And then he had spoken to her— “brutally, rudely as he had never done before in his life!” she ejaculated. “Get out of here and leave me alone!” was what he had said to her. Mme. Edith had been so much pained that she went out without saying a word, promising herself, however, that she would not soon set foot again in the Round Tower. But she had turned her head for one last look at her old uncle and had been almost struck dumb by what she saw.

The “oldest skull in the history of the human race” was upon the desk, and Old Bob, a handkerchief stained with blood in his hand, was spitting in the skull. He had always treated it with the most severe respect and had insisted that others should do the same. Edith had hurried away, almost frightened.

Robert Darzac reassured her by telling her that what she had taken for blood was only paint and that Old Bob’s skull had been spattered by the paints which had been used in the wash drawing.

I left the table to hurry out to Rouletabille and also to escape from Mathilde’s glances. What had the Lady in Black been doing in my bedroom? I was not to wait long to know!

When I started out the thunder was pealing loudly and the rain falling with redoubled force. It took me only one bound to reach the postern. No Rouletabille was there! I found him on the terrace B”, watching the entrance to the Square Tower and receiving the full strength of the storm at his back.

I entreated him to take shelter under the arch.

“Leave me alone!” he said impatiently. “Leave me alone. This is the deluge. Ah, how good it is! how good — all this anger of the heavens! Have you ever had a desire to roar with the thunder? I have — and I am roaring now. Listen, while I cry out — alas! alas! alas! My voice is stronger than the thunder!”

And he plunged into the darkness making the shadows resound with his savage clamors. I believed this time that he had surely gone mad! But in my heart I knew that the unhappy lad was breathing forth in these indistinct articulations of frightful anguish the misery that burned him, and which he was constantly trying to hinder from burning up the heart and the soul in his body — the misery of being the son of Larsan.

I turned helplessly and as I did so, I felt a hand seize my wrist and a dark form cried out to me above the tempest:

“Where is he?”

It was Mme. Darzac who was also seeking Rouletabille. A new peal of thunder burst and we heard the boy in his mad delirium hurling wild shouts of defiance to the heavens. She heard him. She saw him. We were drenched with water from the rain and the breaking of the sea on the terrace. Mme. Darzac’s clothing clung around her like a rag and her skirt dripped as she walked. I took the wretched woman’s arm and held her up, for I saw that she was about to fall, and at that moment, in the midst of that terrible unchaining of the elements, in that mad tempest, under this terrible downpour on the breast of the raging sea, I all at once breathed the perfume — the odor so sweet and penetrating and haunting that its fragrance has remained with me ever since — the Perfume of the Lady in Black. Ah, I understood now how Rouletabille had remembered it all these years.

Yes, it was a fragrance full of sadness — something like the perfume of an isolated flower which has been condemned to be seen by no one but to blossom for itself all alone. It was a fragrance which set such ideas as these running through my brain, although I did not analyze them at the time — a sweet, soft and yet insistent perfume which seemed to steal away my senses in the midst of this battle of the elements, as soon as I perceived it. A strange perfume! Surely it was that, for I had seen the Lady in Black hundreds of

times without noticing it, and now that I had done so, it was everywhere and above all things and I knew that the memory of it would abide with me while life should last. I understood how when one had — I will not say smelled but seized (for I do not think that everyone would have been able to catch the subtle fragrance of the perfume of the Lady in Black, any more than I myself had done before this night in which my senses seemed to have become sharpened to the keenest point) — yes, when one had seized this adorable and captivating odor, it was for life. And the heart would be perfumed by it, whether it was the heart of a son, like Rouletabille; or the heart of a lover, like M. Darzac; or the heart of a villain, like Larsan. No, no — the knowledge of it could never pass. And now, by some sudden insight, I seemed to understand Rouletabille and Darzac and Larsan and all the misfortunes which had attended the daughter of Professor Stangerson.

There in the night and the tempest, the Lady in Black called aloud to Rouletabille and he fled from us and rushed further into the night, shrieking aloud, “The perfume of the Lady in Black! The perfume of the Lady in Black!”

