- Home

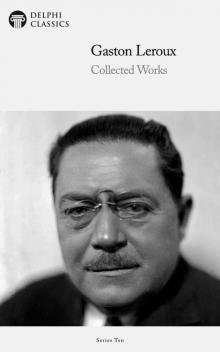

- Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Page 18

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Read online

Page 18

“That’s awful!”

“It is!”

“And what we saw her do was done to send her father to sleep?”

“Yes.”

“Then there are but two of us for to-night’s work?”

“Four; the concierge and his wife will watch at all hazards. I don’t set much value on them before — but the concierge may be useful after — if there’s to be any killing!”

“Then you think there may be?”

“If he wishes it.”

“Why haven’t you brought in Daddy Jacques? — Have you made no use of him to-day?”

“No,” replied Rouletabille sharply.

I kept silence for awhile, then, anxious to know his thoughts, I asked him point blank:

“Why not tell Arthur Rance? — He may be of great assistance to us?”

“Oh!” said Rouletabille crossly, “then you want to let everybody into Mademoiselle Stangerson’s secrets? — Come, let us go to dinner; it is time. This evening we dine in Frederic Larsan’s room, — at least, if he is not on the heels of Darzac. He sticks to him like a leech. But, anyhow, if he is not there now, I am quite sure he will be, to-night! He’s the one I am going to knock over!”

At this moment we heard a noise in the room near us.

“It must be he,” said Rouletabille.

“I forgot to ask you,” I said, “if we are to make any allusion to to-night’s business when we are with this policeman. I take it we are not. Is that so?”

“Evidently. We are going to operate alone, on our own personal account.”

“So that all the glory will be ours?”

Rouletabille laughed.

We dined with Frederic Larsan in his room. He told us he had just come in and invited us to be seated at table. We ate our dinner in the best of humours, and I had no difficulty in appreciating the feelings of certainty which both Rouletabille and Larsan felt. Rouletabille told the great Fred that I had come on a chance visit, and that he had asked me to stay and help him in the heavy batch of writing he had to get through for the “Epoque.” I was going back to Paris, he said, by the eleven o’clock train, taking his “copy,” which took a story form, recounting the principal episodes in the mysteries of the Glandier. Larsan smiled at the explanation like a man who was not fooled and politely refrains from making the slightest remark on matters which did not concern him.

With infinite precautions as to the words they used, and even as to the tones of their voices, Larsan and Rouletabille discussed, for a long time, Mr. Arthur Rance’s appearance at the chateau, and his past in America, about which they expressed a desire to know more, at any rate, so far as his relations with the Stangersons. At one time, Larsan, who appeared to me to be unwell, said, with an effort:

“I think, Monsieur Rouletabille, that we’ve not much more to do at the Glandier, and that we sha’n’t sleep here many more nights.”

“I think so, too, Monsieur Fred.”

“Then you think the conclusion of the matter has been reached?”

“I think, indeed, that we have nothing more to find out,” replied Rouletabille.

“Have you found your criminal?” asked Larsan.

“Have you?”

“Yes.”

“So have I,” said Rouletabille.

“Can it be the same man?”

“I don’t know if you have swerved from your original idea,” said the young reporter. Then he added, with emphasis: “Monsieur Darzac is an honest man!”

“Are you sure of that?” asked Larsan. “Well, I am sure he is not. So it’s a fight then?”

“Yes, it is a fight. But I shall beat you, Monsieur Frederic Larsan.”

“Youth never doubts anything,” said the great Fred laughingly, and held out his hand to me by way of conclusion.

Rouletabille’s answer came like an echo:

“Not anything!”

Suddenly Larsan, who had risen to wish us goodnight, pressed both his hands to his chest and staggered. He was obliged to lean on Rouletabille for support, and to save himself from falling.

“Oh! Oh!” he cried. “What is the matter with me? — Have I been poisoned?”

He looked at us with haggard eyes. We questioned him vainly; he did not answer us. He had sunk into an armchair and we could get not a word from him. We were extremely distressed, both on his account and on our own, for we had partaken of all the dishes he had eaten. He seemed to be out of pain; but his heavy head had fallen on his shoulder and his eyelids were tightly closed. Rouletabille bent over him, listening for the beatings of the heart.

