- Home

- Gaston Leroux

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 13

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 13

“Fate links thee to me for ever and a day!”

The strains went through Raoul’s heart. Struggling against the charm that seemed to deprive him of all his will and all his energy and of almost all his lucidity at the moment when he needed them most, he succeeded in drawing back the curtain that hid him and he walked to where Christine stood. She herself was moving to the back of the room, the whole wall of which was occupied by a great mirror that reflected her image, but not his, for he was just behind her and entirely covered by her.

“Fate links thee to me for ever and a day!”

Christine walked toward her image in the glass and the image came toward her. The two Christines—the real one and the reflection—ended by touching; and Raoul put out his arms to clasp the two in one embrace. But, by a sort of dazzling miracle that sent him staggering, Raoul was suddenly flung back, while an icy blast swept over his face; he saw, not two, but four, eight, twenty Christines spinning round him, laughing at him and fleeing so swiftly that he could not touch one of them. At last, everything stood still again; and he saw himself in the glass. But Christine had disappeared.

He rushed up to the glass. He struck at the walls. Nobody! And meanwhile the room still echoed with a distant passionate singing:

“Fate links thee to me for ever and a day!”

Which way, which way had Christine gone? ... Which way would she return? ...

Would she return? Alas, had she not declared to him that everything was finished? And was the voice not repeating:

“Fate links thee to me for ever and a day!”

To me? To whom?

Then, worn out, beaten, empty-brained, he sat down on the chair which Christine had just left. Like her, he let his head fall into his hands. When he raised it, the tears were streaming down his young cheeks, real, heavy tears like those which jealous children shed, tears that wept for a sorrow which was in no way fanciful, but which is common to all the lovers on earth and which he expressed aloud:

“Who is this Erik?” he said.

10

FORGET THE NAME OF THE MAN’S VOICE

The day after Christine had vanished before his eyes in a sort of dazzlement that still made him doubt the evidence of his senses, M. le Vicomte de Chagny called to inquire at Mamma Valérius’. He came upon a charming picture. Christine herself was seated by the bedside of the old lady, who was sitting up against the pillows, knitting. The pink and white had returned to the young girl’s cheeks. The dark rings round her eyes had disappeared. Raoul no longer recognized the tragic face of the day before. If the veil of melancholy over those adorable features had not still appeared to the young man as the last trace of the weird drama in whose toils that mysterious child was struggling, he could have believed that Christine was not its heroine at all.

She rose, without showing any emotion, and offered him her hand. But Raoul’s stupefaction was so great that he stood there dumbfounded, without a gesture, without a word.

“Well, M. de Chagny,” exclaimed Mamma Valérius, “don’t you know our Christine? Her good genius has sent her back to us!”

“Mamma!” the girl broke in promptly, while a deep blush mantled to her eyes. “I thought, Mamma, that there was to be no more question of that! ... You know there is no such thing as the Angel of Music!”

“But, child, he gave you lessons for three months!”

“Mamma, I have promised to explain everything to you one of these days; and I hope to do so ... but you have promised me, until that day, to be silent and to ask me no more questions whatever!”

“Provided that you promised never to leave me again! But have you promised that, Christine?”

“Mamma, all this can not interest M. de Chagny.”

“On the contrary, mademoiselle,” said the young man, in a voice which he tried to make firm and brave, but which still trembled, “anything that concerns you interests me to an extent which perhaps you will one day understand. I do not deny that my surprise equals my pleasure at finding you with your adopted mother and that, after what happened between us yesterday, after what you said and what I was able to guess, I hardly expected to see you here so soon. I should be the first to delight at your return, if you were not so bent on preserving a secrecy that may be fatal to you ... and I have been your friend too long not to be alarmed, with Mme. Valérius, at a disastrous adventure which will remain dangerous so long as we have not unraveled its threads and of which you will certainly end by being the victim, Christine.”

At these words, Mamma Valérius tossed about in her bed.

“What does this mean?” she cried. “Is Christine in danger?”

“Yes, madame,” said Raoul courageously, notwithstanding the signs which Christine made to him.

“My God!” exclaimed the good, simple old woman, gasping for breath. “You must tell me everything, Christine! Why did you try to reassure me? And what danger is it, M. de Chagny?”

