- Home

- Gaston Leroux

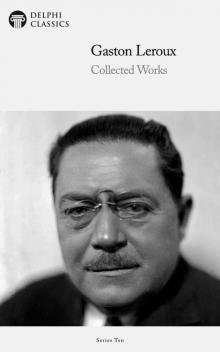

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Page 37

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

Page 37

(1) The Morning.

The day, almost from the rising of the sun, was intolerably hot and the hours on guard were almost overpowering. The sun was as torrid as in the heart of Africa and it would have blinded us to keep watch over the waters which burned like a sheet of steel, brought to a white heat, if we had not been furnished with eyeglasses of smoked glass, without which it is difficult to pass the season of departing winter in this part of the country.

At nine o’clock, I came down from my room and went to the postern and entered the room which we had styled “the hall of counsel” to relieve Rouletabille of his guard. I had no time to say a single word to him before M. Darzac appeared, following almost upon my heels, and announcing that he had something very important to communicate to us. We inquired anxiously the cause of his agitation and he replied that he intended to quit the Fort of Hercules at once, taking his wife with him. This declaration left Rouletabille and myself dumb with surprise. I was the first to speak and endeavored to dissuade M. Darzac from even thinking of such an imprudence. Rouletabille frigidly inquired the reason for our friend’s sudden resolution and the latter replied by informing us of a scene which had occurred during the previous evening at the château and which revealed to us in how difficult a position the Darzacs were placed by remaining at the Fort of Hercules. The story may be summed up in a few words: Mme. Edith had had a nervous attack. We understood the reason at once for there was no doubt in the mind of either Rouletabille or myself that Mrs. Rance’s jealousy of Mme. Darzac was increasing every hour and that each act of courtesy performed by the husband toward the former object of his admiration was positively insupportable to his wife. The sounds of the fit of hysterics to which she had treated M. Rance and the words which she had spoken the night before had penetrated even through the heavy walls of “la Louve,” and M. Darzac, who was doing sentinel duty in the outer court, had been unable to help hearing some of the echoes of the young woman’s anger.

Rouletabille implored M. Darzac to endure the situation with fortitude, unpleasant as were the circumstances. He assured him that he agreed with his feeling that the stay of himself and Mme. Darzac at the Fort of Hercules must be made as brief as possible; but he also assured him that the security of both depended in great measure on their remaining in their present quarters for the time being. A new struggle had been begun between them on the one side and Larsan on the other. If they were to go away Larsan would know on the moment how to overtake them and in a time and place that they expected him the least. Here, they were forewarned, they were upon their guard, for they knew. Elsewhere, they would be at the mercy of everything and every person that surrounded them, for they would not have the ramparts of the Fort of Hercules to defend them. Certainly, this situation could not endure very long, but Rouletabille asked M. Darzac to wait eight days longer — not a single one more. “Eight days,” said Columbus long ago, “and I will give you a new world.”

“Give me eight days and I will deliver Larsan into your hands,” was not what Rouletabille said, but it was what we knew that he was thinking.

M. Darzac left us, shaking his head, doubtfully. He was angrier than we had ever seen him. Rouletabille remarked:

“Mme. Darzac will not leave us and M. Darzac will stay if she does.”

And he started off on his rounds.

A few moments later, I caught sight of Mme. Edith. She was charmingly dressed, with a simplicity which suited her marvellously. She smiled at me coquettishly, but her gayety seemed a little forced as she jested at my “new trade.” I answered her, perhaps a little too quickly, that she was uncharitable in her jests, because she knew quite well that all the trouble which we were taking and the careful watch which we were maintaining might be the means, at any moment, of saving the sweetest of women from untold misery and danger.

She looked at me mockingly and cried with a sharp little laugh:

“Oh, surely. ‘The Lady in Black!’ She has you all under her spell.”

What a ringing laugh she had! At another time, rest assured, I would not have allowed anyone to speak so lightly of “the Lady in Black,” but this morning I had not the strength of mind to assert myself. On the contrary, I laughed, too.

“Perhaps, there is a little truth in that speech,” I returned.