My friend’s face, however, when he stood up, was as calm as it had been a moment before agitated.

“He is asleep,” he said.

He led me to his chamber, after closing Larsan’s room.

“The drug?” I asked. “Does Mademoiselle Stangerson wish to put everybody to sleep, to-night?”

“Perhaps,” replied Rouletabille; but I could see he was thinking of something else.

“But what about us?” I exclaimed. “How do we know that we have not been drugged?”

“Do you feel indisposed?” Rouletabille asked me coolly.

“Not in the least.”

“Do you feel any inclination to go to sleep?”

“None whatever.”

“Well, then, my friend, smoke this excellent cigar.”

And he handed me a choice Havana, one Monsieur Darzac had given him, while he lit his briarwood — his eternal briarwood.

We remained in his room until about ten o’clock without a word passing between us. Buried in an armchair Rouletabille sat and smoked steadily, his brow in thought and a far-away look in his eyes. On the stroke of ten he took off his boots and signalled to me to do the same. As we stood in our socks he said, in so low a tone that I guessed, rather than heard, the word:

“Revolver.”

I drew my revolver from my jacket pocket.

“Cock it!” he said.

I did as he directed.

Then moving towards the door of his room, he opened it with infinite precaution; it made no sound. We were in the “off-turning” gallery. Rouletabille made another sign to me which I understood to mean that I was to take up my post in the dark closet.

When I was some distance from him, he rejoined me and embraced me; and then I saw him, with the same precaution, return to his room. Astonished by his embrace, and somewhat disquieted by it, I arrived at the right gallery without difficulty, crossing the landing-place, and reaching the dark closet.

Before entering it I examined the curtain-cord of the window and found that I had only to release it from its fastening with my fingers for the curtain to fall by its own weight and hide the square of light from Rouletabille — the signal agreed upon. The sound of a footstep made me halt before Arthur Rance’s door. He was not yet in bed, then! How was it that, being in the chateau, he had not dined with Monsieur Stangerson and his daughter? I had not seen him at table with them, at the moment when we looked in.

I retired into the dark closet. I found myself perfectly situated. I could see along the whole length of the gallery. Nothing, absolutely nothing could pass there without my seeing it. But what was going to pass there? Rouletabille’s embrace came back to my mind. I argued that people don’t part from each, other in that way unless on an important or dangerous occasion. Was I then in danger?

My hand closed on the butt of my revolver and I waited. I am not a hero; but neither am I a coward.

I waited about an hour, and during all that time I saw nothing unusual. The rain, which had begun to come down strongly towards nine o’clock, had now ceased.

My friend had told me that, probably, nothing would occur before midnight or one o’clock in the morning. It was not more than half-past eleven, however, when I heard the door of Arthur Rance’s room open very slowly. The door remained open for a minute, which seemed to me a long time. As it opened into the gallery, that is to say, outwards, I could not see what was passing

in the room behind the door.

At that moment I noticed a strange sound, three times repeated, coming from the park. Ordinarily I should not have attached any more importance to it than I would to the noise of cats on the roof. But the third time, the mew was so sharp and penetrating that I remembered what I had heard about the cry of the Bete du bon Dieu. As the cry had accompanied all the events at the Glandier, I could not refrain from shuddering at the thought.

Directly afterwards I saw a man appear on the outside of the door, and close it after him. At first I could not recognise him, for his back was towards me and he was bending over a rather bulky package. When he had closed the door and picked up the package, he turned towards the dark closet, and then I saw who he was. He was the forest-keeper, the Green Man. He was wearing the same costume that he had worn when I first saw him on the road in front of the Donjon Inn. There was no doubt about his being the keeper. As the cry of the Bete du Bon Dieu came for the third time, he put down the package and went to the second window, counting from the dark closet. I dared not risk making any movement, fearing I might betray my presence.

Arriving at the window, he peered out on to the park. The night was now light, the moon showing at intervals. The Green Man raised his arms twice, making signs which I did not understand; then, leaving the window, he again took up his package and moved along the gallery towards the landing-place.