The unhappy woman sobbed. She drew me toward the tower. She struck with desperate hands at the door which Bernier opened to us and her weeping would have melted the heart of a stone.

I could only utter the veriest commonplaces, begging her to calm herself, although I would have given everything I had in the world to find words which, without betraying anyone, might perhaps have made her understand my own part in the sorrowful drama which was being played out between the mother and the child.

Suddenly she seemed to recover herself in some degree and she motioned me to enter the little parlor at the right which was just outside the bed chamber of Old Bob. The door stood open but there we were as much alone as we could have been in her own room, for we knew that Old Bob worked late in the Tower of Charles the Bold.

I can assure you that in my memories of that horrible night the thought of the moments which I spent in the company of the Lady in Black are not the least sorrowful. I was put to a proof which I had not expected, and it was like a blow full in the face when, without even taking time to speak of the way in which we had been treated by the elements, Mme. Darzac looked me full in the eyes and demanded: “How long is it, M. Sainclair, that you were at Trepot?”

I was struck dumb — overpowered more completely than I had been by the fury of the storm. And I felt that, at the moment when nature, wearied out, was beginning to grow more quiet, I was to suffer a more dangerous assault than that of thunderbolts or lightning flushes. I must, by my expression, have betrayed the agitation which was aroused in my mind by this unexpected remark, for I could see by her eyes as she looked at me that she was aware how deeply I was moved.

At first I made no answer: then I stammered out some disconnected words of which I remember nothing, save that they were ridiculous. It is years now since that night, but as I write I am living over the scene as if I were a spectator instead of the actor which I actually was, and as if it were even now going on in front of my eyes.

There are people who may be drenched to the skin and yet not look in the least ridiculous. The Lady in Black was one of them. Although, like myself, she had experienced the full fury of the storm, she was majestic and beautiful with her dishevelled locks, her bare neck and magnificent shoulders which, through the thin silk which clothed them seemed to have merely a light veil thrown across the flesh. She seemed to be a sublime statue, carved by Phidias from the immortal clay to which his chisel has given form and beauty. I am well aware that, even after all the years which have elapsed, my description sounds too glowing and I will not linger on the subject. But those who have known Professor Stangerson’s daughter will understand me, I think, and I desire, here, with Rouletabille near me, to affirm the sentiments of respectful admiration which filled my heart at the sight of this mother, so divinely beautiful, who, in the state of disorder to which the fearful tempest had brought her, and with her whole heart filled with agony, was endeavoring to make me break the oath that I had sworn to the lad who was my friend.

She took both my hands in hers and said in a voice which I shall never forget:

“You are his friend. Tell him, then, that he is not the only one who has suffered.” And she added with a sob which shook her whole frame:

“Why will he insist on not telling me the truth!”

I had not a word to say. What could I have answered? This woman had always seemed so cold and formal to the world in general and (as I had thought) to me in particular that it was as if I had not existed for her, and now she was laying bare her heart before me as though I were an old friend. And I had breathed the perfume of the Lady in Black.

Yes, she treated me as an old friend. She told me everything that I already knew in a few sentences as piteous and as simple as a mother’s love itself — and she told me other things which Rouletabille had kept a secret from me. Evidently the game of hide and seek could not have lasted long. The relationship between them had been guessed by the one as surely as by the other. Led by a sure instinct Mme. Darzac had resolved to take means to learn who was this Rouletabille who had saved her from death and who was of the age of her own son — and who resembled the lad whom she had mourned as dead. And since her arrival at Mentone, a letter had reached her containing the proof that Rouletabille had lied to her in regard to his early life and had never set foot in any school at Bordeaux. Immediately, she had sought the youth and had asked for an explanation, but he had hurried away without replying. But he had seemed disturbed when she spoke to him of Trepot and of the school at Eu, and the trip which we had made there before coming to Mentone.

“How did you know?” I exclaimed, betraying my secret without realizing that I was doing so.

She showed no sign of triumph at my involuntary confession, and in a few words went on to reveal to me her stratagem. That evening when I had taken her by surprise, it was not the first time that she had been in my room. My luggage bore the labels of the hotels at which we had stopped on our recent journey.