“An impostor is abusing her good faith.”

“Is the Angel of Music an impostor?”

“She told you herself that there is no Angel of Music.”

“But then what is it, in Heaven’s name? You will be the death of me!”

“There is a terrible mystery around us, madame, around you, around Christine, a mystery much more to be feared than any number of ghosts or genii!”

Mamma Valérius turned a terrified face to Christine, who had already run to her adopted mother and was holding her in her arms.

“Don’t believe him, Mummy, don’t believe him,” she repeated.

“Then tell me that you will never leave me again,” implored the widow.

Christine was silent and Raoul resumed.

“That is what you must promise, Christine. It is the only thing that can reassure your mother and me. We will undertake not to ask you a single question about the past, if you promise us to remain under our protection in future.”

“That is an undertaking which I have not asked of you and a promise which I refuse to make you!” said the young girl haughtily. “I am mistress of my own actions, M. de Chagny: you have no right to control them, and I will beg you to desist henceforth. As to what I have done during the last fortnight, there is only one man in the world who has the right to demand an account of me: my husband! Well, I have no husband and I never mean to marry!”

She threw out her hands to emphasize her words and Raoul turned pale, not only because of the words which he had heard, but because he had caught sight of a plain gold ring on Christine’s finger.

“You have no husband and yet you wear a wedding-ring.”

He tried to seize her hand, but she swiftly drew it back.

“That’s a present!” she said, blushing once more and vainly striving to hide her embarrassment.

“Christine! As you have no husband, that ring can only have been given by one who hopes to make you his wife! Why deceive us further? Why torture me still more? That ring is a promise; and that promise has been accepted!”

“That’s what I said!” exclaimed the old lady.

“And what did she answer, madame?”

“What I chose,” said Christine, driven to exasperation. “Don’t you think, monsieur, that this cross-examination has lasted long enough? As far as I am concerned ...”

Raoul was afraid to let her finish her speech. He interrupted her:

“I beg your pardon for speaking as I did, mademoiselle. You know the good intentions that make me meddle, just now, in matters which, you no doubt think, have nothing to do with me. But allow me to tell you what I have seen—and I have seen more than you suspect, Christine—or what I thought I saw, for, to tell you the truth, I have sometimes been inclined to doubt the evidence of my eyes.”

“Well, what did you see, sir, or think you saw?”

“I saw your ecstasy at the sound of the voice, Christine: the voice that came from the wall or the next room to yours ... yes, your ecstasy! And that is what makes me alarmed on your behalf. You are under a very

dangerous spell. And yet it seems that you are aware of the imposture, because you say today that there is no Angel of Music! In that case, Christine, why did you follow him that time? Why did you stand up, with radiant features, as though you were really hearing angels? ... Ah, it is a very dangerous voice, Christine, for I myself, when I heard it, was so much fascinated by it that you vanished before my eyes without my seeing which way you passed! Christine, Christine, in the name of Heaven, in the name of your father who is in Heaven now and who loved you so dearly and who loved me too, Christine, tell us, tell your benefactress and me, to whom does that voice belong? If you do, we will save you in spite of yourself. Come, Christine, the name of the man! The name of the man who had the audacity to put a ring on your finger!”

“M. de Chagny,” the girl declared coldly, “you shall never know!”

Thereupon, seeing the hostility with which her ward had addressed the viscount, Mamma Valérius suddenly took Christine’s part.

“And, if she does love that man, monsieur le vicomte, even then it is no business of yours!”

“Alas, madame,” Raoul humbly replied, unable to restrain his tears, “alas, I believe that Christine really does love him! ... But it is not only that which drives me to despair; for what I am not certain of, madame, is that the man whom Christine loves is worthy of her love!”

“It is for me to be the judge of that, monsieur!” said Christine, looking Raoul angrily in the face.

“When a man,” continued Raoul, “adopts such romantic methods to entice a young girl’s affections ...”

“The man must be either a villain, or the girl a fool: is that it?”

“Christine!”

“Raoul, why do you condemn a man whom you have never seen, whom no one knows and about whom you yourself know nothing?”