Rouletabille had instructed me to undo the curtain-cord when I saw anything. Was Rouletabille expecting this? It was not my business to question. All I had to do was obey instructions. I unfastened the window-cord; my heart beating the while as if it would burst. The man reached the landing-place, but, to my utter surprise — I had expected to see him continue to pass along the gallery — I saw him descend the stairs leading to the vestibule.

What was I to do? I looked stupidly at the heavy curtain which had shut the light from the window. The signal had been given, and I did not see Rouletabille appear at the corner of the off-turning gallery. Nobody appeared. I was exceedingly perplexed. Half an hour passed, an age to me. What was I to do now, even if I saw something? The signal once given I could not give it a second time. To venture into the gallery might upset all Rouletabille’s plans. After all, I had nothing to reproach myself for, and if something had happened that my friend had not expected he could only blame himself. Unable to be of any further assistance to him by means of a signal, I left the dark closet and, still in my socks, made my way to the “off-turning” gallery.

There was no one there. I went to the door of Rouletabille’s room and listened. I could hear nothing. I knocked gently. There was no answer. I turned the door-handle and the door opened. I entered. Rouletabille lay extended at full length on the floor.

CHAPTER XXII. The Incredible Body

I BENT IN great anxiety over the body of the reporter and had the joy to find that he was deeply sleeping, the same unhealthy sleep that I had seen fall upon Frederic Larsan. He had succumbed to the influence of the same drug that had been mixed with our food. How was it then, that I, also, had not been overcome by it? I reflected that the drug must have been put into our wine; because that would explain my condition. I never drink when eating. Naturally inclined to obesity, I am restricted to a dry diet. I shook Rouletabille, but could not succeed in waking him. This, no doubt, was the work of Mademoiselle Stangerson.

She had certainly thought it necessary to guard herself against this young man as well as her father. I recalled that the steward, in serving us, had recommended an excellent Chablis which, no doubt, had come from the professor’s table.

More than a quarter of an hour passed. I resolved, under the pressing circumstances, to resort to extreme measures. I threw a pitcher of cold water over Rouletabille’s head. He opened his eyes. I beat his face, and raised him up. I felt him stiffen in my arms and heard him murmur: “Go on, go on; but don’t make any noise.” I pinched him and shook him until he was able to stand up. We were saved!

“They sent me to sleep,” he said. “Ah! I passed an awful quarter of an hour before giving way. But it is over now. Don’t leave me.”

He had no sooner uttered those words than we were thrilled by a frightful cry that rang through the chateau, — a veritable death cry.

“Malheur!” roared Rouletabille; “we shall be too late!”

He tried to rush to the door, but he was too dazed, and fell against the wall. I was already in the gallery, revolver in hand, rushing like a madman towards Mademoiselle Stangerson’s room. The moment I arrived at the intersection of the “off-turning” gallery and the “right” gallery, I saw a figure leaving her apartment, which, in a few strides had reached the landing-place.

I was not master of myself. I fired. The report from the revolver made a deafening noise; but the man continued his flight down the stairs. I ran behind him, shouting: “Stop! — stop! or I will kill you!” As I rushed after him down the stairs, I came face to face with Arthur Rance coming from the left wing of the chateau, yelling: “What is it? What is it?” We arrived almost at the same time at the foot of the staircase. The window of the vestibule was open. We distinctly saw the form of a man running away. Instinctively we fired our revolvers in his direction. He was not more than ten paces in front of us; he staggered and we thought he was going to fall. We had sprung out of the window, but the man dashed off with renewed vigour. I was in my socks, and the American was barefooted. There being no hope of overtaking him, we fired our last cartridges at him. But he still kept on running, going along the right side of the court towards the end of the right wing of the chateau, which had no other outlet than the door of the little chamber occupied by the forest-keeper. The man, though he was evidently wounded by our bullets, was now twenty yards ahead of us. Suddenly, behind us, and above our heads, a window in the gallery opened and we heard the voice of Rouletabille crying out desperately:

“Fire, Bernier! — Fire!”

At that moment the clear moonlight night was further lit by a broad flash. By its light we saw Daddy Bernier with his gun on the threshold of the donjon door.