“My husband is crazy about her! I never would have believed that he could be so romantic. But, then,” she went on, with a droll little sigh, “I am romantic, too!”

And she turned upon me that same curious look which had disturbed me before.

“Ah?” That was all that I could find to answer.

“And, therefore,” she continued, “I take very great pleasure in the conversation of Prince Galitch, who is more romantic than all the rest of you put together.”

Whereupon I asked her who was this Prince Galitch of whom I had heard so much but had not yet seen. She told me that he was coming to luncheon — that she had invited him on our accounts; and she gave me a few particulars in regard to him from which I learned that Prince Galitch was one of the richest landholders in his own part of Russia — that portion called the “Black Lands,” fertile above all others, and situated between the forests of the North and the steppes of the Midi.

Fallen heir, at the age of twenty, to one of the greatest of Muscovite estates, he had increased his patrimony by economical and intelligent management of which no one would have believed a man so young to be capable — especially one who had heretofore had his hounds and his books as his principal objects in life. He was called a hermit, a miser and a poet. He had inherited from his father a high position at court. He was a chamberlain to His Majesty and, on account of the immense services rendered by the parent, the Emperor was supposed to regard the son with a great deal of affection. He was at once as gentle as a woman and as strong as a Turk — in brief, a thorough Russian gentleman.

I cannot tell why, but I felt a singular antipathy for the Prince without ever having set eyes on him.

His relations with the Rances were those of friendly neighborliness. Having purchased two years before the magnificent property whose hanging gardens, flowery terraces, and beautiful balconies had made it known at Garavan as “the Garden of Babylon,” he had had the opportunity to be of assistance to Edith when she had begun to make the outer court of the Château of Hercules into an exotic garden. He had presented her with certain plants which had revived, in some corners of the Fort of Hercules, a tropical vegetation hitherto scarcely known except on the banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates. M. Rance sometimes invited the Prince to dinner, and always after one of these functions the Prince would send to his hostess a wonderful palm tree from Nineveh or a cactus, fabled to have belonged to Semiramis. He declared that they cost him nothing. He had too many; he was tired of them and he did not want them among his roses. Edith said that she was interested in the young Russian because he dedicated such beautiful verses to her. After he had repeated them in Russian, he would translate them into English and he had even composed them in English for her and for her alone. Verses — the verses of a real poet, dedicated to Mme. Edith! This had so flattered her that she had requested the poet to compose English verses for her and translate them into Russian. This “literary game” greatly amused Mme. Edith, but Arthur Rance cared for it not at all. The young anthropologist did not attempt to conceal that his feelings toward Prince Galitch were not of the most friendly, and I felt assured that the traits which the husband disliked most heartily were those which the wife found most attractive in the Russian, for M. Rance had no use for “verse writing fellows,” nor did he care for those who were quite so prudent in their expenditures. He could not understand how a poet could be something very like a miser. The Prince kept no carriage nor motor car. He used the street cars and often did his own marketing, attended by his servant, Ivan, who carried a basket for the provisions. And — so said Mrs. Edith, who had heard these details from the cook — he haggled over prices with the fishwife when there was only two sous between wha

t she asked and what he offered. Strangely enough, this avariciousness did not seem in the least distasteful to Mme. Edith, who appeared to consider it a mark of originality. And, she finished by saying, “No one has ever set foot within his doors. He has never even invited us to come and see his gardens.”

“Isn’t it beautifully fascinating?” demanded the young woman when she had completed her description.

“Too beautifully fascinating!” I replied. “You will see!”

I do not know why this answer should have displeased my hostess, but I could see that it did so. Mme. Edith turned away and left me and I finished my guard duty which was an hour and a half long.

The first stroke of the luncheon bell sounded: I hurried to my room to bathe my hands and face and make a hasty toilet and I mounted the steps of “la Louve” rapidly fearing that I should be late; but I paused in the vestibule, amazed to hear the sound of music. Who, under the present circumstances, cared or dared to play a piano in the Fort of Hercules? And, hark! Someone was singing. It was a voice at once soft and sonorous singing a strange song which sounded now plaintive, now threatening! I know the song now by heart; I have often heard it since. Ah, reader, you, too, know it well, perhaps, if you have ever passed the frontiers of chill Lithuania, if you have ever entered the vast empires of the North. It is the song of the virgins who surround the traveller as he sails and destroy him without pity; it is the song that Sienkiewicz, one immortal day, made for Michel Vereszezaka. Listen.