“Why did he not throw himself into my arms when I opened them to him?” she moaned. “Ah, my God! If he refuses to be Larsan’s son, will he never consent to be mine!”

As she told me her story, it seemed to me that Rouletabille had conducted himself in an atrocious fashion toward this poor woman who had believed him dead, who had mourned for him in despair, and who, in the midst of her terrible dread and mortal anguish, experienced a thrill of the keenest joy in realizing that her son was still alive. Ah, the poor mother! The evening before, he had mocked at her when she had cried out to him with all her soul that she had a son and that that son was he! He had mocked her, even while the tears had streamed down his cheeks. I could never have believed that Rouletabille could have been so cruel or so heartless — or, even, so ill-bred!

Certainly he behaved in an abominable fashion! He had told her with a sardonic smile that “he was nobody’s son — not even the son of a thief.” It was these words that had sent her flying to her room in the Square Tower and had made her long to die. But she had not found her son only to give him up so easily and she would — she must have him acknowledge her!

I was almost beside myself. I kissed her hands and entreated pardon for Rouletabille. Here was the result of my friend’s schemes to save her pain. Under the pretext of saving her from Larsan, he had plunged a knife into her heart. I felt as though I had no wish to know any more of the story. I knew too much already and I longed to run away. I hastened out of the room and called Bernier, who opened the door for me. I went out of the Square Tower, cursing Rouletabille roundly. I went to the Court of the Bold to look for him, but found it deserted.

At the postern gate Mattoni had come to take the ten o’clock watch. I saw a light in Rouletabille’s room and I hastened up the rickety stairway of the New Castle and quickly found myself outside his door. I opened it without knocking. Rouletabille looked up.

“What do you want, Sainclair?”

I t

old him all that I had heard and my opinion of him for his actions which had so deeply wounded Mme. Darzac.

“She didn’t tell you everything, my friend,” he replied, coldly. “She did not tell you that she forbade me to touch that man.”

“That is true!” I cried. “I heard her.”

“Well, what have you come here to tell me then?” he went on, roughly. “Do you know what she said to me yesterday? She ordered me to go away. She would rather die than see me take issue against my father.”

And he laughed — laughed. Such laughter, I hope not to hear again.

“Against my father! She thinks, I suppose, that he is stronger than I!”

His face was not a pleasant sight to see as he uttered the words.

But suddenly it seemed to be transformed and to glow with unearthly beauty.

“She is afraid for me!” he said, softly. “And I — I am afraid for her — only for her. And I do not know my father. And, God help me! I do not know my mother!”

At that moment the sound of a shot rang out on the night, followed by a cry of mortal agony! Ah, it was again the cry that I had heard two years ago in the “inexplicable gallery.” My hair rose on my scalp and Rouletabille tottered as though the bullet had struck himself.

And then he bounded toward the open window, filling the fortress with a despairing burst of anguish:

“Mother! Mother! Mother!”

CHAPTER XI

THE ATTACK OF THE SQUARE TOWER

I LEAPED AFTER him and threw my arms around his body, dreading what he might attempt. There was in that cry, “Mother! Mother! Mother!” such a madness of despair, a call, or rather, an assurance of coming aid so beyond the realization of human strength, that I was obliged to fear that the young fellow had forgotten that he was only a man and had not the power to fly straight out of the window of the tower and to traverse, like a bird or a flash of lightning, the black space which separated him from the crime which had been committed and which he filled with his frightful cries. Quickly, he turned on me, threw me off, and precipitated himself wildly, through corridors, apartments, stairways and courts toward the accursed tower from which had come that same death cry that we both had heard — a moment ago, and also two years before when it had resounded through the “inexplicable gallery.”

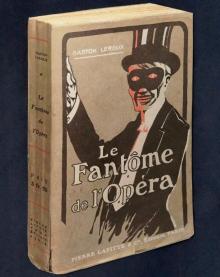

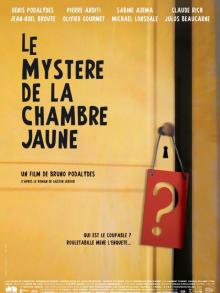

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)