“Yes, Christine ... Yes ... I at least know the name that you thought to keep from me for ever ... The name of your Angel of Music, mademoiselle, is Erik!”

Christine at once betrayed herself. She turned as white as a sheet and stammered:

“Who told you?”

“You yourself!”

“How do you mean?”

“By pitying him the other night, the night of the masked ball. When you went to your dressing-room, did you not say, ‘Poor Erik?’ Well, Christine, there was a poor Raoul who overheard you.”

“This is the second time that you have listened behind the door, M. de Chagny!”

“I was not behind the door ... I was in the dressing-room, in the inner room, mademoiselle.”

“Oh, unhappy man!” moaned the girl, showing every sign of unspeakable terror. “Unhappy man! Do you want to be killed?”

“Perhaps.”

Raoul uttered this “perhaps” with so much love and despair in his voice that Christine could not keep back a sob. She took his hands and looked at him with all the pure affection of which she was capable:

“Raoul,” she said, “forget the man’s voice and do not even remember its name ... You must never try to fathom the mystery of the man’s voice.”

“Is the mystery so very terrible?”

“There is no more awful mystery on this earth. Swear to me that you will make no attempt to find out,” she insisted. “Swear to me that you will never come to my dressing-room, unless I send for you.”

“Then you promise to send for me sometimes, Christine?”

“I promise.”

“When?”

“Tomorrow.”

“Then I swear to do as you ask.”

He kissed her hands and went away, cursing Erik and resolving to be patient.

11

ABOVE THE TRAP-DOORS

The next day, he saw her at the Opera. She was still wearing the plain gold ring. She was gentle and kind to him. She talked to him of the plans which he was forming, of his future, of his career.

He told her that the date of the Polar expedition had been put forward and that he would leave France in three weeks, or a month at latest. She suggested, almost gaily, that he must look upon the voyage with delight, as a stage toward his coming fame. And when he replied that fame without love was no attraction in his eyes, she treated him as a child whose sorrows were only short-lived.

“How can you speak so lightly of such serious things?” he asked. “Perhaps we shall never see each other again! I may die during that expedition.”

“Or I,” she said simply.

She no longer smiled or jested. She seemed to be thinking of some new thing that had entered her mind for the first time. Her eyes were all aglow with it.

“What are you thinking of, Christine?”

“I am thinking that we shall not see each other again ...”

“And does that make you so radiant?”

“And that, in a month, we shall have to say goodbye for ever!”

“Unless, Christine, we pledge our faith and wait for each other for ever.”

She put her hand on his mouth.

“Hush, Raoul! ... You know there is no question of that ... And we shall never be married: that is understood!”

She seemed suddenly almost unable to contain an overpowering gaiety. She clapped her hands with childish glee. Raoul stared at her in amazement.

“But ... but,” she continued, holding out her two hands to Raoul, or rather giving them to him, as though she had suddenly resolved to make him a present of them, “but if we can not be married, we can ... we can be engaged! Nobody will know but ourselves, Raoul. There have been plenty of secret marriages: why not a secret engagement? ... We are engaged, dear, for a month! In a month, you will go away, and I can be happy at the thought of that month all my life long!”

She was enchanted with her inspiration. Then she became serious again.

“This,” she said, “is a happiness that will harm no one.”

Raoul jumped at the idea. He bowed to Christine and said:

“Mademoiselle, I have the honour to ask for your hand.”

“Why, you have both of them already, my dear betrothed! ... Oh, Raoul, how happy we shall be! ... We must play at being engaged all day long.”

It was the prettiest game in the world and they enjoyed it like the children that they were. Oh, the wonderful speeches they made to each other and the eternal vows they exchanged! They played at hearts as other children might play at ball; only, as it was really their two hearts that they flung to and fro, they had to be very, very handy to catch them, each time, without hurting them.

One day, about a week after the game began, Raoul’s heart was badly hurt and he stopped playing and uttered these wild words:

“I shan’t go to the North Pole!”

Christine, who, in her innocence, had not dreamed of such a possibility, suddenly discovered the danger of the game and reproached herself bitterly. She did not say a word in reply to Raoul’s remark and went straight home.