“If you approach the Swiss lakes at the hour of nightfall, the face turned toward the lake, the stars above your head, the stars beneath your feet, and two moons shining before your eyes — you shall see this plant that caresses the bank — the wives and daughters of the Swiss whom God has changed into flowers. They balance their forms above the abyss, their heads white like the moths; their leaves are green as the needle of the maize tipped with gold.

“Images of innocence during life, they have kept their virginal robe after death; they live in the shadow and no blemish comes near them; mortal hands dare not touch them.

“The Tsar and his guard one day made the attempt when, after having gathered the beautiful flowers, they wished to wreath their brows and adorn their swords with them.

“All those who had gathered the blossoms were smitten with great ill or struck with sudden death.

“When time would have effaced these things from the memory of the people, the memory of the punishment is preserved, and in perpetuating it, the flowers are still culled the doom of the Tsars.

“Thus saying the lady of the lake departed slowly; the lake opened for her the most profound of its depths; but the eye seeks in vain for the fair unknown whose face was born out of the mist and whose voice the traveller never heard again.”

These were the words, translated into our language, of the song which was sung by the soft yet resonant voice while the piano played a weird accompaniment. I opened the door and found myself face to face with a young man who was standing. I heard the footsteps of Mme. Rance behind me and the next moment she was introducing me to Prince Galitch.

The Prince was of the type that one reads of in romances, “handsome, pensive young man”; his clear cut and rather stern profile might have given a somewhat severe expression to his face if his eyes, as mild and clear as those of a child, and with an expression of perfect candor, had not told an altogether different story. They were framed in long black lashes so black that they almost looked as though they had been touched with a pencil; and when one had noticed this peculiarity, one realized why it was that his countenance looked so strange. His skin was fresh and rosy, almost like that of a young girl. Such was my first impression of him but I felt the prejudice which I had experienced before I saw him rise up in my heart again. But it seemed to me, in spite of this, that he was too young to be of any special importance.

I could find nothing to say to this beautiful youth who chanted foreign poems. Mme. Edith smiled at my embarassment, took my arm (which gave me great satisfaction) and led me away to walk in the perfumed gardens of the outer court while we waited for the second bell for luncheon which was to be served to us in the cabin of palm trees on the platform of the Tower of the Bold.

(2) The Luncheon and What Followed — A Contagious Terror Spreads Through Our Midst.

At noon we seated ourselves at the table on the terrace of Charles the Bold, the view from which was incomparable. The palm leaves covered us with their grateful shade, for the heat of the earth and the heavens was so intense that our eyes would not have been able to endure the glare if we had not taken the precaution to put on the smoked spectacles of which I have spoken before.

Those of us at the table were M. Stangerson, Mathilde, Old Bob, M. Darzac, M. Arthur Rance, Edith, Rouletabille, Prince Galitch and myself. Rouletabille, turning his back to the sea, concerned himself very little with his companions and had placed himself in such a position that he could observe everything which transpired along the entire length of the fort. The servants were at their posts. Pere Jacques was at the entrance gate, Mattoni at the postern of the gardener, and the Berniers in the Square Tower before the door of the apartments occupied by M. and Mme. Darzac.

The first part of the meal was rather silent. I looked at the others. We were rather a solemn sight to contemplate around a table spread for good cheer — mute, and turning upon each other our dark smoked glasses behind which it was as impossible to see our eyes as to read our thoughts.