He had taken good aim. The shadow fell. But as it had reached the end of the right wing of the chateau, it fell on the other side of the angle of the building; that is to say, we saw it about to fall, but not the actual sinking to the ground. Bernier, Arthur Rance and myself reached the other side twenty seconds later. The shadow was lying dead at our feet.

Aroused from his lethargy by the cries and reports, Larsan opened the window of his chamber and called out to us. Rouletabille, quite awake now, joined us at the same moment, and I cried out to him:

“He is dead! — is dead!”

“So much the better,” he said. “Take him into the vestibule of the chateau.” Then as if on second thought, he said: “No! — no! Let us put him in his own room.”

Rouletabille knocked at the door. Nobody answered. Naturally, this did not surprise me.

“He is evidently not there, otherwise he would have come out,” said the reporter. “Let us carry him to the vestibule then.”

Since reaching the dead shadow, a thick cloud had covered the moon and darkened the night, so that we were unable to make out the features. Daddy Jacques, who had now joined us, helped us to carry the body into the vestibule, where we laid it down on the lower step of the stairs. On the way, I had felt my hands wet from the warm blood flowing from the wounds.

Daddy Jacques flew to the kitchen and returned with a lantern. He held it close to the face of the dead shadow, and we recognised the keeper, the man called by the landlord of the Donjon Inn the Green Man, whom, an hour earlier, I had seen come out of Arthur Rance’s chamber carrying a parcel. But what I had seen I could only tell Rouletabille later, when we were alone.

Rouletabille and Frederic Larsan experienced a cruel disappointment at the result of the night’s adventure. They could only look in consternation and stupefaction at the body of the Green Man.

Daddy Jacques showed a stupidly sorrowful face and with sill

y lamentations kept repeating that we were mistaken — the keeper could not be the assailant. We were obliged to compel him to be quiet. He could not have shown greater grief had the body been that of his own son. I noticed, while all the rest of us were more or less undressed and barefooted, that he was fully clothed.

Rouletabille had not left the body. Kneeling on the flagstones by the light of Daddy Jacques’s lantern he removed the clothes from the body and laid bare its breast. Then snatching the lantern from Daddy Jacques, he held it over the corpse and saw a gaping wound. Rising suddenly he exclaimed in a voice filled with savage irony:

“The man you believe to have been shot was killed by the stab of a knife in his heart!”

I thought Rouletabille had gone mad; but, bending over the body, I quickly satisfied myself that Rouletabille was right. Not a sign of a bullet anywhere — the wound, evidently made by a sharp blade, had penetrated the heart.

CHAPTER XXIII. The Double Scent

I HAD HARDLY recovered from the surprise into which this new discovery had plunged me, when Rouletabille touched me on the shoulder and asked me to follow him into his room.

“What are we going to do there?”

“To think the matter over.”

I confess I was in no condition for doing much thinking, nor could I understand how Rouletabille could so control himself as to be able calmly to sit down for reflection when he must have known that Mademoiselle Stangerson was at that moment almost on the point of death. But his self-control was more than I could explain. Closing the door of his room, he motioned me to a chair and, seating himself before me, took out his pipe. We sat there for some time in silence and then I fell asleep.

When I awoke it was daylight. It was eight o’clock by my watch. Rouletabille was no longer in the room. I rose to go out when the door opened and my friend re-entered. He had evidently lost no time.

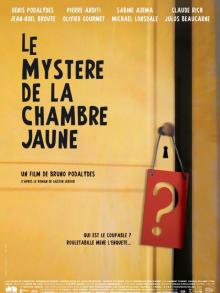

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

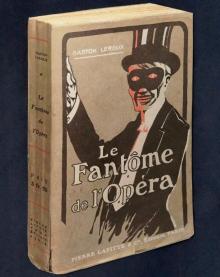

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

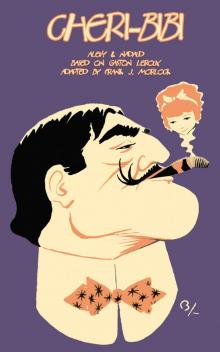

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)