- Home

- Gaston Leroux

The Bloody Doll Page 21

The Bloody Doll Read online

Page 21

This was a room in the Louis XV style. Facing the bed there was a life-size portrait of Louis-Jean-Marie-Chrysostome, who could easily be recognised in the penumbral light. As in the other rooms, the shutters were closed. Jacques walked into the room behind her. They were, without a doubt, in the room of the current Marquis. He closed the door, and suddenly Christine let out a scream.

Next to the bed, which was pressed against the wall that separated this room from the Marchioness’ chamber, a ray of sunlight appeared to pierce through the wall as it elongated its golden stave. It was the light from the next room reaching in through a hole... which they would have had difficulty in finding among the arabesques of the glass where it dissimulated itself or, on the other side, among the figures in the tapestries.

Christine ran across the room and pressed her face to the hole... and when she had finished looking:

“Now you see it!” she said to Jacques, “this is the hole through which the monster shot his poisoned arrow!”

For the first time he saw, having held the trocar in his hand, and was at last convinced: but had he not been half-convinced before? What could they do now that she was dead?

He did not pose this question to Christine, but she replied to it all the same:

“Oh, Bessie,” she declared in a low voice, “I was a bad guardian while you were alive, but I will watch over you now that you’re dead!”

XXIV

Drouine, Guardian Of The Dead

This sibylline phrase, which seemed to bind them to Coulteray for eternity, left Jacques feeling perplexed... Christine was making him feel more and more anxious: she was feverish. She was unable to remain in one place. To where could he take her now? Straight to the sacristan, who lived in a little square building made of stone, with a hole for a door and two Renaissance windows, that leaned against what remained of the ramparts and half-disappeared under the green vines and climbing plants that scaled the walls. It was a lodge from where he could guard the entrance to the chateau, a lodge that was so close to the tombs that it enabled him to watch over the dead.

Drouine was from Solognot. He was neither as quick-witted nor as impressionable as those born in Touraine and one might have believed, on becoming aware of the economy of his movements, that he lacked the ability to move. This would not be true. He worked for fifteen hours a day. Most of the time, the chateau was deserted with only Drouine in charge. The upkeep of the chapel and the cemetery occupied only a small amount of his time. He dug no more than four graves a year. He passed his time tilling the soil along the ancient ramparts on a narrow strip of land that had been bequeathed to him, on which he grew vegetables. In a word, all he did was cultivate the vines that spread wildly from the ramparts in the direction of the meadow – the Marquis, the proprietor of the land, allowed him to keep the profits he made from selling them. Archaeological visitors and tourists also helped him to line his pockets.

His dream, which was close to being realized, was to leave this marvellous land to go and bury himself in Sologne, in the savage wilderness where he was born. The only reason he had stayed was on account of the widow Gérard, to whom he had been paying a modest court for the last ten years, who had no intention whatsoever of leaving Touraine.

With the savings that all his labours had brought him he had already acquired a little property, which was waiting for them there. He had always thought that the policeman would not live for too long, because of his all-too-frequent visits to cabarets, and that his widow would not spend much time weeping for him when he was gone. He was right: the policeman used to beat her like a piece of plaster. Drouine, on the other hand, was gentle, kind and patient. She would be happy with him. She knew this.

When Christine and Jacques entered his home, he was sat at the table, bent over his bowl, looking pensive. He lifted himself up and left his morsel of bacon. With his hair like a horse’s mane, his skin like ivory, his stocky limbs, his shoulders hunched from incessant labour, he might easily have passed for a brute had it not been for his Marie-blue eyes, that twinkled with a tender honesty. At forty years old, he had preserved the look of a choirboy making his debut in the chancel.

Yet he was neither timid nor gauche. He advanced holding two chairs and asked straight away if they had seen Sangor and if they knew if he had carried out the Marquis’ orders.

“We have seen him,” said Christine, “but we have not yet spoken to him. What did the Marquis order him to do?”

“The Marquis left in a hurry!” replied Drouine, with a shake of his head, “and he did not have time to tell you that you can stay in the chateau for as long as you please – you can sleep there and you will be served as you would be if he were there. Sangor and I are at your disposal.”

“Our intention had been to return home today!” interrupted Jacques.

“But we will stay and take advantage of the Marquis’ generosity,” finished Christine.

“If you are absolutely sure you want to stay in Coulteray for a few days,” the prosector resumed, “then let’s go to the inn, where it will be more gay than installing ourselves here in this deserted chateau!”

“I didn’t come here to be gay,” said the girl, with sadness in her voice, taking Jacques’ hand as if to ask him to pardon her for her rather pointed reply, “I came here to mourn a friend.”

“Milady the Marchioness was very fond of you,” Drouine sighed.

“Tell us about her,” demanded Christine in a bass voice, “you must tell us everything: we are ready for anything... She spoke of you in all of her letters... She had the greatest confidence in you... This affair is completely out of the ordinary and we were wrong not to believe her... that wretch has deceived us all!”

“I know nothing about it!” declared Drouine.

Christine looked at him, stupefied...