This happened in the afternoon, in the singer’s dressing-room, where they met every day and where they amused themselves by dining on three biscuits, two glasses of port and a bunch of violets. In the evening, she did not sing; and he did not receive his usual letter, though they had arranged to write to each other daily during that month. The next morning, he ran off to Mamma Valérius, who told him that Christine had gone away for two days. She had left at five o’clock the day before.

Raoul was distracted. He hated Mamma Valérius for giving him such news as that with such stupefying calmness. He tried to sound her, but the old lady obviously knew nothing.

Christine returned on the following day. She returned in triumph. She renewed her extraordinary success of the gala performance. Since the adventure of the “toad,” Carlotta had not been able to appear on the stage. The terror of a fresh “co-ack” filled her heart and deprived her of all her power of singing; and the theatre that had witnessed her incomprehensible disgrace had become odious to her. She contrived to cancel her contract. Daaé was offered the vacant place for the time. She received thunders of applause in th

e Juive.

The viscount, who, of course, was present, was the only one to suffer on hearing the thousand echoes of this fresh triumph; for Christine still wore her plain gold ring. A distant voice whispered in the young man’s ear:

“She is wearing the ring again tonight; and you did not give it to her. She gave her soul again tonight and did not give it to you ... If she will not tell you what she has been doing the past two days ... you must go and ask Erik!”

He ran behind the scenes and placed himself in her way. She saw him for her eyes were looking for him. She said:

“Quick! Quick! ... Come!”

And she dragged him to her dressing-room.

Raoul at once threw himself on his knees before her. He swore to her that he would go and he entreated her never again to withhold a single hour of the ideal happiness which she had promised him. She let her tears flow. They kissed like a despairing brother and sister who have been smitten with a common loss and who meet to mourn a dead parent.

Suddenly, she snatched herself from the young man’s soft and timid embrace, seemed to listen to something, and, with a quick gesture, pointed to the door. When he was on the threshold, she said, in so low a voice that the viscount guessed rather than heard her words:

“Tomorrow, my dear betrothed! And be happy, Raoul: I sang for you tonight!”

He returned the next day. But those two days of absence had broken the charm of their delightful make-believe. They looked at each other, in the dressing-room, with their sad eyes, without exchanging a word. Raoul had to restrain himself not to cry out:

“I am jealous! I am jealous! I am jealous!”

But she heard him all the same. Then she said:

“Come for a walk, dear. The air will do you good.”

Raoul thought that she would propose a stroll in the country, far from that building which he detested as a prison whose jailer he could feel walking within the walls ... the jailer Erik ... But she took him to the stage and made him sit on the wooden curb of a well, in the doubtful peace and coolness of a first scene set for the evening’s performance.

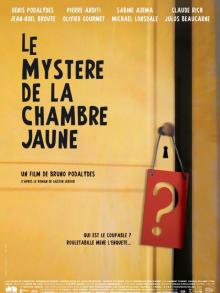

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

The Mystery of the Yellow Room The Secret of the Night

The Secret of the Night In Letters of Fire

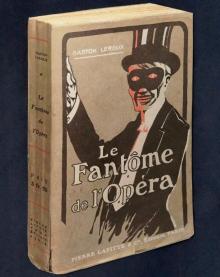

In Letters of Fire The Phantom of the Opera

The Phantom of the Opera Fantôme de l'Opéra. English

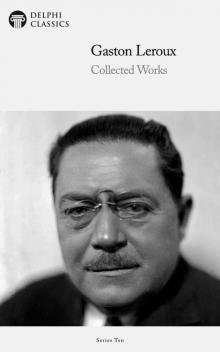

Fantôme de l'Opéra. English Collected Works of Gaston Leroux

Collected Works of Gaston Leroux Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English

Le mystère de la chambre jaune. English Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play

Cheri-Bibi: The Stage Play The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics)

The Phantom of the Opera (Oxford World's Classics) Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room

Rouletabille and the Mystery of the Yellow Room The Perfume of the Lady in Black

The Perfume of the Lady in Black The Bloody Doll

The Bloody Doll Rouletabille at Krupp's

Rouletabille at Krupp's Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Phantom of the Opera (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)