Prince Galitch was the first to make a remark. He spoke politely to Rouletabille mentioning the fame which the young reporter had won. This appeared to embarrass the lad a little and he made a confused and rather ungracious reply. The Prince did not seem to feel rebuffed, but went on to explain that he was particularly interested in the exploits of my friend for the reason that, as a subject of the Tsar, he knew that Rouletabille would shortly be sent to Russia. But the reporter replied that nothing had yet been decided and that he would prefer to say nothing on the subject until he had received his directions from his paper; whereupon, the Prince astonished us by drawing a newspaper from his pocket. It was a journal of his own country from which he translated to us a few lines announcing the fact that Rouletabille was soon to be in St. Petersburg. There was occurring in that city, the Prince went on to read to us, a series of events so strange and inexplicable in high governmental circles that, upon the advice of the Chief of the Secret Service at Paris, the Superintendent of Police had decided to ask the Epoch to lend him the young reporter. Prince Galitch had presented the affair so vividly that Rouletabille blushed to the roots of his hair as he replied dryly that he had never in the course of his short life done detective work and that the Chief of the Secret Service at Paris and the Superintendent of Police at St. Petersburg were two idiots. The Prince showed his fine teeth in a hearty laugh and it seemed to me that his laughter was not pleasant but cruel and savage. He seemed to be of Rouletabille’s opinion in regard to the Government officers, and, as if to prove the fact, he added:

“It sounds good to hear anyone talk like that, for now one expects tasks of journalists which have nothing in the world to do with their profession.”

Rouletabille made no reply and the subject was abandoned.

Mme. Edith arose from her chair, speaking ecstatically of the beauty of nature. But, in her opinion, she declared, there was nothing more beautiful anywhere near than the “Gardens of Babylon.” She added, mischievously: “They seem so much more beautiful, because one may only see them from a distance!”

The attack was so direct that it seemed as though the Prince must reply to it by an invitation. But he said nothing. Mme. Edith looked vexed and a moment later, said suddenly:

“I’m not going to deceive you any longer, Prince. I have seen your gardens.”

“Indeed! And how was that?” inquired Galitch, not losing his presence of mind for an instant.

“Yes, I have been there, and I’ll tell you all about it.”

And she r

elated while the Prince listened with an air of cold imperturbability the story of her visit to the “Gardens of Babylon.”

She had come upon them, inadvertently, from the rear, in climbing over a hillock which separated the gardens from the mountains. She had wandered from enchantment to enchantment, but without being in the least astonished. When she had walked upon the seashore, she had seen enough of the “Gardens of Babylon” to prepare her for the marvels, the secrets of which she had so audaciously stolen. She had finally reached the edge of a little pond, black as ink, upon the bank of which she saw a great water lily and a little old woman with a long, peaked chin. When they saw her the water lily and the little old woman had fled away, the latter so light on her feet in running that she fairly skimmed over the ground. Mme. Edith had laughed and had called after her:

“Madame! Madame!”

But the little old woman had seemed only more terrified and had disappeared with her lily behind the barberry hedge. Mme. Edith had continued her stroll but not quite so carelessly. Suddenly she had heard a rustle in the bushes and the strange cry which is made by wild birds when, surprised by the hunter, they escape from the prison of verdure in which they have hidden themselves. It was another little old woman, still more shriveled and wrinkled than the first, but heavier of build and who carried her cane like a battle axe. She vanished — that is to say, Edith lost sight of her in a turn of the path. And a third little old woman, leaning on two canes appeared a little further on in the mysterious garden: she escaped behind the trunk of a giant eucalyptus tree and she went so much the faster than she had done before, by running on her hands and knees so rapidly that it was amazing that she did not get all tangled up. Mme. Edith still went on. And at last she came to the marble steps of the villa with their climbing roses over head, but the three little old women were standing guard on the highest step like three rooks on a branch and they opened their threatening beaks from which escaped threatening sounds. It was then Mme. Edith’s turn to flee.

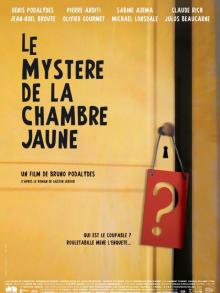

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

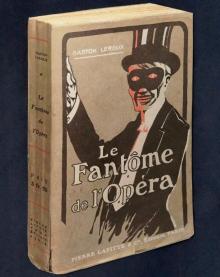

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)