“Mademoiselle, you know I have never paid much attention to the tall tales of this part of the country... I am from Sologne: down there we are all hard-headed... my mother was a servant to the priest... I served at mass from the age of seven; I believe in nothing but the catechism... This story of ‘the Empouse:’ it’s a fairy tale! Look, there’s a woman around here: she isn’t wicked, but she’s a bit of a gossip, you saw her being chased away by milord the Marquis this afternoon – the widow Gérard! Well, from time to time, maybe the widow Gérard told this story too often to milady the Marchioness whose mind, just between you and me, was never the strongest... For my part, I never contradicted her, no matter what she said. I was the only one willing to listen to her… she came crying to me, in secret, in the chapel or the sacristy... I just said to her... yes, milady... yes, milady... but I did pity her. A vampire? Have you ever seen a vampire? I’ve been the guardian of this cemetery for more than fifteen years... and, vampire or not, I’ve never seen a dead person come out of their hole once they’ve been put there! For that to happen, you’ll have to wait until the Final Judgement!”

“All of this makes good, common sense!” pronounced Jacques...

Christine turned to face him in a movement of acute hostility:

“That’s as good as maybe, but: we have the proof of the infamy of the Marquis – the proof of his crimes!” She cast a glance at him. “It’s all there and you know it, Jacques! Your attitude hurts me more than I’m able to tell you.”

“What proof?” Drouine demanded.

“Well, the hole, the hole in the wall in her bedroom – she never spoke of it to you?”

“Yes, yes! She told me about it and I’ve seen it! That hole doesn’t date from yesterday!”

“Georges-Marie-Vincent doesn’t date from yesterday either, if we are to believe the legend,” Christine let fall.

“Oh! Not that again! Have you lost your mind as well, Christine?” cried Jacques...

“And what about that pistolet you sent us? Do you know what that was for?” Christine continued, breathlessly...

“Monsieur, are you able to explain?”

“Christine, Christine!” Jacques b

egged, “be quiet, I’m begging you... be quiet! In the first place, we can’t be sure of any of this! And when the time comes to forget it, you forget,” he had taken her hands and was squeezing them with a force against which she could not defend herself, “you forget that we have another thing to do instead of occupying ourselves with the dead!”

She did not answer him, she burst into tears...

Whether it was on account of the duties of his profession, or simply out of discretion, Drouine went out at this moment, without uttering another word. Jacques attempted to calm Christine, who was becoming more nervous.

“My darling,” he said, “I agree with everything you say! The Marquis is a monster and the Marchioness a martyr. As long as we still had hope of saving her, you know I would have been the first to want you to do something! But now, I’m begging you, let’s just turn away from all of this – about which we know very little! Forget about the tragedy of Coulteray, in the same way as we have to forget about the tragedy of Corbillères! There was a time when we would not have needed all this discussion! Let’s go back to thinking only of Gabriel!”

Suddenly, she dried her tears...

“Is that what you want? Very well, it shall be as you wish,” she whispered, “but perhaps it will turn into something terrible!”

“What on earth are you talking about?”

“Ah, my dear, now you’re asking too much of me!”

“Have you decided that you want to leave?”

“Yes, calm yourself, soon we shall be in Paris.”

“But I didn’t ask you to come back to Paris straight away... for the moment, Gabriel can wait!”

“Then we’ll wait here!”

He could not restrain himself from making a gesture of impatience: to be sure, she was making a mockery of him, but he did not have time for his bad humour to manifest itself further. A singular sound came to them from outside... like someone running, like someone being pursued, accompanied by piercing little shrieks like those of a hunted bird... They went out onto the doorstep... From there they could see into a part of the cemetery that surrounded the chapel... Drouine, like a madman, was chasing from tomb to tomb, after a fleeting shadow that fled from him, whimpering, until finally it disappeared behind the chapel.

They caught up with the sacristan at the moment when he was shaking his fist at a grimacing, cackling little being that had vaulted the wall in a single bound and was now dancing a curious pirouette.

“Sing-Sing!” said Christine.

“Yes, Sing-Sing,” Drouine repeated and mopped his brow. “He never lets me have a moment’s peace... I surprised him listening outside the door... it’s that Sangor that sends him to me! I wanted to give him a good thrashing for all the strife he has caused me since they arrived here... it’s all because of that lot that milady the Marchioness became ill!”

“I’d really like to have a word with you about Sangor,” said Christine, casting a singular glance at the sacristan.

“No doubt you would,” Drouine replied: “follow me... we can talk better in the sacristy.”

When they had reached the sacristy and closed all the doors, Christine had her word. She never took her eyes off Drouine.

He seemed occupied with the arrangement of some sacerdotal robes from an old wardrobe from the 15th century which completely filled one end of the room.

“Drouine, the Marchioness had some beautiful jewels... that I know she disposed of just before she died!”

“Yes, here they are,” said Drouine, without the slightest discomfiture.

He opened the wardrobe and took out an old carved walnut coffer, which was locked. He opened it and pulled out a selection of marvellous brooches, in several designs, in filigree gold and enamel, Italian craftsmanship of the 16th Century, which would have augmented the glory of any collection. These were nothing, however, against a diadem composed of leaves of crafted gold, that was enriched with the most curious effects from blocks of coloured glass and which was fastened with two diamonds the size of small hazelnuts.

“These are the family jewels, her own property,” Christine continued, “that she sometimes showed me. It was her right to give them to whomsoever she pleased... so you can answer me without embarrassment, Drouine... the Marchioness could have given these marvellous jewels to you in the same way that she gave her pearl necklace to Sangor.”

“Indeed, she did give them to me – and here is a paper that proves it,” responded the sacristan as he pulled a document from out of the coffer.

Christine read: “I leave these jewels (a list of jewels followed) to Jean-Joseph Drouine, guardian of the chapel at Coulteray, who is charged with the duty of watching over the repose of my soul!”

“That’s all right!” said the girl as she folded the paper and passed it back to Drouine, “and now, Drouine, you can tell us how the Marchioness intended you to watch over the repose her soul!”

Drouine replaced the jewels and the paper, locked the coffer and replaced it in the wardrobe. Then he said:

“That’s my business!”

“It is mine as well, Drouine! It’s the reason I have come here! I know the last wishes of the Marchioness... I know the arrangements she made with Sangor... and she wrote to me, several days before she died, that not only had she made an arrangement with Sangor – she also came to one with you! So speak to me, Drouine. You must!”

“What do you want me to tell you?”

“I want you to tell me if the last wishes if the Marchioness have been carried out.”

“The last wishes of the Marchioness were as follows, Mademoiselle: that I should give this diadem to Sangor after she was dead!”

“And after he had cut off her head!” exclaimed Christine.

“As for the brooches,” he continued without blinking, “they are all meant for me!”

“Keep all of them, Drouine! But don’t let anyone touch the remains of my poor friend! She was tortured enough while she was alive, let her taste the sacred repose of the dead!”

“I won’t keep any of them, Mademoiselle; I’ll give them all to Sangor so that I never have to see him again! I know him all-too well! He won’t ask for more... then my poor mistress will rest in peace, intact, like an honest Christian should, in her tomb, on the honour of the name of Drouine!”

“You’re a good man, my friend!”

“Yes, Mademoiselle! But you gave me quite a fright... for a moment I believed that you, too, had come to kill the new vampire...”

“Let’s go and pray for her, Drouine!”

XXV

Midnight...

Christine wanted to spend the night in the chateau. The first floor of the north wing was put at the disposal of the two young people. They were given two bedrooms, separated by a lounge room that had, in other times, served as the private apartment of Catherine de Medici and which Louis-Jean-Marie-Chrysostome, who found the taste of those days (the days of the Pompadour) [24] particularly cheerless, had transformed and reserved for his most notable guests.

One could not tell, from their rococco stylings, that appeared brand new, if these pieces of furniture, that had once possessed a character all of their own, before being disguised with these unexpected ornamentations, presented a more cheerful or, as they had begun to say in the early years of the 19th Century, ‘more comfortable’ appearance: but it is permissible to assert that, for modern visitors, there can be nothing more dreary than all these leafy designs, these palms and laurels, crumbling into dust...all these wreaths plastered around the rose windows and on the walls of the keep...everything appears so dull, ridiculous and withered, like the rags of the drapery which seem to have been left out in the rain all day in the aftermath of a carnival.

“Oh, for the four whitewashed walls of a room at the inn,” murmured Jacques.

The idea that they would have to dine in this room, in the house of Carabosse [25], had caused such a grimace to spread over the prosector’s face that Christine ended up taking pity on him.

“Come, let’s eat a meal at the inn,” she said to Jacques, “if it would fill you with such pleasure!”

Then she added:

“You can be sure that the idea of staying here is no more amusing to me than it is to you... but I will not leave Coulteray before Sangor and you know why!... One wouldn’t know what to expect from these Hindus as soon as superstition is at stake!”

“I have every confidence in the virtue of the Marchioness’ jewels!” opined Jacques, permitting himself a wry smile. “May the Marchioness forgive us!”

On going down to the courtyard, they were pleasantly surprised to encounter Sangor and Sing-Sing, who were climbing into a torpedo car, carrying a small amount of baggage.

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

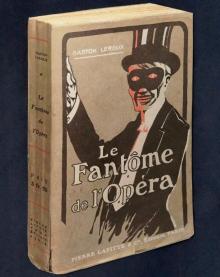

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

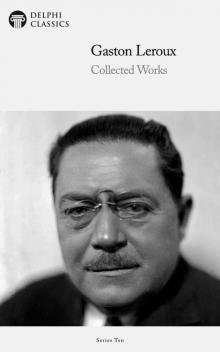

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

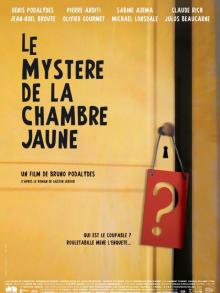

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

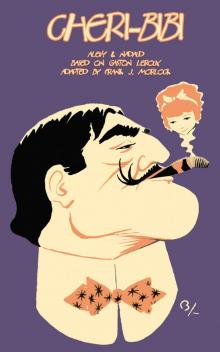

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)